It was a large rectangular room. Chairs lined the walls. A children’s play area was tucked into a corner. One half of the room was labeled “Healthy Visits.” The other half was labeled “Sick Visits.” The check-in area was on the healthy side.

Even as a kid, this set-up made no sense to me.

Today, this set-up can be deadly.

That, along with stay-at-home orders and a myriad of other policies and practices, has propelled telemedicine to adoption and usage rates that companies like Teladoc, Doctor on Demand, and American Well could have only dreamed of 6 months ago.

But is this a new normal or will we go back to choosing a side of the large, open room in which to sit and wait?

Before we predict the path forward, let’s look at how we got here.

Telemedicine, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), generally refers to the exchange of medical information from one site to another through electronic communication to improve a patient’s health.

First commercially used in the mid-1960s by Massachusetts General Hospital to treat employees and travelers at Boston Logan International Airport[1], telemedicine as we know it today didn’t take shape until the early 2000s when high-speed internet access became more widely available.

Between Teladoc’s launch in 2005 and early 2020, adoption of the service was slow, stymied by insurance companies’ fears that easy access to physicians would increase visits without improving outcomes and therefore increase costs, medical boards’ implementation of guidelines governing how and with whom visits could occur, providers’ and patients’ beliefs that diagnosis and treatment require hands-on care, and, most importantly, lower reimbursement rates for telemedicine versus in-office visits.

Then COVID-19 happened.

- March 17: CMS announced it would:

- Reimburse office, hospital, and other visits furnished by telehealth to anyone, not just patients in rural communities, at the same rate as in-office visits

- No longer conduct audits to ensure that patients have a prior established relationship with the provider, previously defined as at least one in-person visit before using telehealth

- Waive penalties for HIPAA violations due to the use of unsecured technology, like FaceTime and Skype, assuming that health care providers were using the technologies in good faith to serve their patients

- April 3: FCC initiated $200M program, with funds coming from the CARES Act, to fund telehealth

Spurred on by these changes at the national level, throughout April, 47 state medical boards have moved to allow care to flow across state lines by waiving the requirement that the physician providing care via telemedicine channels must be licensed in the state where the patient is located at the time of treatment.

These changes created winners and losers.

With new federal and state guidelines in place, telemedicine took off.

- Cleveland Clinic went from 3400 visits per month to 60,000 in March

- NYU Langone Health went from 50 visits per day to 900 per day during the week of March 23

- Teladoc’s daily visits increased by 50% to 15,000 per day

- Austin Regional Clinic saw 50% of its visits shift to telemedicine

On April 3, Forrester released a report predicting that, by the end of the year, there would be 1B telemedicine visits compared to only 200M for general medical visits. (EDITORIAL NOTE: I don’t believe this projection one bit as it doesn’t pass the sniff test, but it is interesting in terms of highlighting the order of magnitude change that could occur)

But, as with every market shift, there are winners and losers.

Sadly, telemedicine’s gains seem to be coming at the expense of hospitals, community clinics, and rural patients.

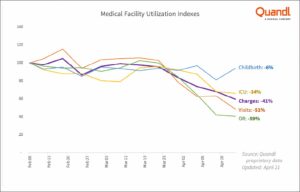

According to data from Quandl, hospital revenues dropped as much as 55% since early February as “discretionary” visits have decreased 51% while ICU and OR visits decreased 34% and 59% respectively compared to Childbirth visits (used as a control in their analysis) which only decreased 6%.

Source: Quandl proprietary data — revenue data from healthcare facilities nationwide.

Revenue and utilization decreases are hitting regional hospitals and community care centers especially hard.

- Maine hospitals are losing $250M per month

- Eisenhower Health in Rancho Mirage CA projects a $100M revenue drop

- Lifelong Medical Care in Berkeley and Oakland CA has seen a 35% drop in visits despite offering telemedicine visits

Most impacted, however, seem to be rural areas where access to high-speed internet and laptops or phones with cameras are spotty at best.

“I practice in a somewhat rural area, as do many other doctors. So half of my patients are university types and have the technology. The other half are out driving tractors, or welding, or in construction. These patients often don’t have a video capability,” Dr. Christopher Adams, a rheumatologist at East Alabama Medical Center told AL.com. In fact, he estimates that 80-85% of his patients can’t do video appointments and he received only $12 in Medicare reimbursement for a 40-minute phone visit, the same rate as a 10-min in-office visit.

Echoing this disparity is Dr. Justin Cooke, a primary care physician and co-founder of Community Urgent Care, also in Alabama. “A lot of our Medicare patients don’t have the hardware or the knowhow to participate in a video chat format for a visit.” The result? An 80% decrease in revenue since the crisis started.

This won’t last forever.

To believe that “The demand has shifted forever on virtual care, and we’re on the verge of a new era for virtual care in the healthcare system,” as Teladoc CEO Jason Gorevic proclaimed in an interview with Jim Kramer on CNBC, you need to believe:

- CMS and other insurers will continue to reimburse all currently covered telemedicine at the same rate as in-office visits

- State medical boards will continue to allow patients to have visits with doctors they haven’t seen before and/or who practice in other states

- Doctors and patients will prefer the convenience of virtual visits to the personal, hands-on experience of in-office visits

I don’t believe a single one of those things.

When CMS changed its guidelines for telemedicine in mid-March, it added 85 services to its list of covered telemedicine services. With hospitals like the Cleveland Clinic and NYU Langone Hospital reporting that 75-80% of their telemedicine visits are with people who have a cough or worried they have COVID-19, it’s hard to believe that CMS’s list of covered services will stay as long as it currently is.

State medical boards have a vested interest in supporting their constituencies, the physicians operating in their states. With some health systems strained to the breaking point by COVID-19 and others managing excess capacity, allowing physicians to operate across state lines during the crisis simply made humanitarian and political sense. But with one-third of physicians in a survey conducted by Merritt Hawkins, a physician search company, indicating that they plan to change or close their practices as a result of the pandemic, state medical boards will be motivated to act fast to protect their members and their practices.

In terms of physicians, one could argue that the current 50% adoption rate, as reported in a survey by The Physicians Foundation, means that we’ve passed the tipping point. But it’s important to remember that the jump from 18% usage in 2018 to 50% today was akin to a forced-choice rather than a voluntary one and, as a result, may not stick when circumstances change.

Convenience is often cited as a reason for patients to adopt telemedicine and it’s hard to argue with the fact that a virtual visit is faster, cheaper, and easier than a trip to the doctors’ office. But convenience matters most when you’re engaging a transaction, a functional exchange of goods or services.

Most healthcare visits aren’t transactions. What drives physician and patient behavior has less to do with functional jobs to be done (logical, rational tangible problems to be solved or progress to be made) and more to do with emotional (how I want to feel) and social (how I want others to see me) jobs. In Jobs to be Done research that I have conducted with physicians and patients over the years, I have consistently heard that the most important and satisfying part of the care experience is the personal and physical connection. Physicians say that the most gratifying moments of their jobs are when their patients hug them or shake their hands to thank them for care while patients talk about how office visits are akin to visiting lifelong friends and having conversations with people who truly know, understand, and care about them.

I also don’t believe that telemedicine will snap back to the pre-COVID normal.

I believe that some changes, like allowing physicians to treat patients across state lines or with whom they don’t have a pre-existing relationship, will revert to pre-pandemic positions. Other changes, like CMS reimbursement levels, will change based on usage data and pressure from special interest groups.

I believe that in-person connections and relationships will continue to drive physician and patient preferences. As a result, telemedicine will continue to be a more convenient version of retail clinics and urgent care, something patients use when their Jobs to be Done are purely functional (e.g. fix me, stop the pain, make me feel better) and convenience is the highest priority.

I also believe that, with the expansion of CMS covered services, the biggest change we will see is greater use in the management of chronic disease. For many patients with chronic diseases like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and even some auto-immune diseases, if their condition is properly controlled, the purpose of an office visit is to review test results and re-up prescriptions. All things that can be done more quickly, easily, and, yes, conveniently through telemedicine.

Yes, it certainly feels like we are in a “new era” of medicine.

But, when this is over, it will feel a lot more like a “new-ish” era, a variation on the theme of what came before.