by Robyn Bolton | Dec 22, 2020 | Innovation, Leadership, Strategy

“The definition of insanity is repeating the same actions over and over again and expected different results.”

This quote, often (wrongly) attributed to Albert Einstein, is a perfect description of what has been occurring in corporate innovation for the last 20+ years.

In 1997, The Innovator’s Dilemma, put fear in the hearts of executives and ignited interest and investment in innovation across industries, geographies, and disciplines. Since then, millions of articles, thousands of books, and hundreds of consultants (yes, including MileZero) have sprung forth offering help to startups and Fortune 100 companies alike.

Yet the results remain the same.

After decades of incubators, accelerators, innovation teams, corporate venture capital (CVC), growth boards, hackathons, shark tanks, strategies, processes, metrics, and futurists, the success rate of corporate innovation remains stagnant.

Stop the insanity!

I have spent my career in corporate innovation, first as part of the P&G team that launched Swiffer and Swiffer WetJet, later as a Partner at the innovation firm founded by Clayton Christensen, and now as the founder of MileZero, an innovation consulting and coaching firm.

I have engaged in and perpetuated the insanity, but I’ve also noticed something – 90% of what we do in corporate innovation speaks to our logic and reason, it’s left brain focused, and 10% speaks to creativity and imagination, our right brains. BUT 0% of our work speaks to the hearts hopes, fears, beliefs, desires, and motivations of the corporate decision-makers who ultimately determine innovation’s fate.

We spend all out time, effort, and money appealing to their brains when, in reality, the decisions are made in their hearts.

Of course, no corporate executive will ever admit to deciding with their heart, after all, good management is objective and data-based. But corporate executives are also human, and, like other humans, they make decisions with their hearts and justify it with their heads.

Consider this very common scenario:

A CEO announces to investors and employees that “Innovation” is a corporate priority and that the company will be making a “significant” investment in it over the next 3 years. A Chief Innovation Officer is put in place and Innovation Teams start popping up in every Business Unit (BU).

These BU Innovation Teams are staffed with a few people and given budgets in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. They are told to use Design Thinking and Lean Startup methods to create new products or services to better serve existing or new customers.

Each BU team, excited by their new mandate and autonomy, fan out to talk to customers, host brainstorming sessions, and create prototypes. They pull together business cases showing the huge potential of the new product or service and run experiments to prove early market traction. They meet regularly with the BU President and other key decision-makers.

Everything is going perfectly until, about a year into the work, the company has a bad quarter, or the BU is likely to miss expectations, or an innovation experiment delivers worse than expected results.

Suddenly, everyone is a skeptic. Budgets get cut. Team members are re-assigned to “help” other projects. The team’s portfolio shrinks to a single project. And like that – poof – the Innovation Team is gone.

As apocalyptic as that scenario may seem, the numbers back it up. According to research by Innovation Leader, the average tenure of a Chief Innovation Officer is 4.18 years while an Innovation Manager’s tenure is 3.3 years.

What went wrong? The company did everything by the book – they hired the right talent, established dedicated teams with dedicated budgets, talked to customers and created a portfolio of ideas, built prototypes and made small bets.

Innovation is an investment in the future so one bad quarter shouldn’t be its death knell. But it is.

The reason is that executives know that innovation must be invested in today to produce results in the future, but they do not believe that they will be rewarded for prioritizing the future over the present.

This belief then leads to fear about the uncertainty of future returns and the repercussions of failing to deliver the present, which then leads to fear that their career will stall or that they will lose their job, which then spirals into all sorts of other fears until, eventually, the executive feels forced into a “them or me” decision.

They decide with their heart (fear) and justify with their head (bad quarter).

The solution to this is neither simple nor quick but it is effective – we must dedicate as much time and effort to recognizing and addressing the thoughts, feelings, and mindsets (heart) that executives and key decision-makers face in the pursuit of corporate innovation as we spend on the structures, processes, and activities (head) of corporate innovation.

If this sounds like coaching, you’re right. It is. Just as executives benefit from coaching as they take on new and greater responsibility, they also benefit, in the form of increased confidence and better results, when they have coaches guide them through innovation. This is because innovation often requires executives to do the opposite of what they instinctively do when managing the core business.

Innovation is a head AND a heart endeavor, and we need to start approaching it as such.

To do anything less is the definition of insanity.

*** Originally published on on Forbes.com ***

by Robyn Bolton | Jul 29, 2020 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Strategy

Over the past several weeks, I’ve kicked off innovation projects with multiple clients. As usual, my clients are deeply engaged and enthusiastic, eager to learn how to finally break through the barriers their organizations erect and turn their ideas into real initiatives that generate real results.

Things were progressing smoothly during the first kick-off until a client asked, “Who’s my customer?”

I was shocked. Dumbfounded. Speechless. To me, someone who “grew up” in P&G’s famed brand management function and who has made career out of customer-driven innovation, this was the equivalent of asking, “why should I wear clothes?” The answer is so obvious that the question shouldn’t need to be asked.

Taking a deep breath, I answered the question and we moved on.

A few days later, the question was asked again. By a different client. In a different company. A few days later, it was asked a third time. By yet a different client. In yet a different company. In a completely different industry!

What was going on?!?!?

Each time I gave an answer specific to the problem we were working to solve. When pressed, I tried to give a general definition for “customer” but found that I spent more time talking about exceptions and additions to the definition rather than giving a concise, concrete, and usable answer.

That’s when it struck me – Being “customer-driven” isn’t enough. To be successful, especially in innovation, you need to focus on serving everyone involved in your solution. You need to be “stakeholder-driven.”

What is a customer?

According to Merriam-Webster, a customer is “one that purchases a commodity or service.”

Makes perfect sense. At P&G, we referred to retailers like WalMart and Kroger as “customers” because they purchased P&G’s products from the company. These retailers then sold P&G’s goods to “consumers” who used the products.

But P&G didn’t focus solely on serving its customers. Nor did it focus solely on serving its consumers. It focused on serving both because to serve only one would mean disaster for the long-term business. It focused on its stakeholders.

What is a stakeholder?

Setting aside Merriam-Webster’s first definition (which is specific to betting), the definitions of a stakeholder are “one that has a stake in an enterprise” and “one who is involved in or affected by a course of action.”

For P&G, both customers (retailers) and consumers (people) are stakeholders because they are “involved in or affected by” P&G’s actions. Additionally, shareholders and employees are stakeholders because they have a “stake in (the) enterprise.”

As a result, P&G is actually a “stakeholder-driven” company in which, as former CEO AG Lafley said in 2008, the “consumer is boss.”

How to be a stakeholder-driven organization

Focusing solely on customers is a dangerous game because it means that other stakeholders who are critical to your organization’s success may not get their needs met and, as a result, may stop supporting your work.

Instead, you need to understand, prioritize, and serve all of your stakeholders

Here’s how to do that:

- Identify ALL of your stakeholders. Think broadly, considering ALL the people inside and outside your organization who have a stake or are involved or affected by your work.

- Inside your organization: Who are the people who need to approve your work? Who will fund it? Who influences these decisions? Who will be involved in bringing your solution to life? Who will use it? Who could act as a barrier to any or all of these things?

- Outside your organization: Who will pay for your solution? Who will use your solution? Who influences these decisions? Who could act as a barrier?

- Talk to your stakeholders and understand what motivates them. For each of the people you identify by asking the above questions, take time to actually go talk to them – don’t email them, don’t send a survey, actually go have a conversation – and seek to understand they’re point of view. What are the biggest challenges they are facing? Why is this challenging? What is preventing them from solving it? What motivates them, including incentives and metrics they need to deliver against? What would get them to embrace a solution? What would cause them to reject a solution?

- Map points of agreement and difference amongst your stakeholder. Take a step back and consider all the insights from all of your stakeholders. What are the common views, priorities, incentives, or barriers? What are the disagreements or points of tension? For example, do your buyers prioritize paying a low price over delivering best-in-class performance while your users prioritize performance over price? Are there priorities or barriers that, even though they’re unique to a single stakeholder, you must address?

- Prioritize your stakeholder by answering, “Who’s the boss?” Just as AG Lafley put a clear stake in the ground when he declared that, amongst all of P&G’s stakeholders, that the consumer was boss, challenge yourself to identify the “boss” for your work. For medical device companies, perhaps “the boss” is the surgeon who uses the device and the hospital executive who has the power to approve the purchase. For a non-profit, perhaps it’s the donors who contribute a majority of the operating budget. For an intrapreneur working to improve an internal process, perhaps it’s the person who is responsible for managing the process once it’s implemented. To be clear, you don’t focus on “the boss” to the exclusion of the other stakeholders but you do prioritize serving the boss.

- Create an action plan for each stakeholder. Once you’ve spent time mapping, understanding, and prioritizing the full landscape of your stakeholder’s problems, priorities, and challenges, create a plan to address each one. Some plans may focus on the design, features, functions, manufacturing, and other elements of your solution. Some plans may focus on the timing and content of proactive communication. And some plans may simply outline how to respond to questions or a negative incident.

Yes, it’s important to understand and serve your customers. But doing so is insufficient for long-term success. Identifying, understanding, and serving all of your stakeholders is required for long-term sustainability.

Next time you start a project, don’t just ask “Who is my customer?” as “Who are my stakeholders?” The answers my surprise you. Putting those answers into action through the solutions you create and the results they produce will delight you.

Originally published on March 23, 2020 on Forbes.com

by Robyn Bolton | May 21, 2020 | Customer Centricity, Stories & Examples, Strategy

D-Day is less than 2 weeks away. On June 1, high school seniors and recent graduates will decide which, if any college to attend in the Fall. But, for most, they still won’t know where they’ll be living first semester.

Higher education, like so many other industries, has been rocked by the Coronavirus pandemic – classes are taught entirely on-line, students moved out of dorms and back home months before they planned, campuses are closed, and thousands of employees have been laid off or furloughed.

Like most other industries, colleges and universities have scrambled to respond and to prepare for what’s next. Most pushed Decision Day back a month, from May 1 to June 1, to give prospective students more time to learn about schools offering admission and to assess their own ability to pay for and attend schools when classes resume.

But colleges and universities are facing a challenge that most industries are not.

Their customers are rebelling. They are filing lawsuits. They are asking a fundamental question, “What does my tuition actually buy?”

Before the pandemic, people though they knew.

It was only 30 years ago that most high school graduates opted to go to college. According to research from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, in 1970, only 26% of middle-class workers had any post-high school education. By 1992, it had jumped to 56% and 62% in 2018.

Today, prospective students, and their families believe that a college education is the cost of entry to a middle-class life. You hear it in the Jobs to be Done (problems to be solved, goals to be achieved) they express when you ask why they want to go to college:

- “I want to get a good job when I graduate” – functional Job to be Done

- “I want to make a good living” – functional Job to be Done

- “I want to have more independence” – Emotional Job to be Done (i.e. how I want to feel)

- “I want to be part of something bigger than myself” – Social Job to be Done (i.e. how I want others to see me).

In response, colleges invested huge sums of money to convince students and their families that they offer the best solution to all of these Jobs to be Done.

- Functional Jobs to be Done:. “I want to get a good job when I graduate” and “I want to make a good living”

- Elements of the “College Solution”

- Strong reputation

- World-class education

- Renowned faculty

- Access to alumni network

- Active Career services department

- Relationships with employers

- Emotional Job to be Done: “I want to have more independence”

- Elements of the “College Solution”

- Location near a major metro area or a fun college town

- Access to student housing

- Access to food

- Social Job to be Done: “I want to be part of something bigger than myself”

- Elements of the “College Solution”

- Student clubs

- Social clubs

- Diverse student population

- Championship athletics

- Great living facilities

These elements and more are marketed in beautiful glossy brochures, recruiting roadshows, and campus tours.

The message is clear, “All of this and more could be yours if you are accepted and willing to pay.” And pay the students and their families did.

But here’s the rub.

When America went on lock-down in mid-March, colleges and universities were forced to close their campuses and send home students. Classes were moved to virtual settings with little to no training to help faculty adjust to the new format. Overnight, almost all the elements of the “College solution” disappeared or were compromised, leaving a list that looks like this:

- Functional Jobs to be Done:. “I want to get a good job when I graduate” and “I want to make a good living”

- Elements of the “College Solution”

- Strong reputation

- World-class education*

- Renowned faculty

- Access to alumni network*

- Active Career services department*

- Relationships with employers*

- Emotional Job to be Done: “I want to have more independence”

- Elements of the “College Solution” – n/a

- Social Job to be Done: “I want to be part of something bigger than myself”

- Elements of the “College Solution” – n/a

(* = significantly compromised due to moving to a virtual setting or to economic conditions)

Yet the price of the “College solution” did not change. What happens when the customer thinks they’re paying for one thing (long list of elements) and the seller gives them something less (short list of elements) and refuses to refund a portion of their money? Lawsuits. As Mark Schaffer, the parent of a George Washington University student, explained in his Washington Post Oped:

“When my daughter was deciding where to go to college, we were persuaded by George Washington University’s promises of an extraordinary on-campus experience. The school’s recruiting materials tout a dazzling array of opportunities — to engage one-on-one with renowned faculty, join more than 450 clubs and organizations, or explore passions in high-tech labs, vast libraries, and state-of-the-art study spaces.

The university promises that living at the school opens the door to “world-class” internships, lifelong friendships with neighbors and roommates, and the chance to “become a part of the nation’s capital and make a difference in it every day.” In exchange, GWU expects around $30,000 per semester. As college campuses across the country have shut down to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, most schools, including GWU, have offered only online classes since mid-March. The reason for the shift is not the schools’ fault. But this remote education is nowhere near the caliber of the on-campus experience students were promised. For this reason, I and other GWU parents have requested a partial refund of this semester’s tuition and fees. Unfortunately — and offensively — the university has refused these requests. This is why I am suing GWU for damages to compensate my family for losses suffered because of the school’s breach of contract, and why I am seeking to represent all families similarly harmed by the school through a class action.”

What happens in the Fall is unclear

As lawsuits against GWU, Northwestern, University of Chicago, NYU, Columbia, and other schools wind their ways through the legal system, everyone is scrambling to figure out what happens in the Fall. Most schools haven’t made decisions and the few schools that have seem to be falling into 3 buckets:

- Return to pre-pandemic normal by resuming all on-campus classes, activities, and operations: Brown University (as advocated by their president in a NYT Oped), Purdue University

- Proceed cautiously with a phased approach to resuming on-campus operations, classes, and living: UC Berkeley

- Stayed closed and continue virtual classes: California State University (the largest university system in the US)

Students are also struggling with their decisions. Without clarity as to what the Fall semester looks like and certainty as to their families’ financial means due to the economic downturn and rising unemployment, many students are considering taking a gap year or enrolling in a lower-cost option, such as a community college or public university.

What happens in 2021 and beyond is much easier to predict.

Certainly, the impact of decisions made about the Fall semester will reverberate for years to come as colleges cope with lost revenue from enrollment and a fairly high fixed costs base.

But the greater impact will come from students’ and families’ sudden awareness of the Mt. Holyoke Phenomenon and the role it’s played in their decision making.

First witnessed in the 1980s, the “Mt. Holyoke Phenomenon” reveals that “charging higher tuition leads to a greater number of applicants, as well as academically higher quality applicants.”

The impact of this phenomenon is simple – higher tuition attracts better students, better students demand better education and experiences, better education and experiences improve the school’s brand, a better brand means schools can raise tuition and make more money.

Given that college tuition has increased 260% since 1980, compared to the 120% increase in all consumer items, it’s reasonable to assume that, more and more, tuition is buying access to the college’s reputation.

And, as the lawsuits and declining enrollments suggest, people thought skyrocketing tuition paid for a lot more and, suddenly aware that it doesn’t, may no longer be willing to pay the premium.

The result will re-shape higher education as we know it.

Instead of getting into the most prestigious school possible and relying on financial aid and loans to pay for it, high school seniors will consider a wider variety of post-high school options, including:

- Trade schools which lead to high-paying and highly in demand skilled work

- Community colleges that grant Associate’s degrees and/or a path to transfer to a 4-year college

- Co-op programs that allow them to gain work experience at the same time as a college degree

Colleges, too, will step away from their all (on-campus) or nothing solution to offer a wider portfolio of options. In fact, some schools already have:

- Miami University has several campuses, one in Oxford offering a traditional, residential 4-year experience, and two other campuses nearby that offer part-time associates and bachelor’s degrees

- Harvard University offers a traditional 4-year college education, and undergraduate and graduate degrees through the nonresidential Harvard Extension School, and online certificates through Harvard X

- SNHU famously offers online and campus degree programs and a special “Military Experience” that offers generous tuition discounts, credit transfers, and support programs to active duty military and their spouses

It will take years for demand (what students want and are willing to pay for) and supply (what colleges and universities can offer) to reach equilibrium. But that equilibrium will look very different than it does today. Mt Holyoke taught us that in the 1980s. The coronavirus reminded us.

by Robyn Bolton | May 13, 2020 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Stories & Examples, Strategy

I took my last flight on Friday, March 13, two days after the president’s first address to the nation about COVID-19.

It was a JetBlue flight from Charlotte, NC back home to Boston. And it was awesome!

Setting aside the fact that I was wearing disposable gloves and wiping down every surface with Clorox wipes, I felt like I was flying private. I was the only person in my row, with no one in the row ahead of or behind me. Snacks and drinks were plentiful. The stewards were friendly and attentive. Even the boarding process was swift and orderly.

But when stay-at-home orders went into effect the following Monday and I shared my travel story with clients, they were aghast. How could I take such risks? Did I feel safe? Did I wear a mask?

Their reactions surprised me. After all, these executives are frequent travelers, even road warriors they travel so much. Yet the fear in their voices revealed a changing perception of travel. What was once a necessary evil for work and an efficient solution for vacation had, in just 3 days, become a senseless risk.

In the 2 months since that flight, the airline industry has been rocked. Consider:

- 94% drop in US commercial airlines’ passenger volume

- 80% decrease in US private jet flights

- 75% decrease in the number of worldwide commercial flights per day

- 80% decline in the global daily number of flight searches

- 61% increase in the amount of time between booking and traveling

That last stat – 61% increase in the amount of time between booking and traveling – indicates that people don’t expect to fly any time soon. But is that expectation a reaction to the drastic measures taken to flatten the curve or is it a sign of changing travel habits?

Many experts and industry associations are looking to data about the airline industry’s recovery post-9/11 and the 2008 global financial crisis. According to data from Airlines for America, it took 3 years for passenger volume and revenue to return to pre-9/11 levels and approximately 7 years to recover to pre-2008 financial crisis levels.

Here’s the harsh truth – we cannot possibly know what will happen next. 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis were fundamentally different events than what we’re experiencing now.

So while I understand why people are looking to these past events – data offers a sense of comfort and control over the future – using data from them is pointless. It offers a warm snuggly illusion that things won’t change that much and a return to the old days is inevitable.

Instead of looking to the past for answers, we need to look to physics.

Newton’s 3rd Law, to be precise. It states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

By looking at the actions that airlines, and regulatory and legislative bodies, are currently considering, it’s possible to predict customers’ equal and opposite reactions and, as a result, what the new normal could look like.

Photo by Nadine Shaabana on Unsplash

Action: Travelers who cross state or country borders must quarantine for 14-days unless they can prove that they are COVID-19 negative

Reaction: People will limit their travel to within their home states or countries

Most US states and many countries have 14-day mandatory quarantines in place for people traveling into their jurisdictions. Given that most trips last less than two weeks, these restrictions essentially make most travel impractical.

Some places, like Hong Kong and Vienna, are trying to lessen that barrier by testing arriving passengers at the airport and, if they test negative for COVID-19, exempting them from quarantine.

But until a vaccine is widely available, “travel is likely to return first to domestic markets with ‘staycations,’ then to a country’s nearest neighbors before expanding across regions, and then finally across continents to welcome the return of journeys to long-haul international destinations,” according to Cecilia Rodriguez, a senior contributor to Forbes.

Photo by Dino Reichmuth on Unsplash

Action: Prices increase due to fewer flights, reduced capacity

Reaction: Demand decreases as vacations become road trips and business travelers continue to use virtual meeting technology

According to research by Longwoods International, a research firm focused on the tourism industry, 82% of people traveling in the next 6 months have changed their travel plans. 22% of these people have changed from flying to driving. “Our clients are a little hesitant to get on an airplane right now,” Jessica Griscavage, director of marketing at McCabe World Travel in McLean, Virginia, told CNBC. “We’re already preparing for the drive market for the remainder of the year, and probably into 2021.”

In conversations I’ve had with business clients, the shift isn’t from air to road travel, the shift is more drastic – from traveling to not traveling. For most large companies, business hasn’t stopped or even slowed. Instead, it’s shifted to technologies like Zoom and Microsoft Teams. As people become more comfortable working “virtually,” these solutions will become far more attractive and just as effective as hopping on a plane.

Photo by CDC on Unsplash

Action: 4-hour pre-flight processing to ensure that all bags are sanitized, and all passengers are healthy

Reaction: Business travelers will choose private flights or fractional jet ownership over commercial air travel

The average business trip is approximately 3 days long according to Travel Leaders Corporate, an award-winning leader in business travel. With most days packed with meetings, executives will have neither the time nor the patience to devote half-a-day to check-in, security and health screening, and boarding.

Instead, they’ll opt for private or private-like offerings such as NetJets that offer an expedited check-in, screening, and boarding process.

Photo by JC Gellidon on Unsplash

Action: Longer flight turnarounds due to the need to sanitize planes

Reaction: Demand (and prices) for direct flights will increase while demand to get to places that don’t offer direct flights will decrease

Consultants often joke about the “Misery Tax” – the premium that clients in hard reach location have to pay to make it “worth the firm’s wile” to serve them. Although that may seem crass, there’s no debating that direct flights are significantly easier and less painful than ones that require connections.

The pain of connecting flights, however, is likely to go through the roof as the 30-minute turn-around times that airlines have been chasing become nearly impossible due to increased cleaning and sanitation guidelines. Gone will be the days when travelers worried about making their connections. Instead, they’ll worry about how to fill the hours between flights.

In fact, it’s likely that the misery of a given itinerary will shift from being a “tax” passed on to clients to a filter that business and leisure travelers will use when deciding where to travel.

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

Action: Airlines will use the need for more screening and sanitizing to justify more fees

Reaction: People will fly only when needed, instead opting for other, cheaper, and easier convenient options.

With $82B in additional revenue from add-on fees, airlines aren’t going to pull back from charging for “extras.” Instead, the need for more passenger screening, social distancing, and control over what is allowed in the cabin, will inspire even more add-on fees.

For example, airline industry consulting firm, Simplifying, predicts that airlines will no longer allow passengers to pick their seats but will instead assign seats to ensure proper social distancing and offer passengers the opportunity to pay for premium seats and/or keep the seat next to them empty.

Other options under consideration are banning carry-on baggage (which conveniently increases the number of bags checked and therefore the revenue from checked-bag fees) and selling safety kits containing face masks, disposable gloves, and cleaning wipes.

Already tired of being nickel-and-dimed, travelers are unlikely to willingly pay extra for required services and, as a result, are more likely to be open to alternatives such as car trips or virtual face-to-face meetings.

Photo by JESHOOTS.COM on Unsplash

There will always be demand for air travel.

But it may take generations for demand to pre-COVID levels.

Unlike 2001 and 2008, air travelers have options beyond commercial air carriers. Wealthy and business travelers can opt for private jets or services offering fractional ownership. Businesses, already eager to cut costs, will be more open to virtual face-to-face meetings. Families can re-discover the adventure of road trips and the creativity of staycations.

It is the availability of these comparable options combined with the invisible threat of disease that will cause people to re-think their habits and default options and slow the airline industry’s recovery. If it ever fully recovers at all.

by Robyn Bolton | Apr 28, 2020 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Strategy

It was a large rectangular room. Chairs lined the walls. A children’s play area was tucked into a corner. One half of the room was labeled “Healthy Visits.” The other half was labeled “Sick Visits.” The check-in area was on the healthy side.

Even as a kid, this set-up made no sense to me.

Today, this set-up can be deadly.

That, along with stay-at-home orders and a myriad of other policies and practices, has propelled telemedicine to adoption and usage rates that companies like Teladoc, Doctor on Demand, and American Well could have only dreamed of 6 months ago.

But is this a new normal or will we go back to choosing a side of the large, open room in which to sit and wait?

Before we predict the path forward, let’s look at how we got here.

Telemedicine, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), generally refers to the exchange of medical information from one site to another through electronic communication to improve a patient’s health.

First commercially used in the mid-1960s by Massachusetts General Hospital to treat employees and travelers at Boston Logan International Airport[1], telemedicine as we know it today didn’t take shape until the early 2000s when high-speed internet access became more widely available.

Between Teladoc’s launch in 2005 and early 2020, adoption of the service was slow, stymied by insurance companies’ fears that easy access to physicians would increase visits without improving outcomes and therefore increase costs, medical boards’ implementation of guidelines governing how and with whom visits could occur, providers’ and patients’ beliefs that diagnosis and treatment require hands-on care, and, most importantly, lower reimbursement rates for telemedicine versus in-office visits.

Then COVID-19 happened.

- March 17: CMS announced it would:

- Reimburse office, hospital, and other visits furnished by telehealth to anyone, not just patients in rural communities, at the same rate as in-office visits

- No longer conduct audits to ensure that patients have a prior established relationship with the provider, previously defined as at least one in-person visit before using telehealth

- Waive penalties for HIPAA violations due to the use of unsecured technology, like FaceTime and Skype, assuming that health care providers were using the technologies in good faith to serve their patients

- April 3: FCC initiated $200M program, with funds coming from the CARES Act, to fund telehealth

Spurred on by these changes at the national level, throughout April, 47 state medical boards have moved to allow care to flow across state lines by waiving the requirement that the physician providing care via telemedicine channels must be licensed in the state where the patient is located at the time of treatment.

These changes created winners and losers.

With new federal and state guidelines in place, telemedicine took off.

- Cleveland Clinic went from 3400 visits per month to 60,000 in March

- NYU Langone Health went from 50 visits per day to 900 per day during the week of March 23

- Teladoc’s daily visits increased by 50% to 15,000 per day

- Austin Regional Clinic saw 50% of its visits shift to telemedicine

On April 3, Forrester released a report predicting that, by the end of the year, there would be 1B telemedicine visits compared to only 200M for general medical visits. (EDITORIAL NOTE: I don’t believe this projection one bit as it doesn’t pass the sniff test, but it is interesting in terms of highlighting the order of magnitude change that could occur)

But, as with every market shift, there are winners and losers.

Sadly, telemedicine’s gains seem to be coming at the expense of hospitals, community clinics, and rural patients.

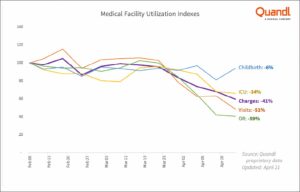

According to data from Quandl, hospital revenues dropped as much as 55% since early February as “discretionary” visits have decreased 51% while ICU and OR visits decreased 34% and 59% respectively compared to Childbirth visits (used as a control in their analysis) which only decreased 6%.

Source: Quandl proprietary data — revenue data from healthcare facilities nationwide.

Revenue and utilization decreases are hitting regional hospitals and community care centers especially hard.

Most impacted, however, seem to be rural areas where access to high-speed internet and laptops or phones with cameras are spotty at best.

“I practice in a somewhat rural area, as do many other doctors. So half of my patients are university types and have the technology. The other half are out driving tractors, or welding, or in construction. These patients often don’t have a video capability,” Dr. Christopher Adams, a rheumatologist at East Alabama Medical Center told AL.com. In fact, he estimates that 80-85% of his patients can’t do video appointments and he received only $12 in Medicare reimbursement for a 40-minute phone visit, the same rate as a 10-min in-office visit.

Echoing this disparity is Dr. Justin Cooke, a primary care physician and co-founder of Community Urgent Care, also in Alabama. “A lot of our Medicare patients don’t have the hardware or the knowhow to participate in a video chat format for a visit.” The result? An 80% decrease in revenue since the crisis started.

This won’t last forever.

To believe that “The demand has shifted forever on virtual care, and we’re on the verge of a new era for virtual care in the healthcare system,” as Teladoc CEO Jason Gorevic proclaimed in an interview with Jim Kramer on CNBC, you need to believe:

- CMS and other insurers will continue to reimburse all currently covered telemedicine at the same rate as in-office visits

- State medical boards will continue to allow patients to have visits with doctors they haven’t seen before and/or who practice in other states

- Doctors and patients will prefer the convenience of virtual visits to the personal, hands-on experience of in-office visits

I don’t believe a single one of those things.

When CMS changed its guidelines for telemedicine in mid-March, it added 85 services to its list of covered telemedicine services. With hospitals like the Cleveland Clinic and NYU Langone Hospital reporting that 75-80% of their telemedicine visits are with people who have a cough or worried they have COVID-19, it’s hard to believe that CMS’s list of covered services will stay as long as it currently is.

State medical boards have a vested interest in supporting their constituencies, the physicians operating in their states. With some health systems strained to the breaking point by COVID-19 and others managing excess capacity, allowing physicians to operate across state lines during the crisis simply made humanitarian and political sense. But with one-third of physicians in a survey conducted by Merritt Hawkins, a physician search company, indicating that they plan to change or close their practices as a result of the pandemic, state medical boards will be motivated to act fast to protect their members and their practices.

In terms of physicians, one could argue that the current 50% adoption rate, as reported in a survey by The Physicians Foundation, means that we’ve passed the tipping point. But it’s important to remember that the jump from 18% usage in 2018 to 50% today was akin to a forced-choice rather than a voluntary one and, as a result, may not stick when circumstances change.

Convenience is often cited as a reason for patients to adopt telemedicine and it’s hard to argue with the fact that a virtual visit is faster, cheaper, and easier than a trip to the doctors’ office. But convenience matters most when you’re engaging a transaction, a functional exchange of goods or services.

Most healthcare visits aren’t transactions. What drives physician and patient behavior has less to do with functional jobs to be done (logical, rational tangible problems to be solved or progress to be made) and more to do with emotional (how I want to feel) and social (how I want others to see me) jobs. In Jobs to be Done research that I have conducted with physicians and patients over the years, I have consistently heard that the most important and satisfying part of the care experience is the personal and physical connection. Physicians say that the most gratifying moments of their jobs are when their patients hug them or shake their hands to thank them for care while patients talk about how office visits are akin to visiting lifelong friends and having conversations with people who truly know, understand, and care about them.

I also don’t believe that telemedicine will snap back to the pre-COVID normal.

I believe that some changes, like allowing physicians to treat patients across state lines or with whom they don’t have a pre-existing relationship, will revert to pre-pandemic positions. Other changes, like CMS reimbursement levels, will change based on usage data and pressure from special interest groups.

I believe that in-person connections and relationships will continue to drive physician and patient preferences. As a result, telemedicine will continue to be a more convenient version of retail clinics and urgent care, something patients use when their Jobs to be Done are purely functional (e.g. fix me, stop the pain, make me feel better) and convenience is the highest priority.

I also believe that, with the expansion of CMS covered services, the biggest change we will see is greater use in the management of chronic disease. For many patients with chronic diseases like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and even some auto-immune diseases, if their condition is properly controlled, the purpose of an office visit is to review test results and re-up prescriptions. All things that can be done more quickly, easily, and, yes, conveniently through telemedicine.

Yes, it certainly feels like we are in a “new era” of medicine.

But, when this is over, it will feel a lot more like a “new-ish” era, a variation on the theme of what came before.

by Robyn Bolton | Mar 31, 2020 | Customer Centricity, Leadership, Strategy, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

It started with emails from the airlines letting us know that they’re cleaning the planes and taking precautions when handing out drinks and snacks

Then came the emails from every company you’ve ever given you email to.

Finally came the email with offers, like the one I received from a consulting firm stating that, in these uncertain times, the most important thing you can do is find new revenue streams and they can help, so give them a call.

Yes, it’s important to communicate, to be transparent about what you are doing and what you’re not doing, and to be honest about what you do and don’t know.

But that doesn’t mean that everyone needs to send an email to their customers with news, updates, and offers.

The barrage of emails reminded me of a scene from Forgetting Sarah Marshall, a frothy rom-com with a great cast and endlessly quotable quips. In this scene, the lead character, Peter (played by Jason Segal) decides to take lessons from the resort’s surfing instructor, Koonu (played by Paul Rudd).

Koonu: Okay, when we’re out there, I want you to ignore your instincts. I’m gonna be your instincts. Koonu will be your instincts. Don’t do anything. Don’t try to surf, don’t do it. The less you do, the more you do. Let’s see you pop up. Pop it up.

Peter hops up to standing on the surfboard

Koonu: That’s not it at all. Do less. Get down. Try less. Do it again. Pop up.

Peter starts to slowly do a push-up

Koonu: No, too slow. Do less. Pop up. Pop up.

Peter gets to his knees

Koonu: You’re doing too much. Do less. Pop down. Pop up now.

Peter tries again

Koonu: Stop. Get down. Get down there. Remember, don’t do anything. Nothing. Pop up.

Peter lies motionless on the surfboard

Koonu: Well, you… No, you gotta do more than that, ’cause you’re just laying right out. It looks like you’re boogie-boarding. Just do it. Feel it. Pop up.

Peter does exactly what he did the first time and hops to standing

Koonu: Yeah. That wasn’t quite it, but we’re gonna figure it out, out there.

I imagine this was the conversation that a lot of corporate/crisis communication folks were having with executives in the last two weeks — Do more. Do less. Don’t do anything. That’s not quite it.

In the midst of all of this uncertainty, how can companies know what to do now?

To be very clear, I am not an expert on communication or crisis management BUT I am an expert at understanding your customers, being a customer, and receiving lots of emails. I’m also a business owner who, for a brief moment, wondered if I needed to send a COVID-19 update to my clients and network.

Before making my decision, I asked myself these 3 questions:

Am I in a business that is the focus of a majority of the news stories? These businesses include anything in travel (airlines, cruises, hotels), food and food service (restaurants, fast food, grocery), medical supplies (masks, gowns, gloves, ventilators).

If the answer is YES, send an email because people are thinking about you and wondering what you’re doing to keep them safe.

My answer was NO, so I went to the next question.

Am I a business that is woven into people’s daily lives? These could be essential businesses like banks, medical professionals (dentists, orthodontists, chiropractors), and cleaning services (home cleaners, dry cleaners, laundromats). The list could also include non-essential businesses like personal service providers (hair stylists, nail techs, aestheticians).

If you are a steady part of people’s lives, then YES, you should send them an email to let them know what you’re doing in light of the situation.

I’m a part of most of my clients’ lives during projects which have start and end dates, so I went to the next question.

Am I making fundamental changes to my business that will directly and immediately impact my customers? These changes could include changing your hours of operation (e.g. adding Senior hours), changing how you transact business (e.g. no more curb-side pick-up). Or the changes could be bigger, like closing because of a government order, or delaying or even cancelling shipments because manufacturing and shipping processes are delayed due lack of materials or staff.

If you’re making a fundamental change to how you do business, you should let your customers know and help them reset expectations.

Other than moving all meetings to Zoom and no longer traveling, no element of my business operations changed.

DECISION: Do less.

I did not send a “How MileZero is responding to the Coronavirus” email because, based on the answers to the three questions above, my clients had far more pressing concerns than how often I’m using Clorox wipes to clean my keyboard.

But I didn’t do Nothing.

In the work I do with clients, I get to know them extremely well. We move from the typical consultant-client interaction to a trusting (professional) relationship between two human-beings.

What I did tried to reflect that.

I sent quick personal notes to each individual, wishing them health and safety, asking how they and their families are doing, and offering to hop on the phone for a quick chat, to be a sounding board, or simply a shoulder to lean on. It’s not much but it’s genuine and appropriate for the circumstances.

I did not try to tell them what they should be doing right now. Nor did I try to sell them a new service. I simply offered support and connection because, in a time of social distancing, connection is what we need right now.

What do we do now?

The same thing we should have been doing all along. We think of our customers (i.e. the people at the other end of the email) and what they want and need, and we do our best to serve them.

Sometimes we’ll get it right. Sometimes we’ll get it wrong. But if we think first of our customer, not ourselves or our businesses, we’re gonna figure it out.

Just like Koonu promised.