by Robyn Bolton | Aug 28, 2021 | Innovation, Leadership

I do. We do. You do.

My Mom taught pre-school. It wasn’t a job; it was her calling. Kids gravitated to her like she was the Pied Piper, and she greeted them with unequaled patience, acceptance, and love. Years later, her students would talk about how she changed their lives when they were only four years old. And she did it by following one simple rule.

I do. We do. You do.

Whatever she was teaching, whether it was sitting still at a table and eating a snack or writing the alphabet, she always did it first so the kids would know that it’s possible and not be afraid to try.

Then, they would do the activity together. Side-by-side, they would eat a snack or draw letters, the kids occasionally glancing to the side to mimic her and my Mom gently coaching and encouraging.

Finally, she would step back, never disappearing completely, always within sight, but no longer right there. By doing this, she created the space for them to be independent and to build confidence.

It is easy to say that she was teaching.

It is more accurate to say that she was leading.

It is precisely what executives need to do if they want to build a culture and capability of innovation within their teams and businesses.

I do.

It is not enough to encourage your team to take risks. YOU need to take risks. Ask a question in a meeting. Say, “I don’t know.” Challenge the status quo. Be the first to do something different or uncertain, so your people know that it’s possible and aren’t afraid to try.

We do.

Don’t sit back in judgment, demanding that your teams present their work to you, and bombarding them with questions that begin with, “Did you think about…?” or demands for data that couldn’t possibly exist.

Instead, coach them and encourage them. Sit next to them as they share the work they’ve done and ask questions to learn more. Work with them as they think through options and examine alternatives.

You do.

It’s tempting to want to stay in the work and continue exploring and creating, but you eventually need to step back and let the team work. Give them the time and space to make progress without constant updates. Give them the resources to do bigger and better things. Give them more independence so they can build their confidence and a track record of success.

But don’t disappear. Be close enough that when the team needs you, you’re just a shout away. Most importantly, actively advocate for and defend the team when the cultural antibodies hell-bent on defending the status quo arrive and begin their attack.

I do We do You do is what leadership looks like.

Whether you’re learning the alphabet or innovating within a big company.

by Robyn Bolton | Aug 25, 2021 | Innovation, Strategy

Most people know that 95% of new products fail within three years of launch. It’s often cited as evidence of big companies’ inability to be innovative, keep up with changing consumer demands, and respond to the nimbleness of start-ups.

Naturally, companies don’t want to fail in the market, so they try to get better at listening and responding to customers, more comfortable investing in unproven but potentially market-defining technology, and more willing to question and change their business models.

Yet, the market failure rate stays essentially the same.

“Ah-ha!” the experts proclaim, “if companies are doing everything right and 95% of innovation projects are still failing, that means that projects are launching that shouldn’t be. That means we must get better at killing projects before they launch!”

Suddenly, Fail Fast becomes the corporate mantra. More projects start because it’s ok to fail. More projects get killed, a mind-boggling 99.9%, according to one study. Fewer projects get launched.

Yet, the market failure rate stays essentially the same.

Why? Why does the market failure rate stick stubbornly at 95% if companies are doing all the right things, including killing 99.9% of ideas and projects before they even get to market?

Because it’s not enough to do the right things.

You must do the right things in the right ways at the right times.

Here are the three most important ones:

Right Thing #1: Start with a problem

All successful innovators know that successful innovations create value because they solve problems for people willing to pay for the solution. This is why I constantly advise my clients to “fall in love with the problem, not the solution.”

Right Way: Finding a problem that people are willing to pay to solve isn’t enough. Companies need to find and invest in problems that align with their priorities and strategies, not just the passions of their innovation teams, R&D department, or top performers.

Right Time: If a problem does not align with a company’s priorities or strategy, kill it before it even becomes a project. Don’t say, “let’s explore this further. Maybe there’s something there,” or “let’s get something the market and see what happens.” When the company set its strategies, it made choices about what it does and does not do, which means that before the problem was even found, the company chose to kill work on it. Respect that choice and focus scarce resources on problems and projects that support the company.

Right Thing #2: Listen to consumers

“The consumer is boss,” former P&G CEO and Chairman AG Lafley once said. He’s right. If the consumer doesn’t have a problem, doesn’t like the solution you’re offering, or isn’t willing to pay what you want for the solution you designed, then failure is inevitable. Innovation begins and ends with the consumer.

Right Way: LISTEN, don’t talk to consumers. Lots of companies talk to consumers – they tell consumers what they’re creating and ask for feedback, what other companies are doing and ask for critiques, what consumers should want and what they should do, and then ask for money in return. Listening means asking open-ended questions, letting consumers think and respond, and believing and acting on the answer, even if it’s not the answer you want.

Right Time: Always. Constantly. Forever. It’s not enough to listen to consumers at the beginning when searching for a problem to solve or in the early days of designing a solution. Listen to them during prototyping, during the MVP stage, before launch, after launch, and every single day after that.

Right Things #3: Learn fast

F*ck fail fast. Failure sucks. No one wants to fail, no matter the speed. It’s not ok to fail because it means that you made an avoidable mistake, made a decision despite the data, and took an unnecessary risk.

But learning is entirely different. When you make a mistake, you learn, which prevents you and others from making the same mistake. When an experiment results in an unexpected outcome, you make new connections between pieces of data, and that learning opens new possibilities and closes down false ones. When you weigh the data, take a calculated risk, and it doesn’t work out, you learn that chance and luck play a role in business.

Right Way: Be honest about what you don’t know, what you need to know, and what you will do once you know. In the long run, false confidence serves no one and, more often than not, leads to very expensive and very public failures. Make the implicit explicit, state your assumptions, and pursue a learning plan, NOT a launch plan.

Right Time: Early and often. Lean start-up and Agile methodologies encourage companies to surface and test assumptions starting with MVPs because it’s when the costs of progress and failure begin to become materials. But uncertainty exists right from the start. The moment a problem is found, assumptions are made about the market’s attractiveness, a solution’s feasibility and viability, and the willingness of the company to invest. Write them down, share them with key decision-makers, test them through small and scrappy experiments. Start learning from day 1 so you don’t fail at day 1,000.

100% success shouldn’t be the goal. Neither should 5%.

Entrepreneurs and innovation experts will admonish companies that, if they succeed 100% of the time, they’re not taking enough risks and truly innovating. While that’s true, there’s also a lot of space between the current 95% failure rate and the inadvisable 0% failure rate.

Doing the right things – starting with a problem, listening to consumers, and learning fast – but companies need to do the right things, in the right ways, at the right times, to be successful more than 5% of the time.

by Robyn Bolton | Jul 15, 2021 | Innovation

“How might we ruin a perfectly good and useful tool?”

This might not be the question that innovators, design thinkers, and brainstorm facilitators wanted to answer. But it seems that it’s the one they did.

“The most popular design thinking strategy is BS,” proclaimed the headline on a June 28 article in Fast Company. “The ‘How might we’ design prompt is insidious, and it’s time to bury it.”

I’m a sucker for provocative headlines, especially ones that challenge that status quo, so I clicked and read the article. And I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it.

The reason “How might we” (HMW) is so insidious, the author asserts, is that

The “we” in HMW refers to the people in the room, not to the users, customers, or populations for whom teams are designing their products and services. The prompt looks inward instead of outward, encouraging people to build solutions that suit their own needs and experiences. They end up with offerings that don’t serve customer needs and may even hurt the people they’re meant to help.

The problem (and solution) of “We”

OK. Fair. As I recounted in last week’s episode of “What Matters in Innovation,” I saw this exact worry come to life when I was an Assistant Brand Manager on Swiffer WetJet. While the brainstorming promotional ideas as a brand team, the most senior member suggested a Valentine’s Day promotion encouraging men to buy a WetJet, then priced at $50, for their wives “because she’s worth it.” Everyone in the room nodded in silent awe and acceptance, except one person. Me. The only woman in the room.

Once I picked my jaw off the floor, I expressed concerns about the promotion, but they were brushed aside because “what woman wouldn’t want help cleaning the floor.” Instead of explaining the help that women wanted was probably more akin to a maid or the man doing the chores, I asked my boss to call his wife and get her opinion. He made the call, put her on speakerphone, and explained the situation.

“Would you please take me off speakerphone?”

He did but it wasn’t necessary. Her furious exclamations were easily overheard.

He put the phone down and the idea was never again discussed.

But as much as that story illustrates the problem of the “We,” it also demonstrates the solution – talk to your customers!

“We” is exactly who should be dreaming up a solution. After all, if a company is going to create a solution to a customer problem, the people coming up with the solution need to know if it’s something the company can and will do.

The problem doesn’t occur when “We” come up with a solution. The problem occurs when the design and development process stops with “We” instead of continuing back outside the conference room walls to see what “They” (our customers) think of what “We” created.

The solution (and problem) of “How might”

The article gives a brief and fascinating history of HMW, busting the myth that it started with IDEO by sharing stories from its first use at P&G:

In the early 1970s, business consultant Min Basadur helped steer an internal P&G product development team toward broader thinking through an HMW-driven discussion. By shifting the team’s focus away from competing products and encouraging them to consider more ambitious questions, he got them to be wildly creative while simultaneously leveraging P&G’s innate strengths.

“Wildly creative.”

I’ve been in hundreds of ideation sessions, including ones at some of the most creative companies in the world, and I can’t think of one that could be described as “wildly creative.”

40+ years ago, “Might” might have been novel enough to encourage people to be creative, to prompt wild ideas, and to risk sounding silly in the “safe space” of a brainstorming session. But not today.

Today, we’ve heard “How might we” so many times that we’ve stopped listening. Instead, we hear “How should we” or “How can we” or “How will we.” The pace of business is so fast and the work on our plates is piled so high that we don’t have the time or mental space to go beyond To Do and wonder what we might do.

The problem (and solution) at the end of “How might we”

What makes HMW BS isn’t “How might” or “We” it’s what comes after those words. It’s how we finish the sentence.

Sentence finisher problem #1

Once IDEO spread the gospel of design thinking and popularized HMW, they encouraged people to use it as a tool to solve “’wicked problems’ – problems that are so complex there is no right or wrong answer.”

Here’s the problem with that – “wicked problems” are things like racism, social inequality, economic inequality, food insecurity, gender discrimination. “Wicked problems” are not things that can be solved in a brainstorming session.

Sentence finisher problem #2

Far more common, in my experience, isn’t the use of HMW to solve wicked problems but rather to brainstorm solutions to customer problems.

At least, that’s what people say.

More often, HMW is used to brainstorm solutions to the company’s problem dressed up to look like a customer problem.

Consider this HMW prompt from a recent brainstorming session I was invited to:

“How might we decrease costs by getting more customers to use our self-service options?”

Luckily, the whole session fell apart quickly when I asked, “Do we know why customers aren’t using your self-service options now?” and the room fell into an awkward silence. If you don’t understand the problem, you can’t create a solution.

HMW is not BS. How we use it is.

If we use it as an excuse to stop talking to customers, that is our mistake, not a flaw with the tool.

If we stop hearing “might” and stay anchored in should, can, and will, that is our mistake, not a shortcoming of the tool.

If we use it to solve massively complex and arguable unsolvable problems because we’re too lazy to dig deeper, tease out the hundreds of root causes, and attack them one by one, that is our mistake, not the tool’s limitation

If we pretend that our solution is the customer’s problem, that’s our failure, not the tool’s,

After all, a good craftsperson never blames their tools.

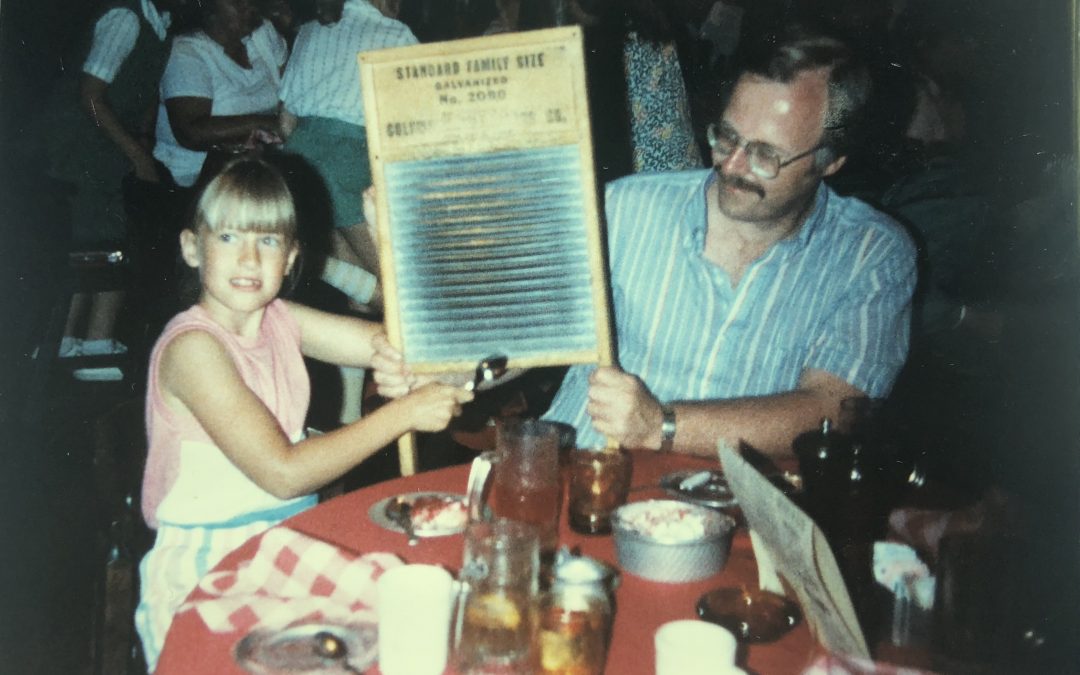

by Robyn Bolton | Jun 17, 2021 | Innovation, Stories & Examples, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

Innovation is all about embracing the AND.

- Creativity AND Analysis

- Imagination AND Practicality

- Envisioned Future AND Lived Reality

Looking back, I realize that much of my childhood was also about embracing the AND.

- Mom AND Dad

- Nursery School Teacher AND Computer Engineer

- Finger paint AND Calculus

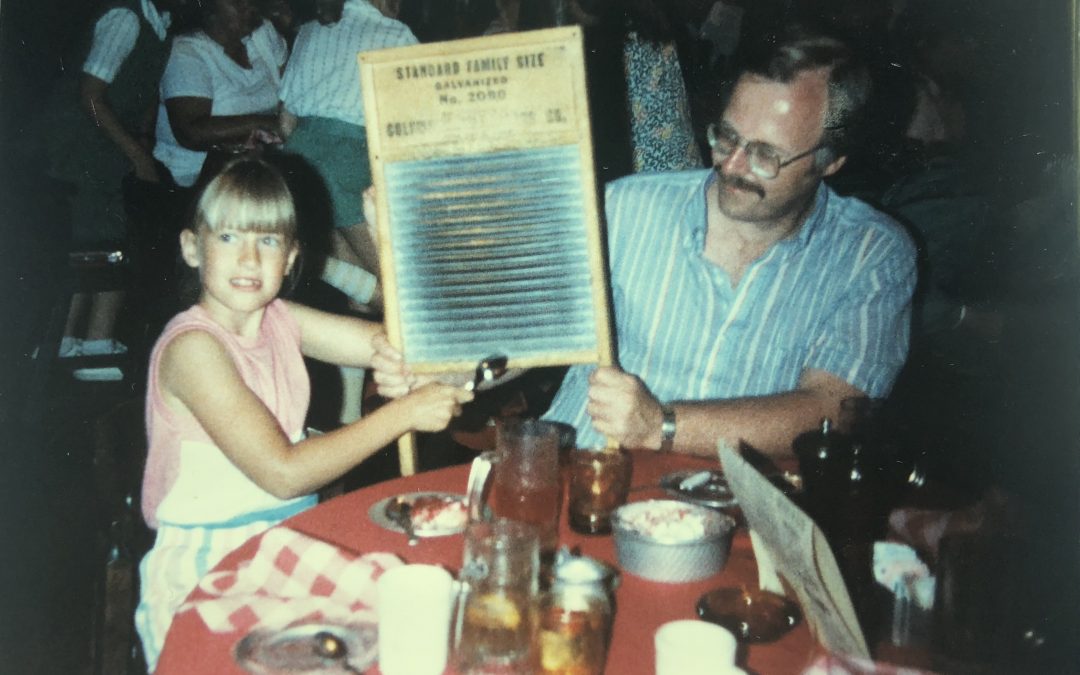

A few years ago, I wrote about my mom, the OG (Original Gangster) of Innovation. She was what most people imagine of an “innovator” – creative, curious, deeply empathetic, and more focused on what could be than what actually is.

With Father’s Day approaching, I’ve also been thinking about my dad, and how he is the essential other-side of innovation – analytical, practical, thoughtful, and more focused on what should be than what actually is.

In the spirit of Father’s Day, here are three of the biggest lessons I learned from Dad, the unexpected innovator

Managers would rather live with a problem they understand than a solution they don’t.

When Dad dropped this truth bomb one night during dinner a few years ago, my head nearly exploded. Like him, I always believed that if you can fix a problem, you should. And, if you can fix a problem and you don’t, then you’re either lazy, not very smart, or something far worse. Not the most charitable view of things but perhaps the most logical.

But this changed things.

If you’ve lived with a problem long enough, you’re used to it. You’ve developed workarounds, and you know what to expect. In a world of uncertainty, it is something that is known. It’s comfortable

Fixing a problem requires change and change is not comfortable. Very few people are willing to sacrifice comfort and certainty for the promise of something better.

What this means for innovators is that it is not enough to identify, understand, and convince people of a problem. In order to make progress, we need to also identify, understand, and convince people that the solution is a better option. When people agree there is a problem but refuse our solution, it’s not because they’re lazy, dumb, or something worse. It’s because we haven’t given them a solution they understand. We have more work to do.

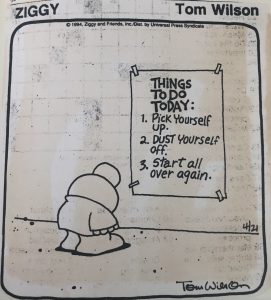

Pick Yourself up.

Dust yourself off.

Start all over again

My dad had an office job doing office stuff. We never really knew what he did, to the point that when True Lies came out, we (my mom, sister, and I) just started telling people that he was a spy.

Like everyone who has office jobs doing office things, Dad had lots of meetings and projects which means he also had some frustrating days. As I stepped out into the world, he knew I would have some frustrating days, too. So he gave me this Ziggy cartoon with a little note: “Keep things in perspective – it’s always a new day and a new opportunity for a fresh start.”

Not an easy thing for an impatient perfectionist to remember.

And isn’t that what innovators are? We’re impatient, we believe things can (and should) be better, and we don’t always react that well when other people don’t see what we believe is blindingly obvious. Sometimes we handle it well but sometimes we fall down (lose our tempers, yell at people, etc.).

Innovation, especially innovation within an existing company is hard. We will fall down because we’re trying to do something that’s really hard, drive change. But we can’t stay down. We need to pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and try again.

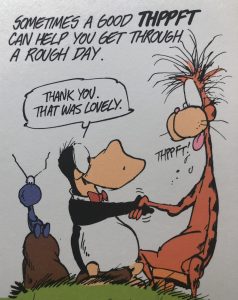

Sometimes a good THPPFT can help you get through a rough day

Mom was the silly one. Dad was the serious one. So it was a bit surprising when I received this card from Dad a few days before Finals.

He was right.

It’s important to remember that a good THPPFT, or burst of laughter, or *&%$#, or 30-second dance party can get you through a rough day. It breaks up the intensity and the self-imposed seriousness of whatever is happening.

Innovation, especially Design Thinking, is rooted in child-like wonder – curiosity, creativity, surprise, and joy. As innovators, if we get mired in the seriousness and stress of work, we will lose the joy and humor required to create and change. We need a good THPPFT to stay effective innovators.

One final nugget

In previous blog, I’ve mentioned a poem that Dad gave me, probably in HS, that I think about regularly. I am quite sure that there were times he deeply regretted sharing this with his head-strong, opinionated, and slightly anti-authoritarian daughter, as evidenced by the hand-written note on the paper version – “don’t think you’ll always be right.”

While I was right that I would never use calculus (or physics or chemistry) after school, he was right to share this with me. And now I share it with you:

Will The Real You Please Stand Up?

Submit to pressure from your peers and you move down to their level.

Speak up for your own beliefs and you invite them up to your level.

If you move with the crowd, you’ll get to further than the crowd.

When 40 million people believe in a dumb idea, it’s still a dumb idea.

Simply swimming with the tide leaves you nowhere.

So if you believe in something that is good, honest, and bright –

stand up for it.

Maybe your peers will get smart and drift your way.

– Edward Sanford Martin

by Robyn Bolton | Apr 7, 2021 | Innovation, Just for Fun, Stories & Examples

A few weeks ago, I wrote a post using quotes from “Moneyball” (the movie, not the book) to describe the experience of trying to innovate within a corporate setting.

It was great fun to write, I received tons of feedback, and had many fascinating conversations (plus a fact check on the year the Red Sox broke the Curse of the Bambino), so I started searching for other movies that inadvertently but accurately describe the journey of corporate innovators.

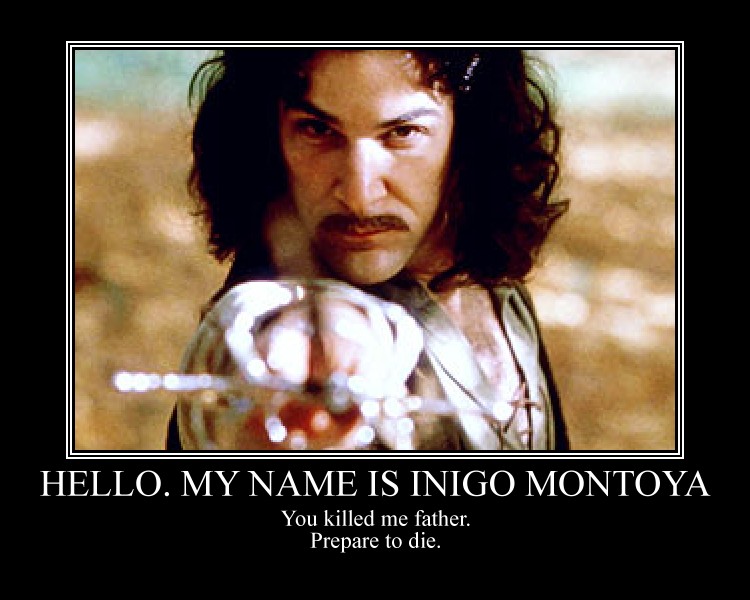

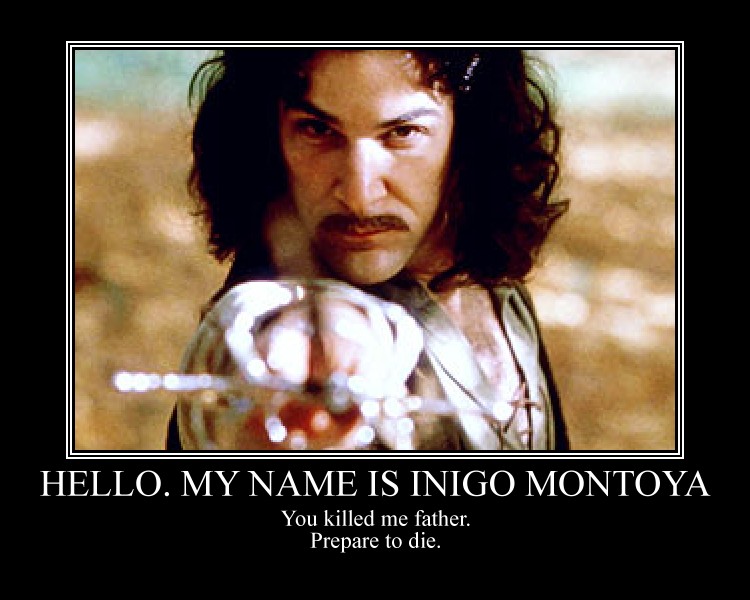

The Princess Bride

If you have not seen The Princess Bride, stop reading and immediately go watch it. Seriously, there is nothing more important for you to do right now than to crawl out from the cultural rock you’ve been under since 1987 and watch this movie.

If you’re reading this, you’ve clearly watched the movie and know that it is packed with life lessons and quotable quotes. It also captures the reality of innovation within the walls of large companies

The Beginning

“You keep using that word. I don’t think it means what you think it means.” – Inigo Montoya

A company’s focus on Innovation usually begins the moment a senior executive, usually the CEO, declares it to be a key strategic priority and promises Wall Street analysts that significant investments will be made.

It then trickles down to business units and functions, with each subsequent layer told to “be more innovative” and “come up with more innovation.”

Then, one day, the responsibility for innovation lands in someone’s lap and stays there. To be honest, it’s usually an exciting day for the person because they’ve been asking questions, suggesting ideas, and pushing for innovation for a long time, and now the powers that be have permitted them to do something about it. They may even have been given a title and budget specific for innovation.

But “innovation” was never defined.

The CEO may think it is an entirely new business, something flashy and new that rivals anything coming out of Silicon Valley.

The Business Unit and Functional Heads may think it’s a new product or technology, something just different enough from the current business to be newsworthy but not so different that it changes how things are done.

And the new Innovation owner thinks it’s new ideas, lots of brainstorming sessions, and networking with entrepreneurs and startups.

Without alignment as to what “innovation” means and what it needs to deliver, the stage is set for misalignment, frustration, and ultimately failure. Al because that word, “Innovation,” does not mean what you think it means.

The Middle

“We’ll never survive.” – Buttercup, the Princess Bride

“Nonsense, you’re only saying that because nobody ever has.” – Westley

Let’s imagine for a moment that a common definition and set of expectations for innovation is established and everyone up and down the corporate hierarchy is in agreement (this actually does happen, but it takes effort).

The innovation owner has a clear mandate and is hard at work building an innovation pipeline – they’re having lots of qualitative interviews to build customer empathy, they’re facilitating brainstorming sessions to get ideas, they’re building prototypes to get customer feedback. Most importantly, they’re sharing their work with anyone who will listen, asking for feedback, and building supporters and champions.

And then, the chorus begins.

“This will never work”

“You’ll never get approval for that”

“If we do that, we’ll lose customers”

“If you do that, you’ll be fired.”

In these moments, the dark seeds of doubt are planted. The innovation owner must dig deep, reminding themselves that people are only saying those things because it hasn’t worked yet, no one got approval yet, customers haven’t yet weighed in, and you haven’t tried to do that yet.

After all, just because something has never been done, doesn’t mean that it can’t be done.

The End

“Thank you so much for bringing up such a painful subject. While you’re at it, why don’t you give me a nice paper cut and pour lemon juice on it.” – Buttercup, the Princess Bride

Let’s be honest, most corporate innovation efforts don’t result in the world-changing, life-affirming successes we hop for. Innovators are, by nature and necessity, an optimistic bunch so when things don’t work out as we hope, it hurts. It hurts as much as a paper cut with lemon juice poured on it.

But there is one truth that cuts across all attempts at corporate innovation, no matter whether the journey ends with wild success in the form of massive business growth, happy success in the form of new products and revenue streams, satisfying success in the form of improvements and greater efficiencies, or bitter disappointment because nothing changes and everyone goes on to old or new jobs.

“I supposed you think you’re brave, don’t you?” – Vizzini

“Only compared to some.” – Buttercup, the Princess Bride

Those who took on the work and responsibility of innovation are brave.

Not only compared to some but compared to most.

It takes guts to try something new. To ask questions. To challenge the status quo. To continue seeking a yes amongst a thousand no’s. To put your reputation, your bonus, and maybe even your job on the line.

And that’s what corporate innovators need to remember – that whatever happens, they were brave. They worked hard, they battled the odds, they did make change happen. Even if it was only how they see and understand the world. Even if it only to get smarter and stronger and prepare for the next time they are called upon to drive change.

Because in that moment, innovators must be ready to say “As you wish.”

by Robyn Bolton | Apr 1, 2021 | Innovation, Metrics

Of all the facets of innovation, innovation metrics may be the most requested, studied, and debated.

This is not surprising given that companies need to justify the billions of dollars they spend every year on “innovation” and the best way to do that is through a sound set of metrics with proven predictive power and relevant benchmarks.

However, despite the need, and decades of work to address it, a satisfying answer to “what innovation metrics should we use?” is as elusive as ever.

The key word there is “satisfying”

Innovation metrics exist. There are probably hundreds of them.

Innovation metrics are in use. Maybe even at your company.

But one universal set of metrics with proven predictive power and relevant benchmarks? Nope, that doesn’t exist.

And it shouldn’t exist.

What innovation is, why it is pursued, and the investment of resources and time required varies from industry to industry and company to company. So, it makes no sense to apply a standard set of metrics to a custom approach and activity.

The trap of “satisfying” metrics

“What gets measured gets managed” is a trap (and also not true and Peter Drucker never said it).

It’s a trap because, as noted by monetary theorist Charles Goodhart noted, “Any statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.”

Or as us common folk (and anthropologist Marilyn Strathern) say, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

It is not satisfying when ideas become cobras

Although Goodhart’s Law was first articulated in 1975, it’s been in action for centuries. Consider the story of the British government’s bounty on cobras back when India was still a colony – to reduce the cobra population, the British government offered to pay people for every dead cobra they brought in. The money was good and eventually, people started raising cobras for the sole purpose of killing them to collect the county.

This is exactly what happens with most innovation metrics.

Because companies are so keen to measure and track progress, they set metrics they can measure. Those measurable metrics quickly become targets.

For example, one of my clients was eager to “fill their innovation funnel” and so they set a metric for the number of new ideas submitted each quarter. It didn’t take long before the innovation team spent most of the last day of each quarter frantically submitting “new ideas” so that they could hit the target.

The next day, they would go into the system and reject all the frantically submitted ideas because the ideas didn’t meet established qualitative criteria for strategic fit, scalability, or business potential.

At the end of the year, management was dumbfounded – despite getting thousands of ideas, the team had yet to pilot an idea, let alone launch a new business and generate revenue.

Metrics aren’t satisfying if they aren’t effective in achieving your ultimate goal

Was killing lots of cobras Britain’s ultimate goal? No.

They wanted to decrease the cobra population.

But killing cobras was a key step in decreasing the population and it was easier and faster to measure and track the number of cobras killed.

Was getting lots of ideas my client’s ultimate goal? No.

They needed to increase revenue by 50% in the next 5 years.

But getting ideas was a key step in creating a new stream of revenue and it was easier and faster to measure and track the number of ideas submitted.

How to Create Effective Innovation Metrics

State the ONE Why.

This is the hardest part of setting metrics because there are lots of reasons to pursue innovation. But we have to remember that innovation is a means to an end and effective metrics focus on the end, not the means.

I like to use the 5 Whys to get to the ultimate goal. Here’s a rough approximation (with completely made-up numbers) of the conversation I had with the client mentioned above:

- ME: Why do you want # of new ideas in the funnel each quarter?

- Client: Because we need that many to get 4 new products to pilot

- Me: Why do you need to pilot 4 new products?

- Client: Because we have a 50% pilot success rate

- Me: OK, so you need to launch 2 new products. Why two?

- Client: Because our new products generate $100M in Yr 1 revenue

- Me: Why do you need $200M in new revenue each year?

- Client: Because we have a $1B gap between what we promised to shareholders and what we’re on track to deliver in 5 years

Their ultimate goal was to close a $1B revenue gap in 5 years, not generate # new ideas per year.

Set interim milestones.

Achieving an ultimate goal takes years of hard work and you may need to pivot or readjust expectations along the way. For that reason, it’s important to set interim milestones, not as decision points but as markers for when to pull your head out of the day-to-day details and assess whether or not you are on track and, if not, what you need to change.

Using the same client as an example, we could have decided that $1B in new revenue in 5 years meant that we needed to generate $200M in new revenue every year. But, as we talked through things, we realized that it would take time to fill the innovation funnel AND build the organizational capability to develop, test, and launch new products. As a result, we should set revenue goals that increased each year, reflecting the organization’s increasing innovation effectiveness.

Explore the MANY Hows.

Innovation may be one way to achieve your ultimate goal but there are lots of others and it’s important to stay open to all of them.

For my client, we quickly realized that it wasn’t reasonable to rely solely on organic innovation to close the $1B revenue gap. Instead, we needed to explore multiple approaches from organic innovation to M&A and everything in between.

In closing…

It’s easy to fall into the trap of “satisfying” metrics that measure activity.

It’s a bit harder to evade the trap by identifying effective metrics that measure progress to an ultimate goal.

But, I can assure you, achieving that ultimate goal is way beyond satisfying.