by Robyn Bolton | Feb 13, 2024 | Innovation, Leadership

The road to hell is paved with good intentions, and nowhere is that more true than in innovation.

That’s one of the insights I took away from InnoLead’s Q1 report on corporate innovation priorities. The report is an eye-opening look at the impact of AI on corporate innovation as experienced by corporate entrepreneurs themselves. But before deep diving into that topic, the report’s authors shared intriguing data about member companies’ innovation structure, leadership engagement, organizational connections, and results. Nestled amongst the charts were several that, when taken together, got my Spidey senses tingling.

61.0% of innovation teams are “directly under a high-visibility leader with a broad company focus.”

This is great because innovation needs senior leaders’ support and active engagement to survive, let alone survive for long enough to produce meaningful results. Add this to the fact that 45% of senior leadership teams frequently discuss the “progress and value of the innovation program,” and all signs point to innovation as a strategic priority.

But (you knew there was a but, didn’t you)…

If “broad company focus” means “no P&L responsibility,” we have a problem. In every for-profit company I’ve worked for and with, people with P&L responsibility have greater power, influence, and access to resources than people without a P&L. This division may not feel fair, but it makes sense – the people who bring in profit and revenue will always be more influential than people who represent “cost centers.”

You can see the impact of P&L owners who are, understandably, focused entirely on delivering short-term results throughout the report – 75% of companies have shifted their focus more towards near-term priorities, and 61% shifted their innovation portfolio away from Horizon 3 (also known as radical, breakthrough, or disruptive innovation).

As for all those discussions, it’d be great if they focused on walking the talk of innovation. But suppose it’s only innovation platitudes or, worse, questioning innovation’s ROI. That doesn’t bode well for the “high-visibility leader with broad company focus,” the innovation team, or the company’s culture.

71.2% of innovation teams’ customers or business partners are unaware of the team’s existence, don’t engage, or engage only occasionally.

Welcome to Innovation Island! Where the cool people work on cool things in cool offices while all you drones slave away doing the same thing you’ve always done and making the money that pays for the cool people to do cool things in their cool offices.

I’m sure this isn’t the message the innovation team intends to send, but it’s the one received by most organizations.

When arguing for Innovation Island, managers often point to the organizational antibodies likely to swarm and kill H3/radical/breakthrough innovation and even some H2/adjacent innovations. They’re right, and those innovations must be “protected.” But not every innovation needs protection. H2 and certainly H1 innovations, where most portfolios are now, should be shared with the core business because the core business will eventually run them.

The bigger problem, in my opinion, is that innovation teams don’t seem to be reaching out to others in the organization. Like the P&L owners they report to, people in the core business are busy running the business and generating revenue. Very few have the time or energy to seek out the innovation team to discuss and explore innovation. Companies that want to build a culture of innovation need to turn their innovators into evangelists, not residents of an island connected to the mainland by a single drawbridge.

23.4% of innovation teams are considered outsiders or actively undermined by other functions and business units.

This may not sound bad, but add to it the 55.0% that are “somewhat integrated with occasional collaboration” with other departments and business units, and you may be tempted to believe that Innovation Island would be wise to invest in a surface-to-air missile defense system.

Sadly, this perception of the innovation team as “The Others” isn’t surprising when considering that the most important tactic for building a relationship between innovation and the functions or business units is already having strong relationships and interpersonal trust (75.3% of respondents). The least effective (4.7% of respondents) is “writing down shared objectives and expectations.” So, no, the email you sent is not enough to win friends and influence people.

Bottom line

Well-intended companies appoint a senior executive to lead the innovation team because they’ve been told that doing so is powerful proof that innovation is a strategic priority. They hire outsiders to inject new thinking into the organization because they know that “what got you here won’t get you there.” They cordon the team and their work off from the rest of the organization because they read that separation is essential to preserving innovation’s disruptive nature.

But if the senior executive doesn’t have the organizational power and influence that comes with P&L ownership, the team doesn’t have strong personal relationships with others in the business, and other functions and business units don’t know the team exists or how to interact with it, innovation will go nowhere.

But that’s better than where it could go.

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 31, 2024 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

Most customer research efforts waste time and money because they don’t produce insights that fuel innovation. Well-meaning businesspeople say they want to “learn what customers want,” yet they ask questions better suited to confirming their own ideas or settling internal debates. Meanwhile, eager consumers dutifully provide answers despite the nagging belief that they’re being asked the wrong questions.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In fact, you can get profound revelations into consumers’ psyche, motivations, and behaviors if you do one thing – channel your inner Elmo.

First, a confession

I find Elmo deeply annoying. I grew up watching Sesame Street, and I still get an astounding amount of joy watching Big Bird, Mr. Snuffleupagus, Cookie Monster, Bert and Ernie, Grover, and Oscar the Grouch (especially when Oscar channels his inner Taylor Swift).

Elmo moved to Sesame Street in 1985, and it hasn’t been the same since. He’s designed to reflect the mental, emotional, and intellectual capabilities of a 3.5-year-old, and, in that aspect, his creators were wildly successful. I fully acknowledge that Elmo plays a vital role in the mission of Sesame Street and that people of all ages love Elmo. But Elmo makes my ears bleed, and I will never be ok with the fact that Elmo refers to himself in the third person.

This is why my recommendation to channel your inner Elmo is shocking and extremely serious.

Next, an explanation

On Monday, Elmo posted on X (yes, the minimum age limit is 13, but his mom and dad help him run the account, so it’s apparently okay), “Elmo is just checking in! How is everybody doing?”

180 million views, 120,000 likes, and 13,000 comments later, it was clear that no one was okay.

And lest you think this was Gen Z trauma dumping on their ol’ pal Elmo, Dionne Warwick, T-Pain, and Today Show anchor Craig Melvin responded with their struggles. Comments ranged from, “Mondays are hard” to “Elmo I’m gonna be real I am at my f—ing limit,’ to “Elmo each day the abyss we stare into grows a unique horror. one that was previously unfathomable in nature. our inevitable doom which once accelerated in years, or months, now accelerates in hours, even minutes. however I did have a good grapefruit earlier, thank you for asking.”

Wow. Thank goodness for that grapefruit.

There are a lot of theories about why Elmo’s post touched a nerve – it’s January and we’re tired, it’s easier to share our struggles online than in person, or we still enjoy “that wholesome and sincere bond from childhood that makes us want to share.”

I’m sure all those are true, and I think it’s something more, something we can all learn and do.

Now, the secret

Elmo may be a red, hairy, 3.5-year-old muppet. Still, he nailed the behaviors required to get people to open up and share their inner worlds – the very thoughts, beliefs, and motivations that enable others to create and offer impactful and innovative solutions.

Here’s what Elmo did (and you should, too):

- Show that you’re genuinely curious: Elmo didn’t open with the standard “How are you?” that if answered with anything other than the socially acceptable “Fine,” results in awkward silence and inner panic. Elmo opened by declaring his intent – checking in – and then asked a question. Because of that, we understood his motivation was genuine, and he wanted an honest answer.

- Ask open-ended questions: Elmo didn’t ask a closed question that can be answered with yes or no. He asked a question that allowed people to share as much or as little as they wanted and that could act as a springboard to a deeper conversation.

- Listen silently and without judgment: Elmo didn’t follow up his original tweet with options like “Are you doing ok, or not ok, or are you happy, or sad, or mad, or…” Elmo asked a question and then listened (read the responses) without jumping back into the conversation or firing off follow-up questions.

- Acknowledge and thank the person sharing: On Tuesday, Elmo responded but not by skipping off to the next scheduled post. He acknowledged the response by opening with, “Wow! Elmo is glad he asked!” He didn’t share his opinion or immediately ask another question. Instead, he thanked people for sharing, acknowledged that he heard their responses, and was grateful.

- Do something with what was shared: Even if you do #4, it’s tempting to move on to the next question. Don’t. Elmo didn’t. Instead, he wrote that he “learned that it is important to ask a friend how they are doing.” He also wrote that he “will check in again soon, friends! Elmo loves you.” You don’t have to profess your love but do respond with what you learned and what it makes you wonder.

People can’t tell you what to create because they don’t know what you know. But they can tell you the problems they have. If you’re willing to listen (just don’t talk about yourself in the third person, you’re not a muppet).

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 23, 2024 | Innovation, Just for Fun, Leadership, Stories & Examples

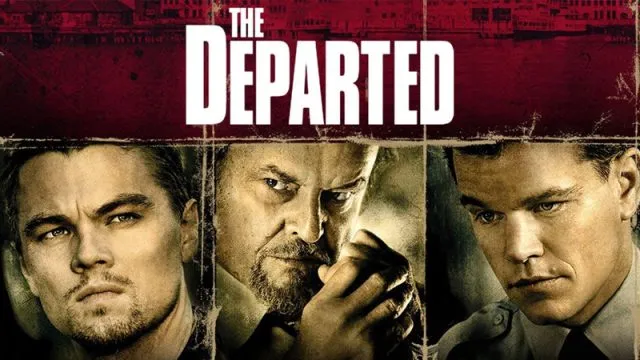

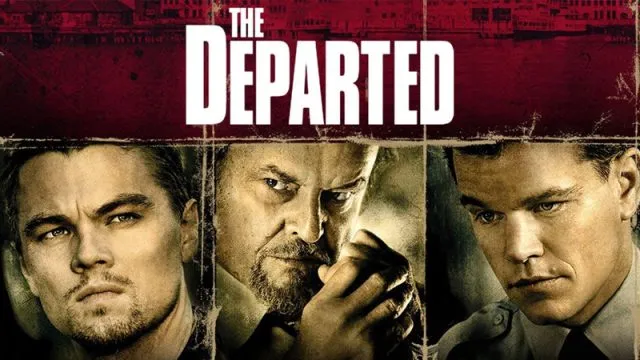

It’s award season, which means that, as a resident of Boston, I have the responsibility and privilege to talk about The Departed (pronounced: The Dep-ah-ted). The film won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2007 and earned Martin Scorsese his first, and to date only, Academy Award for Best Director. It is also chock-full of great lessons for corporate innovators.

Quick Synopsis

If you’ve seen The Departed, you can skip this part. If you haven’t, why not and read on.

The Departed is loosely based on notorious Boston crime boss Whitey Bulger and features three main characters:

- Frank Costello (Jack Nicholson), a vicious and slightly unhinged Irish mob boss

- Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon), a Massachusetts State Trooper in the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) formed to catch Costello, who, in his spare time, is a spy for Costello.

- Billy Costigan (Leonardo DiCaprio), a police academy recruit who goes undercover to infiltrate Costello’s organization

But wait! There’s more. Alec Baldwin plays Colin’s SIU boss, George Ellerby. Martin Sheen and Mark Wahlberg (who received an Oscar nomination for this role) play Billy’s Mass State Police (MSP) bosses, Captain Queenan and Staff Sergeant Dignam, respectively. Completing the chaos is Vera Farmiga, who plays Madolyn Madden, Colin’s girlfriend and Billy’s court-ordered psychiatrist.

There’s a lot of other stuff going on, but that gives you enough context for the following quotes to hopefully make sense.

Listen to the words people use.

Colin (after Dignam refuses to hand over undercover files): I need those passwords.

Ellerby: No, you want those passwords

It’s not often that Ellerby says something useful, let alone wise, but he nails it with this one. Colin wants the passwords to Dignam’s files on undercover agents because it will make both Colin’s official job of finding Costello’s rat in the MSP and his unofficial job of finding the MSP officer in Costello’s crew easier. He doesn’t need the passwords, however, because, with enough time and effort, he can find the rats he’s looking for.

When we hear from customers that they want something, it’s tempting to run off and create it. But as Ellerby points out, wants and needs are different. Just because customers want something doesn’t mean they are willing to pay for or change their behavior to get and use it.

Figuring out what a customer needs is difficult because it requires them to trust you enough to admit they have a problem they can’t solve. It’s also difficult because most of us have access to solutions to our functional needs (think the bottom few layers of Maslow’s hierarchy). As a result, the needs consumers grapple with tend to be emotional and social, and it’s far more challenging to admit those to a stranger, especially in a focus group or product-focused interview.

How you feel impacts everyone around you

Madolyn (after a counseling session): Why is the last patient of the day always the hardest?

Billy: Because you’re tired, and you don’t give a sh*t. It’s not super-natural.

Billy and Madolyn get off to a rough start in their first counseling session, culminating in Billy asking for a prescription for Valium. Madolyn calls him out for “drug-seeking behavior” and throws two Valiums across the desk before Billy storms out. A few minutes later, Madolyn catches up with Billy, hands him a prescription for Valium, and asks the above question.

Being a corporate innovator can be difficult, sometimes soul-crushing work (ask the good people at Store 8). It can also be thrilling and inspiring. It can even be all those things in one day. That’s what makes it tiring, even when you give a sh*t.

Managing your energy and monitoring your behavior are leadership qualities we don’t discuss often enough. It’s okay to be exhausted after a day of facilitating ideation sessions or intense strategic meetings. It’s normal to be frustrated after a contentious conversation or demotivated when you get bad news. But leaders usually find a way to not take those emotions out on their teams. And, in the rare instance when they punish the team for someone else’s sin, they apologize and explain.

Your job is not your identity.

Billy: Look, I just want my identity back, all right? That’s all.

Colin: All right, I understand. You want to be a cop again.

Billy: No, no, being a cop’s not an identity. I want my identity back.

Towards the end of the film, Billy is tired of working undercover and reports to MSP headquarters to complete the paperwork required to expunge his criminal record and get his identity back. That’s when Colin makes the same mistake most of us make and confuses Billy’s job with his identity.

We spend so much time at work. We rely on our paychecks for so much. We even introduce ourselves to new people using our job titles. It’s easy for your job to feel like your identity, especially when your job aligns so closely with your deeply held beliefs and values. But your job is not your identity. You are still a Tempered Radical, even without your corporate title. You are still an optimistic problem-solver, even when it’s been months since your last brainstorming session.

You are an innovator, even if you don’t have a business card to prove it.

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 17, 2024 | Innovation, Just for Fun

Fabric & Home Care Marketing

That is the job title on my very first business card. I remember holding the card in my hands, staring at it for entirely too long, and thinking, “This is sooooo boring. Even my parents won’t be impressed.”

To be fair to P&G, that was the job title on the business card of everyone in marketing in the business units. The company didn’t put job titles on the card for security reasons (or at least that’s what my boss told me when I politely asked why my title wasn’t on the card).

I am older now and should have the maturity to accept the bland and nondescript title on my first business card. But I’m not. It’s still boring, and it shouldn’t be because we were working on innovation projects with code names and outfoxing corporate spies in the airport (another story for another post). We were doing cool stuff and should have cool titles to show for it!

So, to right the wrong inflicted upon me and the countless others stuck with boring job titles despite doing brave, bold, and daring things, today is Make Your Own Title Day (business cards not included)

Intrapreneur

PRO: Short and sweet with a great original definition – “dreamers who do”

CON: Everyone will think you misspelled Entrepreneur

Pirates in the Navy

PRO: Title of a book by one of the foremost thinkers in the field of corporate innovation and a phrase inspired by Steve Jobs’ statement that it’s better to be a pirate than be in the Navy. It also creates the excuse to wear an eyepatch, talk like a pirate, and keep a parrot in the office.

CON: People are afraid of pirates. You don’t want people to be scared of you.

Rebel Smuggler

PRO: Also the basis of a book with the benefit of being a cool title that doesn’t scare people. Plus, who wanted this to describe them:

Whether you’re are a Rebel in a functional company or a Smuggler in a dysfunctional company, you are the essential part of any transition. You are the catalyst that transforms the caterpillar into a butterfly. You disrupt the status quo and create opportunities for growth,

You are not the caterpillar nor the butterfly. You are the magic that prompts the transition.”

Natalie Neelan, Rebel At Work: How to Innovate and Drive Results When You Aren’t the Boss

CON: Legal and Corporate Security may not love the “Smuggler” part of the title

Tempered Radical

PRO: A more “professional” version of Rebel Smuggler, and it’s a term used in HBR, so you know it’s legit. Here’s how they’re described:

They all see things a bit differently from the “norm.” But despite feeling at odds with aspects of the prevailing culture, they genuinely like their jobs and want to continue to succeed in them, to effectively use their differences as the impetus for constructive change. They believe that direct, angry confrontation will get them nowhere, but they don’t sit by and allow frustration to fester. Rather, they work quietly to challenge prevailing wisdom and gently provoke their organizational cultures to adapt. I call such change agents tempered radicals because they work to effect significant changes in moderate ways.

Debra Meyerson, “Radical Change, the Quiet Way” in HBR (October 2001)

CON: Sometimes working quietly doesn’t work. Sometimes, you need to make a ruckus.

[YOUR TITLE HERE]

What title do you want to give yourself and other innovators?

Drop your suggestion in the comments (and feel free to print up new business cards)!

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 2, 2024 | Innovation

“You sound stupid when you use the word ‘_____________’ because you’re trying to sound smart.”

Mark Cuban

What goes in the blank?

For Mark Cuban, it’s “cohort” because “there’s no reason to ever use the word ‘cohort’ when you could use the word ‘group.’ A cohort is a group of people. Say ‘group.’ Always use the simpler word.”

For one of my former bosses, it was “breakthrough.” He would throw you out of the room if you used that word. Not physically throw you out, but he was a big guy and could if you didn’t exit on your own.

For me, it’s “disrupt” (and all its forms) because applies (as originally intended by Clayton Christensen) in only about 0.1% of the instances in which it’s used.

There are other candidates.

Lots of other candidates.

In fact, I would go so far as to propose the biggest buzzword of them all: INNOVATION.

“Innovation” does not make you sound smart.

Here is a very short list of the most commonly heard statements about innovation.

- Innovation is a priority.

- Innovation is key to our growth.

- We need to be more innovative.

- We want to build/are committed to building a culture of innovation

- Let’s innovate!

What do these statements even mean?

- It’s great that innovation is a priority and key to our growth. Hasn’t that always been the case? What is changing? How is that translating into action? What do you expect from me?

- Agree we should be more innovative. How? What does “more innovative” look like?

- Definitely want to be part of a culture of innovation. What does that mean? How is that different than our current culture? What changes? How do we make sure the changes stick?

- Sigh. Eye roll.

Saying what you mean makes you sound smart.

Always use the simpler word, and, in the case of innovation, there is always a simpler word or phrase. Consider:

- Grow revenue from our existing businesses

- Create new revenue streams

- Grow profit in our existing businesses

- Grow profit by launching new high-profit businesses

- Stay ahead of the competition

- Create a new category

- Launch a new product

- Better serve our current customers

- Serve new customers

- Update/extend our current products

- Increase the effectiveness of our marketing spend

- Revise our business model to reflect changing consumer and customer expectations

- Launch a low-cost and good-enough offering that appeals to non-consumers

You sound smart when you use the word(s) that most clearly, concisely, and unambiguously communicate your idea or intention. “Innovation” does not do that.

Saying “innovation” AND what you mean makes you sound wicked smaht

“Innovation” on its own is lazy. Simpler words and phrases aren’t nearly as sexy (I can’t imagine Fast Company coming out with “The World’s Best Companies at Creating New Revenue Streams” list).

But when you put them together – smart and sexy:

- Innovation is a priority. As a result, we are committing a minimum of $50M a year for the next five years to…

- Innovation is key to growth. As a result, we are doubling our investment in…

- We need to be more innovative. To achieve this, we are changing how we measure and incentivize executive performance to encourage long-term investments.

- We want to build a culture of innovation. As a first step in this process, we are making Kickbox available to any interested employee.

Let’s Innovate (Nope, don’t say this. It’s too cheesy)

Say what you mean.

If you don’t, people will think you don’t mean what you say.

What other words would you add to this rant?

by Robyn Bolton | Dec 10, 2023 | Innovation, Leadership, Stories & Examples

In September 2006, I moved to Copenhagen, Denmark, on a temporary assignment with BCG. As one does when arriving somewhere for an extended period, I went to the grocery store to stock my kitchen.

Since the grocery store was on the ground floor of my building, I bought enough food for a few breakfasts and dinners, made note of the other offerings for future trips, and learned through painful public embarrassment that one must purchase grocery bags (and those bags are nowhere near the checkout lane).

The following day, yogurt was on the menu, and I grabbed the first of the three options I had bought the previous day – a small container of strawberry yogurt.

My heart sank when I peeled off the top.

Instead of super healthy, organic, natural (I’m in Scandinavia, for crying out loud!) yogurt, the stuff in my cup was a rather suspicious beige with dark brown flecks.

Stifling my instinct to dry heave, I chucked the cup into the garbage, along with the five other cups in the clearly spoiled pack, and pulled Brand #2 out of the refrigerator. Surely, this strawberry yogurt would be safe to eat.

But it, too, was beige. A lighter beiger and without the disturbing brown flecks. But still beige.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I muttered. Admittedly, the grocery store was more of a glorified convenience store, but c’mon, how hard is it to keep track of Sell By dates?

Into the garbage, it went. Out of the refrigerator came Brand #3 (Yes, I take a portfolio approach to innovation AND food purchases)

Closing my eyes and saying a quick prayer to both the grocery and yogurt gods, I peeled open the yogurt. Not beige but a slight hint of pink, just enough to reassure me that it contained strawberries and hadn’t curdled but not so much that I suspected an American-amount of food coloring.

Later that day…

At lunch, my new colleagues asked how I was settling in. I regaled them with my “bumbling American experiencing culture shock in a country where she looks (and is initially treated like) a local” stories.

As we gathered up our dishes and returned to the kitchen, I commented that I was surprised that my local grocery would keep expired products on the shelf. When they echoed my surprise, I told them about the spoiled yogurt and that 2 of the three brands I purchased were bad.

Based on the glances they exchanged, I knew I had another story to add to an already uncomfortably full book.

It turns out that. The “good” yogurt I ate that morning was from the lowest quality brand, one that no self-respecting Dane would consider eating but that is sold to unsuspecting foreigners (Hi, that’s me). The “bad” yogurt was from respected all-natural brands. All yogurt, they explained, falls somewhere in the spectrum from white to beige or even tan. That’s why they print the flavor name and a picture of the fruit on the label.

How often do we make the same mistake?

How often do we reject something because it’s not what we expect to see? Because it’s not what we’re used to?

Maybe not often when it comes to yogurt, but what about other more important things, like:

- Trends

- Technologies

- Ideas

- Business Models

- Startups

- People

And what happens when we don’t have people willing to point out that we’re no longer in a place where our status quo applies?