by Robyn Bolton | Sep 23, 2025 | Innovation, Metrics, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

It’s time for your company’s All-Hands meeting. Your CEO stands on stage and announces ambitious innovation goals, talking passionately about the importance of long-term thinking and breakthrough results. Everyone nods enthusiastically, applauds politely, and returns to their desks to focus on hitting this quarter’s numbers. After all, that’s what their bonuses depend on.

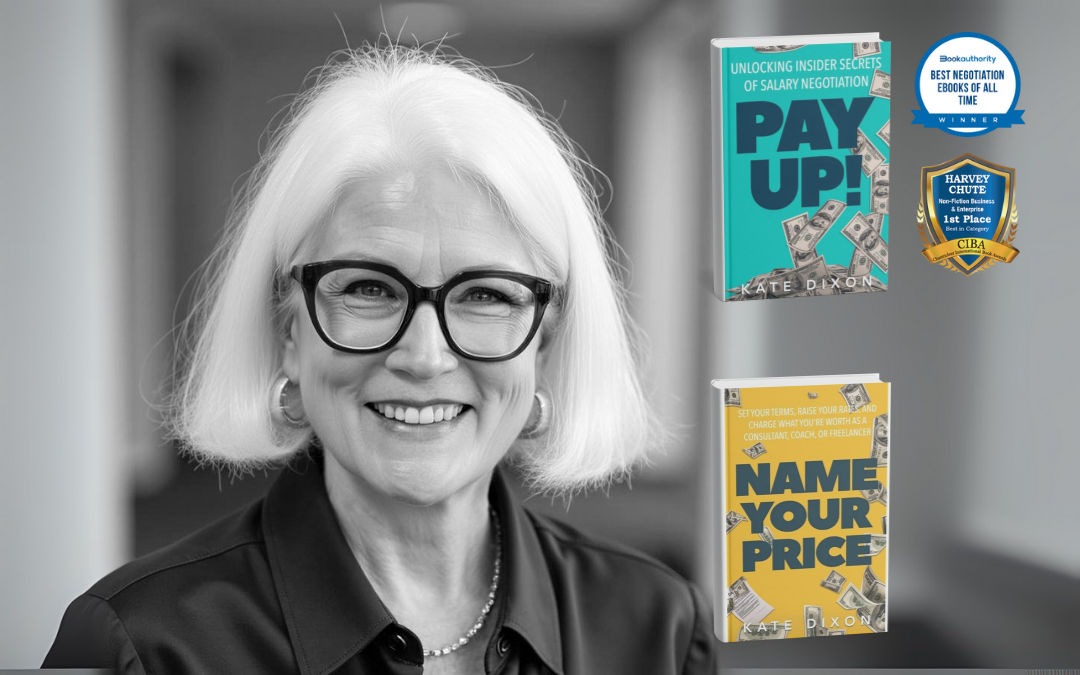

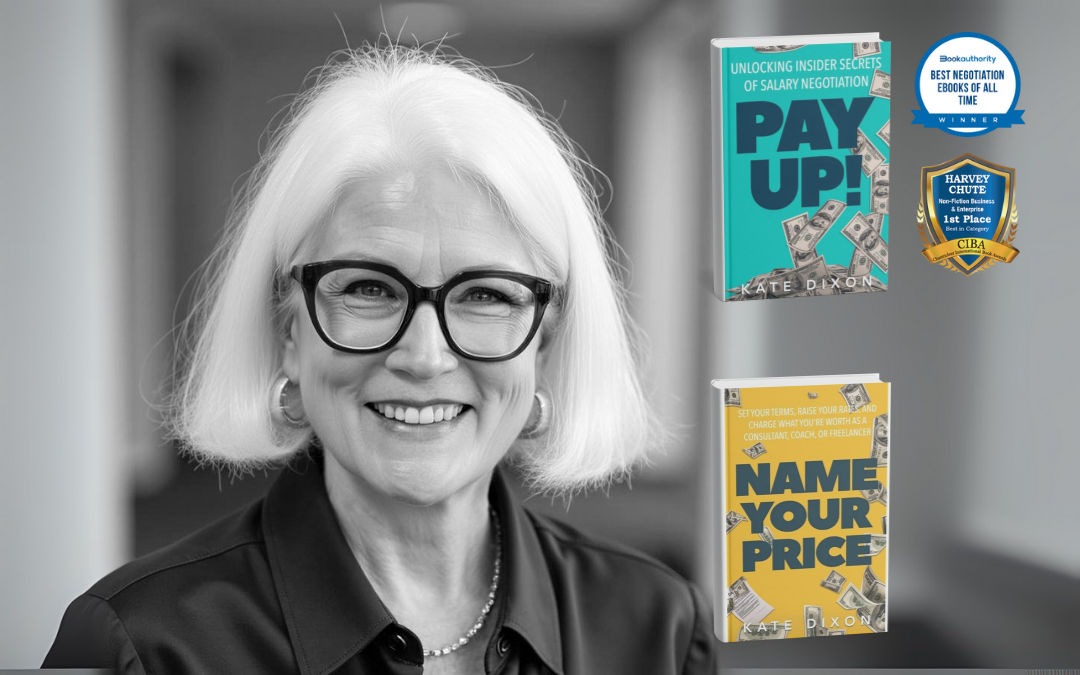

Kate Dixon, compensation expert and founder of Dixon Consulting, has watched this contradiction play out across Fortune 500 companies, B Corps, and startups. Her insight cuts to the heart of why so many innovation initiatives fail: we’re asking people to think long-term while paying them to deliver short-term.

In our conversation, Kate revealed why most companies are inadvertently sabotaging their own innovation efforts through their compensation structures—and what the smartest organizations are doing differently.

Robyn Bolton: Kate, when I first heard you say, “compensation is the expression of a company’s culture,” it blew my mind. What do you mean by that?

Kate Dixon: If you want to understand what an organization values, look at how they pay their people: Who gets paid more? Who gets paid less? Who gets bigger bonuses? Who moves up in the organization and who doesn’t? Who gets long-term incentives?

The answers to these questions, and a million others, express the culture of the organization. How we reward people’s performance, either directly or indirectly, establishes and reinforces cultural norms. Compensation is usually the biggest, if not the biggest, expenses that a company has so they’re very thoughtful and deliberate about how it is used. Which is why it tells you what the company actually does value.

RB: What’s the biggest mistake companies make when trying to incentivize innovation?

KD: Let’s start by what companies are good at when it comes to compensations and incentives. They’re really good about base pay, because that’s the biggest part of pay for most people in an organization. Then they spend the next amount of time and effort trying to figure out the annual bonus structure. After that comes other benefits, like long term incentives, assuming they don’t fall by the wayside.

As you know, innovation can take a long time to payout, so long-term incentives are key to encouraging that kind of investment. Stock options and restricted shares are probably the most common long-term incentives but cash bonuses, phantom stock, and ESOP shares in employee-owned companies are also considered long term incentives.

Large companies are pretty good using some equity as an incentive, but they tie it t long term revenue goals, not innovation. As you often remind us, “innovation is a means to the end, which is growth,” so tying incentives to growth isn’t bad but I believe that we can do better. Tying incentives to the growth goals and how they’re achieved will go a long way towards driving innovation.

RB: I’ve worked in and with big companies and I’ve noticed that while they say, “innovation is everyone’s job,” the people who get long-term incentives are typically senior execs. What gives?

Long-term incentives are definitely underutilized, below the executive level, and maybe below the director level. Assuming that most companies’ innovation efforts aren’t moonshots that take decades to realize, it makes a ton of sense to use long-term incentives throughout the organization and its ecosystem. However, when this idea is proposed, people often pushback because “it’s too complex” for folks lower in the organization, “they wouldn’t understand.” or “they won’t appreciate it”. That stance is both arrogant and untrue. I’ve consistently seen that when you explain long-term incentives to people, they do get it, it does motivate them, and the company does see results.

RB: Are there any examples of organizations that are getting this right?

We’re seeing a lot more innovative and interesting risk-taking behaviors in companies that are not primarily focused on profit.

Our B Corp clients are doing some crazy, cool stuff. We have an employee-owned company that is a consulting firm, but they had an idea for a software product. They launched it and now it’s becoming a bigger and bigger part of their business.

Family-owned or public companies that have a single giganto shareholder are also hotbeds of long-term thinking and, therefore, innovation. They don’t have that same quarter to quarter pressure that drives a relentless focus on what’s happening right now and allows people to focus on the future.

What’s the most important thing leaders need to understand about compensation and innovation?

If you’re serious about innovation, you should be incentivizing people all over the organization. If you want innovation to be a more regular piece of the culture so you get better results, you’ve got to look at long term incentives. Yes, you should reward people for revenue and short-term goals. But you also need to consider what else is a precursor to our innovation. What else is makes the conditions for innovating better for people, and reward that, too.

Kate’s insight reveals the fundamental contradiction at the heart of most companies’ innovation struggles: you can’t build long-term value with short-term thinking, especially when your compensation system rewards only the latter.

What does your company’s approach to compensation say about its culture and values?

by Robyn Bolton | Aug 20, 2025 | AI, Metrics

Sometimes, you see a headline and just have to shake your head. Sometimes, you see a bunch of headlines and need to scream into a pillow. This week’s headlines on AI ROI were the latter:

- Companies are Pouring Billions Into A.I. It Has Yet to Pay Off – NYT

- MIT report: 95% of generative AI pilots at companies are failing – Forbes

- Nearly 8 in 10 companies report using gen AI – yet just as many report no significant bottom-line impact – McKinsey

AI has slipped into what Gartner calls the Trough of Disillusionment. But, for people working on pilots, it might as well be the Pit of Despair because executives are beginning to declare AI a fad and deny ever having fallen victim to its siren song.

Because they’re listening to the NYT, Forbes, and McKinsey.

And they’re wrong.

ROI Reality Check

In 20205, private investment in generative AI is expected to increase 94% to an estimated $62 billion. When you’re throwing that kind of money around, it’s natural to expect ROI ASAP.

But is it realistic?

Let’s assume Gen AI “started” (became sufficiently available to set buyer expectations and warrant allocating resources to) in late 2022/early 2023. That means that we’re expecting ROI within 2 years.

That’s not realistic. It’s delusional.

ERP systems “started” in the early 1990s, yet providers like SAP still recommend five-year ROI timeframes. Cloud Computing“started” in the early 2000s, and yet, in 2025, “48% of CEOs lack confidence in their ability to measure cloud ROI.” CRM systems’ claims of 1-3 years to ROI must be considered in the context of their 50-70% implementation failure rate.

That’s not to say we shouldn’t expect rapid results. We just need to set realistic expectations around results and timing.

Measure ROI by Speed and Magnitude of Learning

In the early days of any new technology or initiative, we don’t know what we don’t know. It takes time to experiment and learn our way to meaningful and sustainable financial ROI. And the learnings are coming fast and furious:

Trust, not tech, is your biggest challenge: MIT research across 9,000+ workers shows automation success depends more on whether your team feels valued and believes you’re invested in their growth than which AI platform you choose.

Workers who experience AI’s benefits first-hand are more likely to champion automation than those told, “trust us, you’ll love it.” Job satisfaction emerged as the second strongest indicator of technology acceptance, followed by feeling valued. If you don’t invest in earning your people’s trust, don’t invest in shiny new tech.

More users don’t lead to more impact: Companies assume that making AI available to everyone guarantees ROI. Yet of the 70% of Fortune 500 companies deploying Microsoft 365 Copilot and similar “horizontal” tools (enterprise-wide copilots and chatbots), none have seen any financial impact.

The opposite approach of deploying “vertical” function-specific tools doesn’t fare much better. In fact, less than 10% make it past the pilot stage, despite having higher potential for economic impact.

Better results require reinvention, not optimization: McKinsey found that call centers that gave agents access to passive AI tools for finding articles, summarizing tickets, and drafting emails resulted in only a 5-10% call time reduction. Centers using AI tools to automate tasks without agent initiation reduced call time by 20-40%.

Centers reinventing processes around AI agents? 60-90% reduction in call time, with 80% automatically resolved.

How to Climb Out of the Pit

Make no mistake, despite these learnings, we are in the pit of AI despair. 42% of companies are abandoning their AI initiatives. That’s up from 17% just a year ago.

But we can escape if we set the right expectations and measure ROI on learning speed and quality.

Because the real concern isn’t AI’s lack of ROI today. It’s whether you’re willing to invest in the learning process long enough to be successful tomorrow.

by Robyn Bolton | Feb 18, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Metrics, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

Innovation is undergoing a metamorphosis, and while it may seem like the current goo-stage is the hard part (it’s certainly not easy!), our greatest challenge is still ahead. Because while we may emerge as beautiful butterflies, we still need to get buy-in for change from a colony of skeptical caterpillars who’ve grown weary of transformation talk.

The Old Playbook Is Dead, Too

Picture this: A butterfly lands, armed with PowerPoint slides about “The Future of Leaf-Eating” and projections showing “10x Nectar Collection Potential.” The caterpillars stare blankly, having seen this show before.

The old approach – big presentations, executive sponsorship, and promises of massive returns within 24 months – isn’t just ineffective. It’s harmful. Each failed transformation makes the next one harder, turning your caterpillars more cynical and more determined to cling to their leaves.

The Secret Most Change Experts Miss

Butterflies don’t convince caterpillars to transform by showing off their wings. They create conditions where transformation feels possible, necessary, and safe. Your job isn’t to sell the end state – it’s to help others see their own potential for change.

Here’s how:

Start With the Hungriest Caterpillars

Find those who feel the limitations of their current state most acutely. They’re not satisfied with their current leaf, and they’re curious about what lies beyond. These early adopters become your first chrysalis cohort.

Make it About Their Problems, Not Your Vision

Instead of talking about transformation, focus on specific pain points. “Wouldn’t it be easier to reach that juicy leaf if you could fly?” is more compelling than “Flying represents a paradigm shift in leaf acquisition strategy.”

Build a Network of Proof

Every successful mini-transformation creates evidence that change is possible. When one caterpillar successfully navigates their chrysalis phase, others pay attention. Let your transformed allies tell their stories.

Set Realistic Expectations

Metamorphosis takes time and isn’t always pretty. Be honest about the goo phase – that messy middle where things fall apart before they come together. This builds trust and prepares people for the real journey, not the sanitized version.

Where to Start

- Identify your first chrysalis cohort – the people already feeling the limits of their current state

- Focus on solving immediate problems that showcase the benefits of change

- Document and share small victories, letting others tell their transformation stories

- Create realistic timelines that acknowledge both quick wins and longer-term metamorphosis

What’s your experience? Have you successfully guided a transformation without relying on buzzwords and fancy presentations? Drop your stories in the comments.

After all, we’re all just caterpillars and butterflies helping each other find our wings.

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 22, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Metrics, Stories & Examples

“Consider this question: If workers are hobbled by 1,000 rules, does it make a meaningful difference to reduce them to only 900?”

The answer is No. In fact, this is precisely why most attempts at fighting bureaucracy fail – and why true transformation requires starting completely fresh.

Bill Anderson, CEO of Bayer, knows this and isn’t afraid to admit it. When he took the helm in June 2023, he discovered a company paralyzed by bureaucracy. Instead of trying to optimize the system, he looked at the company’s “1,362 pages” of employee rules and knew the entire structure needed to change.

Breaking the Stranglehold

As Anderson stated in Fortune, “There was a time for hierarchical, command-and-control organizations – the 19th century, to be exact, when many workers were illiterate, information traveled at a snail’s pace, and strict adherence to rules offered the competitive advantage of reliability.”

The modern reality is different. Today’s Bayer employs highly skilled experts, operates at digital speed, and competes in markets where, as Anderson observes, “the most reliable companies are the most dynamic.”

The challenge wasn’t just the encyclopedic rulebook. The organization’s “12 levels of hierarchy” created what Anderson called “unnecessary distance between our teams, our customers, and our products.” In today’s innovation-driven market, this industrial-age structure threatened the company’s future.

Unleashing Innovation

Anderson’s solution? “Dynamic Shared Ownership” – a radical model that puts 95% of decision-making in the hands of the people actually doing the work. Instead of annual budgets and endless approvals, self-directed teams work in 90-day sprints with the autonomy to make real-time decisions.

The results are already showing. Take Vividion, Bayer’s independently operated subsidiary. Operating in small, autonomous teams, they went from FDA approval to first patient dosing in just six weeks. They’re now on track to produce one or two new drug candidates for clinical testing every year.

Speed Becomes Reality

The impact extends across the organization. Bayer’s scientists have transformed their plant breeding process, reducing cycles from “five years down to merely four months.”

In the consumer health division, teams have accelerated their development timelines significantly, reducing product launch schedules “by up to nine months” in Asia. Within their first two months under the new system, these teams generated millions in additional value.

While financial markets remain uncertain about this transformation, one crucial metric suggests it’s working: employee retention has improved. The scientists, researchers, and product developers – the people doing the innovative work – are showing their confidence in this dramatic shift toward autonomous operation.

Why This Matters & What to do Next

For most of us, the question isn’t whether our organization has too much bureaucracy – it almost certainly does. The question is: what are you going to do about it?

Try this – Create a small, autonomous team with a 90-day mission. Give them real decision-making power and see what they can accomplish when freed from bureaucratic constraints.

Remember Anderson’s key insight: reducing rules from 1,000 to 900 won’t create meaningful change. Real transformation requires the courage to fundamentally rethink how work gets done.

For anyone who’s ever felt the soul-crushing weight of bureaucracy, Bayer’s radical reinvention offers hope. Maybe the path to innovation isn’t through better rules and processes, but through the courage to trust in human potential.

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 6, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Metrics, Stories & Examples

Here’s a head-scratcher when it comes to scaling innovation: What happens when your innovative product is a hit with customers, but you still fail spectacularly? Just ask the folks behind Smashmallow, the gourmet marshmallow company that went from sweet success to sticky situation faster than you can say “s’mores.”

The Recipe for Initial Success

Jon Sebastiani sold his premium jerky company Krave to Hershey for $240 million and thought he’d found his next billion-dollar idea in fancy French marshmallows. And initially, it looked like he had.

Smashmallow’s artisanal, flavor-packed treats weren’t just another fluffy, tasteless sugar puff – they created an entirely new snack category. Customers couldn’t get enough of their handcrafted, churro-dusted, chocolate-chip-studded clouds of happiness. The company hit $5 million in sales in its first year, doubled that the next, and was available in 15,000 stores nationwide in only its third year.

Sounds like a startup fairy tale, right? Right! If we’re talking about the original Brothers Grimm versions. Corporate innovators start taking notes.

The Candy-coated Vision

Sebastiani and his investors weren’t content with building a successful premium regional brand. They wanted to become the Kraft of craft marshmallows, scaling from artisanal to industrial without losing what made the product special. It’s a story that plays out in corporations every day: the pressure to turn every successful pilot into a billion-dollar business.

So, they invested. Big time.

They signed a contract with “an internationally respected builder of candy-making machines” to design and build a $3 million custom-built machine and another with a copacker to build an entirely new facility to accommodate the custom machine.

Bold visions require bold moves, and Sebastiani was a bold guy.

The Scale-up Meltdown

But boldness can’t overcome reality, and the custom machine couldn’t replicate the magic of handmade marshmallows. It couldn’t even make the marshmallows.

Starch dust created explosion hazards. Cinnamon wouldn’t stick. Workers couldn’t breathe through spice clouds. The handmade ethos of imperfect squares gave way to industrialized perfection. Each attempt to solve one problem created three more, like a game of confectionery whack-a-mole.

By 2022, Smashmallow was gone, leaving behind a cautionary tale about the gap between what customers value and what executives and investors want. The irony? They succeeded in their mission to disrupt the market – by 2028, the North American marshmallow market is projected to more than double its 2019 size, largely thanks to the premium category Smashmallow created. They just won’t be around to enjoy it.

A Bittersweet Paradox

For so many corporate innovators, this story hits close to home. How many promising projects died not because customers didn’t love them but because they couldn’t scale to “move the needle” for a multi-billion dollar corporation? A $15 million business might be a champagne-popping moment for an entrepreneur, but it barely registers as a rounding error on a Fortune 500 income statement.

This is the innovation paradox facing corporate innovators: The very pressure to go big or go home often destroys what makes an innovation special in the first place. It’s not enough to create something customers love – you must create something that can scale to satisfy the corporate appetite for growth.

Finding the Sweet Spot

The lesson isn’t that we should abandon ambitious scaling plans. Instead, we must be brutally honest about whether our drive for scale aligns with what makes our innovation valuable to customers. If it doesn’t, we must choose whether to scale back our ambitions (unlikely) or let go of our successful-but-small idea.

After all, not every marshmallow needs to be a mountain, but every mountain climber (that’s you) needs a mountain.

by Robyn Bolton | Dec 4, 2024 | Innovation, Just for Fun, Leadership, Metrics, Uncategorized

Last week, InnoLead published a collection of 11 articles describing the root causes and remedies for killers of innovation in large organizations. Every single article is worth a read as they’re all written by experts and practitioners whose work I admire.

I was also inspired.

In the spirit of the hustle and bustle of the holiday season, I gave into temptation, added my own failure mode, and decided to have a bit of fun.

The 12 Killers of Innovation

(Inspired by the 12 Days of Christmas yet relevant year-round)

On the twelfth day of innovating, management gave to me:

12 leaders short-term planning

11 long projects dragging

10 cultures resisting

9 decisions made too quickly

8 competing visions

7 goals left unclear

6 startups mistrusted

5 poorly defined risks

4 rigid structures

3 funding black holes

2 teams under-staffed

And a bureaucracy too entrenched to change

Want to write a happier song?

Each of the innovation killers can be fended off with enough planning, collaboration, and commitment. To learn how, check out the articles:

12 leaders short-term planning – Why Innovation is a Leadership Problem by Robyn Bolton, MileZero

11 long projects dragging – Failing Slow by Clay Maxwell, Peer Insight

10 cultures resisting – How to Innovate When Resistance is Everywhere by Trevor Anulewicz, NTT DATA

9 decisions made too quickly – Red Light, Green Light by Doug Williams, SmartOrg Inc.

8 competing visions – The Five Most Common Innovation Failure Modes by Parker Lee, Territory Global

7 goals left unclear – Mitigating Common Failure Modes by Jim Bodio, BRI Associates

6 startups mistrusted – Developing a New Corporate Innovation Model by Satish Rao, Newlab

5 poorly defined risks – Strategic Innovation is too Scary by Gina O’Connor, Babson College

4 rigid structures – Corporate Innovation is Dead by Ryan Larcom, High Alpha Innovation

3 funding black holes – Failure Modes by Jake Miller, The Engineered Innovation Group

2 teams under-staffed – Why Innovation Teams Fail by Jacob Dutton, Future Foundry

And a bureaucracy too entrenched to change – Building Resilient Teams by Frank Henningsen, HYPE Innovation

How are you going to make sure that you receive gifts and not coal this year for all your innovation work?