by Robyn Bolton | Apr 1, 2025 | Leadership, Stories & Examples, Strategy

If you’re leading a legacy business through uncertainty, pay attention. When The Cut asked, “Can Simon & Schuster Become the A24 of Books?” I expected puff-piece PR. What I read was a quiet masterclass in business transformation—delivered in three deceptively casual quotes from Sean Manning, Simon & Schuster’s new CEO. He’s trying to transform a dinosaur into a disruptor and lays out a leadership playbook worth stealing.

Seventy-four percent of corporate transformations fail, according to BCG. So why should we believe this one might be different? Because every now and then, someone in a legacy industry goes beyond memorable soundbites and actually makes moves. Manning’s early actions—and the thinking behind them—hint that this is a transformation worth paying attention to.

“A lot of what the publishing industry does is just speaking to the converted.”

When Manning says this, he’s not just throwing shade—he’s naming a common and systemic failure. While publishing execs bemoan declining readership, they keep targeting the same demographic that’s been buying hardcovers for decades.

Sound familiar?

Every legacy industry does this. It’s easier—and more immediately profitable—to sell to those who already believe. The ROI is better. The risk is lower. And that’s precisely how disruption takes root.

As Clayton Christensen warned in The Innovator’s Dilemma, established players obsess over their best customers and ignore emerging ones—until it’s too late. They fear that reaching the unconverted dilutes focus or stretches resources. But that thinking is wrong. Even in a world of finite resources, you can’t afford to pick one or the other. Transformation, heck, even survival, requires both.

“We’re essentially an entertainment company with books at the center.”

Be still my heart. A CEO who defines his company by the Job(to be Done) it performs in people’s lives? Swoon.

This is another key to avoiding disruption – don’t define yourself by your product or industry. Define yourself by the value you create for customers.

Executives love repeating that “railroads went out of business because they thought their business was railroads.” But ask those same executives what business they’re in, and they’ll immediately box themselves into a list of products or industry classifications or some vague platitude about being in the “people business” that gets conveniently shelved when business gets bumpy.

When you define yourself by the Job you do for your customers, you quickly discover more growth opportunities you could pursue. New channels. New products. New partnerships. You’re out of the box —and ready to grow.

“The worry is that we can’t afford to fail. But if we don’t try to do something, we’re really screwed.”

It’s easy to calculate the cost of trying and failing. You have the literal receipts. It’s nearly impossible to calculate the cost of not trying. That’s why large organizations sit on the sidelines and let startups take the risks.

But there IS a cost to waiting. You see it in the market share lost to new entrants and the skyrocketing valuations of successful startups. The problem? That information comes too late to do anything about it.

Transformation isn’t just about ideas. It’s about choosing action over analysis. Or, as Manning put it, “Let’s try this and see what happens.”

Walking the Talk

Quotable leadership is cute. Transformation leadership is concrete. Manning’s doing more than talking—he’s breaking industry norms.

Less than six months into his tenure as CEO, he announced that Simon & Schuster would no longer require blurbs—those back-of-jacket endorsements that favor the well-connected. He greenlit a web series, Bookstore Blitz, and showed up at tapings. And he’s reframing what publishing can be, not just what it’s always been.

The journey from dinosaur to disruptor is long, messy, and uncertain. But less than a year into the job, Manning is walking in the right direction.

Are you?

by Robyn Bolton | Mar 11, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Stories & Examples

Ideas and insights can emerge from the most unexpected places. My mom was a preschool teacher, and I often say that I learned everything I needed to know about managing people by watching her wrangle four-year-olds. But it only recently occurred to me that the most valuable business growth lessons came from my thoroughly unremarkable years playing the flute in middle school.

6th Grade: Following the Manual and Falling Flat

Sixth grade was momentous for many reasons, one being that that was when students could choose an instrument and join the school band. I chose the flute because my friends did, and there was a rumor that clarinets gave you buck teeth—I had enough orthodontic issues already.

Each week, our “jill of all trades” teacher gathered the flutists together and guided us through the instructional book until we could play a passable version of Yankee Doodle. I practiced daily, following the book and playing the notes, but the music was lifeless, and I was bored.

7th Grade: Finding Context and Direction

In seventh grade, we moved to full band rehearsals with a new teacher trained to lead an entire band (he was also deaf in one ear, which was, I think, a better qualification for the job than his degree). Hearing all the instruments together made the music more interesting and I was more motivated to practice because I understood how my part played in the whole. But I was still a very average flutist.

To help me improve, my parents got me a private flute teacher. Once a week, Mom drove me to my flute teacher’s house for one-on-one tutoring. She corrected mistakes when I made them, showed me tips and tricks to play faster and breathe deeper, and selected music I enjoyed playing. With her help, I became an above-average flutist.

Post-Grad: 5 Business Truths from Band Class

I stopped playing in the 12th grade. Despite everyone’s efforts, I was never exceptional—I didn’t care enough to do the work required.

Looking back, I realized that my mediocrity taught me five crucial lessons that had nothing to do with music:

- Don’t do something just because everyone else is. I chose the flute because my friends did. I didn’t choose my path but followed others—that’s why the music was lifeless.

- Following the instruction manual is worse than doing nothing. You can’t learn an instrument from a book. Are you sharp or flat? Too fast or slow? You don’t know, but others do (but don’t say anything).

- Part of a person is better than all of a book. Though spread thin, the time my teachers spent with each instrumental section was the difference between technically correct noise and tolerable music.

- A dedicated teacher beats a distracted one. Having someone beside me meant no mistake went uncorrected and no triumph unrecognized. She knew my abilities and found music that stretched me without causing frustration.

- If you don’t want to do what’s required, be honest about it. I stopped wanting to play the flute in 10th grade but kept going because it was easier to maintain the status quo. In hindsight, a lot of time, money, and effort would have been saved if I stopped playing when I stopped caring.

The Executive Orchestra: What Grade Are You In?

How many executives remain in sixth grade—following management fads because of FOMO, buying books, handing them out, and expecting magic? And, when that fails, hiring someone to do the work for them and wondering why the music stops when the contract ends?

How many progress to seventh grade, finding someone who can teach, correct, and celebrate their teams as they build new capabilities?

How do what I should have done in 10th grade and be honest about what they are and aren’t willing to do, spending time and resources on priorities rather than maintaining an image?

More importantly, what grade are you in?

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 22, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Metrics, Stories & Examples

“Consider this question: If workers are hobbled by 1,000 rules, does it make a meaningful difference to reduce them to only 900?”

The answer is No. In fact, this is precisely why most attempts at fighting bureaucracy fail – and why true transformation requires starting completely fresh.

Bill Anderson, CEO of Bayer, knows this and isn’t afraid to admit it. When he took the helm in June 2023, he discovered a company paralyzed by bureaucracy. Instead of trying to optimize the system, he looked at the company’s “1,362 pages” of employee rules and knew the entire structure needed to change.

Breaking the Stranglehold

As Anderson stated in Fortune, “There was a time for hierarchical, command-and-control organizations – the 19th century, to be exact, when many workers were illiterate, information traveled at a snail’s pace, and strict adherence to rules offered the competitive advantage of reliability.”

The modern reality is different. Today’s Bayer employs highly skilled experts, operates at digital speed, and competes in markets where, as Anderson observes, “the most reliable companies are the most dynamic.”

The challenge wasn’t just the encyclopedic rulebook. The organization’s “12 levels of hierarchy” created what Anderson called “unnecessary distance between our teams, our customers, and our products.” In today’s innovation-driven market, this industrial-age structure threatened the company’s future.

Unleashing Innovation

Anderson’s solution? “Dynamic Shared Ownership” – a radical model that puts 95% of decision-making in the hands of the people actually doing the work. Instead of annual budgets and endless approvals, self-directed teams work in 90-day sprints with the autonomy to make real-time decisions.

The results are already showing. Take Vividion, Bayer’s independently operated subsidiary. Operating in small, autonomous teams, they went from FDA approval to first patient dosing in just six weeks. They’re now on track to produce one or two new drug candidates for clinical testing every year.

Speed Becomes Reality

The impact extends across the organization. Bayer’s scientists have transformed their plant breeding process, reducing cycles from “five years down to merely four months.”

In the consumer health division, teams have accelerated their development timelines significantly, reducing product launch schedules “by up to nine months” in Asia. Within their first two months under the new system, these teams generated millions in additional value.

While financial markets remain uncertain about this transformation, one crucial metric suggests it’s working: employee retention has improved. The scientists, researchers, and product developers – the people doing the innovative work – are showing their confidence in this dramatic shift toward autonomous operation.

Why This Matters & What to do Next

For most of us, the question isn’t whether our organization has too much bureaucracy – it almost certainly does. The question is: what are you going to do about it?

Try this – Create a small, autonomous team with a 90-day mission. Give them real decision-making power and see what they can accomplish when freed from bureaucratic constraints.

Remember Anderson’s key insight: reducing rules from 1,000 to 900 won’t create meaningful change. Real transformation requires the courage to fundamentally rethink how work gets done.

For anyone who’s ever felt the soul-crushing weight of bureaucracy, Bayer’s radical reinvention offers hope. Maybe the path to innovation isn’t through better rules and processes, but through the courage to trust in human potential.

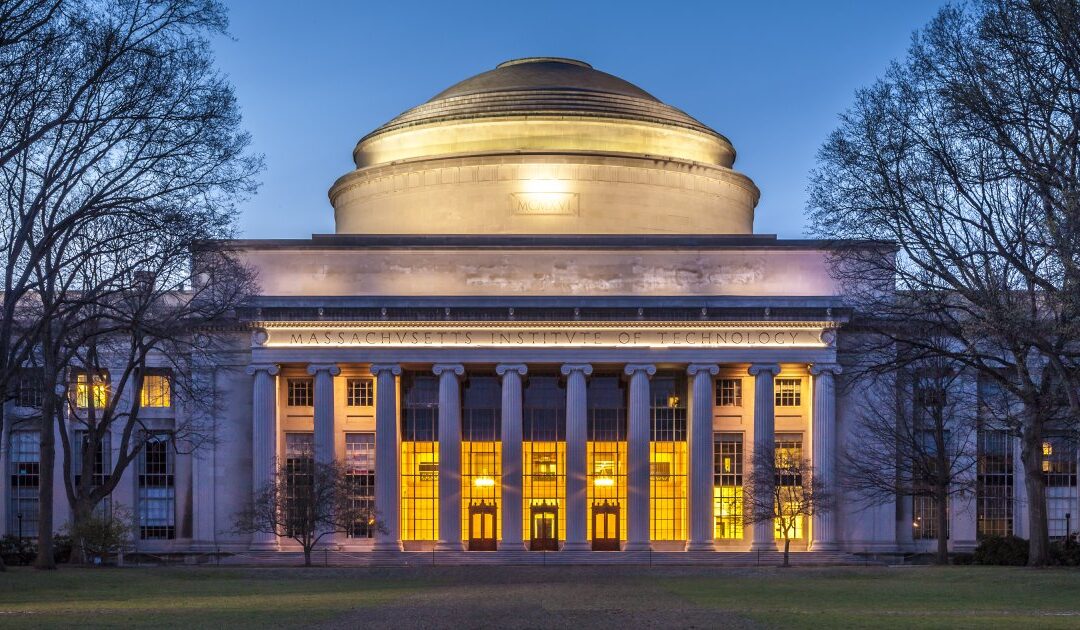

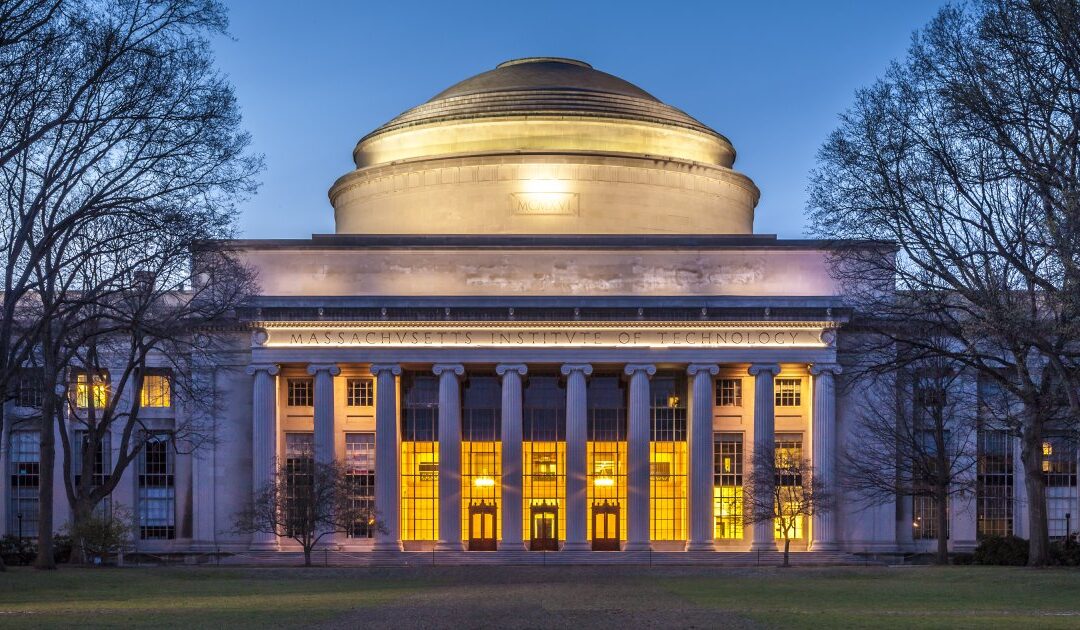

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 15, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Stories & Examples

I firmly believe that there are certain things in life that you automatically say Yes to. You do not ask questions or pause to consider context. You simply say Yes:

- Painkillers after a medical procedure

- Warm blankets

- The opportunity to listen to brilliant people talk about things that fascinate them.

So, when asked if I would like to attend an Executive Briefing curated by MIT’s Industrial Liaison Program, I did not ask questions or pause to check my calendar. I simply said Yes.

I’m extremely happy that I did because what I heard blew my mind.

Lean is the enemy of learning

When Ben Armstrong, Executive Director of MIT’s Industrial Performance Center and Co-Lead of the Work of the Future Initiative, said, “To produce something new, you need to create a lot of waste,” I nearly lept out of my chair, raised my arms, and shouted “Amen brother!”

He went on to tell the story of a meeting between Elon Musk and Toyota executives shortly after Musk became CEO. Toyota executives marveled at how quickly Tesla could build an EV and asked Musk for his secret. Musk gestured around the factory floor at all the abandoned hunks of metal and partially built cars and explained that, unlike Toyota, which prided itself on being lean and minimizing waste, Tesla engineers focused on learning – and waste is a required part of the process.

We decide with our hearts and justify with our heads – even when leasing office space

John E. Fernández, Director of MIT’s Environmental Solutions Initiative, shared an unexpected insight about selling sustainable buildings effectively. Instead of hard numbers around water and energy cost savings, what convinces companies to pay the premium for Net Zero environments is prestige. The bragging rights of being a tenant in Winthrop Center, Boston’s first-ever Passive House office building, gave developers a meaningful point of differentiation and justified higher-than-market-rate rents to future tenants like McKinsey and M&T Bank.

49% of companies are Silos and Spaghetti

I did a hard eye roll when I saw Digital Transformation on the agenda. But Stephanie Woerner, Principal Research Scientists and Executive Director for MIT’s Center for Information Systems Research, proved me wrong by explaining that Digital Transformation requires operational excellence and customer-focused innovation.

Her research reveals that while 26% of companies have evolved to manage both innovation and operations, operate with agility, and deliver great customer experiences, nearly half of companies are stuck operating in silos and throwing spaghetti against the wall. These “silo and spaghetti companies” are often product companies rife with complex systems and processes that require and reward individual heroics to make progress.

What seems like the safest option is the riskiest

How did 26% of companies transform while the rest stayed stuck or made little progress? The path forward isn’t what you’d expect. Companies that go all-in on operational excellence or customer innovation struggle to shift focus and work in the other half of the equation. But doing a little bit of each is even more risky because the companies often wait for results from one step before taking the next. The result is a never-ending transformation slog that is eventually abandoned.

Academia is full of random factoids

They’re not random to the academics, but for us civilians, they’re mainly helpful for trivia night:

- 50% of US robots are used in the automotive industry

- <20% of manufacturing job descriptions require digital skills (yes, that includes MS Office)

- Data centers will account for 8-21% of global energy demand by 2030

- Energy is 10% of the cost of running a data center but 90% of the cost of mining bitcoin

- Cities take up 3% of the earth’s surface, contain 33% of the population, account for 70% of global electricity consumption, and are responsible for 75% of CO2 emissions

Why say Yes

When brilliant people talk about things they find fascinating, it’s often because those things challenge conventional wisdom. The tension between lean efficiency and innovative learning, the role of emotion in business decisions, and the risks of playing it too safe all point to a fascinating truth: sometimes the most counterintuitive path forward is the most successful.

How have you seen this play out in your work?

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 6, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Metrics, Stories & Examples

Here’s a head-scratcher when it comes to scaling innovation: What happens when your innovative product is a hit with customers, but you still fail spectacularly? Just ask the folks behind Smashmallow, the gourmet marshmallow company that went from sweet success to sticky situation faster than you can say “s’mores.”

The Recipe for Initial Success

Jon Sebastiani sold his premium jerky company Krave to Hershey for $240 million and thought he’d found his next billion-dollar idea in fancy French marshmallows. And initially, it looked like he had.

Smashmallow’s artisanal, flavor-packed treats weren’t just another fluffy, tasteless sugar puff – they created an entirely new snack category. Customers couldn’t get enough of their handcrafted, churro-dusted, chocolate-chip-studded clouds of happiness. The company hit $5 million in sales in its first year, doubled that the next, and was available in 15,000 stores nationwide in only its third year.

Sounds like a startup fairy tale, right? Right! If we’re talking about the original Brothers Grimm versions. Corporate innovators start taking notes.

The Candy-coated Vision

Sebastiani and his investors weren’t content with building a successful premium regional brand. They wanted to become the Kraft of craft marshmallows, scaling from artisanal to industrial without losing what made the product special. It’s a story that plays out in corporations every day: the pressure to turn every successful pilot into a billion-dollar business.

So, they invested. Big time.

They signed a contract with “an internationally respected builder of candy-making machines” to design and build a $3 million custom-built machine and another with a copacker to build an entirely new facility to accommodate the custom machine.

Bold visions require bold moves, and Sebastiani was a bold guy.

The Scale-up Meltdown

But boldness can’t overcome reality, and the custom machine couldn’t replicate the magic of handmade marshmallows. It couldn’t even make the marshmallows.

Starch dust created explosion hazards. Cinnamon wouldn’t stick. Workers couldn’t breathe through spice clouds. The handmade ethos of imperfect squares gave way to industrialized perfection. Each attempt to solve one problem created three more, like a game of confectionery whack-a-mole.

By 2022, Smashmallow was gone, leaving behind a cautionary tale about the gap between what customers value and what executives and investors want. The irony? They succeeded in their mission to disrupt the market – by 2028, the North American marshmallow market is projected to more than double its 2019 size, largely thanks to the premium category Smashmallow created. They just won’t be around to enjoy it.

A Bittersweet Paradox

For so many corporate innovators, this story hits close to home. How many promising projects died not because customers didn’t love them but because they couldn’t scale to “move the needle” for a multi-billion dollar corporation? A $15 million business might be a champagne-popping moment for an entrepreneur, but it barely registers as a rounding error on a Fortune 500 income statement.

This is the innovation paradox facing corporate innovators: The very pressure to go big or go home often destroys what makes an innovation special in the first place. It’s not enough to create something customers love – you must create something that can scale to satisfy the corporate appetite for growth.

Finding the Sweet Spot

The lesson isn’t that we should abandon ambitious scaling plans. Instead, we must be brutally honest about whether our drive for scale aligns with what makes our innovation valuable to customers. If it doesn’t, we must choose whether to scale back our ambitions (unlikely) or let go of our successful-but-small idea.

After all, not every marshmallow needs to be a mountain, but every mountain climber (that’s you) needs a mountain.

by Robyn Bolton | Nov 12, 2024 | Customer Centricity, Leadership, Stories & Examples

“Now I know why our researchers are so sad.”

Teaching at The Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt) offers a unique perspective. By day, I engage with seasoned business professionals. By night, I interact with budding designers and artists, each group bringing vastly different experiences to the table.

Customer-centricity is the hill I will die on…

In my Product Innovation Lab course, students learn the innovation process and work in small teams to apply those lessons to the products they create.

We spend the first quarter of the course to problem-finding. It’s excruciating for everyone. Like their counterparts in business and engineering, they’re bursting with ideas, and they hate being slowed down. Despite data proving that poor product-market fit a leading cause of start-up failure and that 54% of innovations launched by big companies fail to reach $1M in sales (a paltry number given the scale of surveyed companies), they’re convinced their ideas are flawless.

We spend two weeks exploring Jobs to be Done and practicing interviewing techniques. But their first conversations sound more like interrogations than anything we did in class.

They return from their interviews and share what they learned. After each insight, I ask, “Why is that?” or “Why is that important?

Amazingly, they have answers.

While their first conversations were interrogations, once the nervousness fades, they remember their training, engage in conversations, and discover surprising and wonderful answers.

Yet the still prioritize the answers to “What” over answers to “Why?”

…Because it’s the hill that will kill me.

Every year, this cycle repeats. This year, I finally asked why, after weeks of learning that the answers to What questions are almost always wrong and Why questions are the only path to the right answers (and differentiated solutions with a sustainable competitive advantage), why do they still prioritize the What answers?

The answer was a dagger to my heart.

“That’s what the boss wants to know,” a student explained. “Bosses just want to know what we need to build so they can tell engineering what to make. They don’t care why we should make it or whether it’s different. In fact, it’s better if it’s not different.”

I tried to stay professional, but there was definitely a sarcastic tone when I asked how that was working.

“We haven’t launched anything in 18 months because no one likes what we build. We spend months on prototypes, show them to users, and they hate it. Then, when we ask the researchers to do more research because their last insights were wrong, they get all cra….OOOOHHHHHHHH…..”

(insert clouds parting, beams of sunlight shining down, and a choir of angels here)

“That’s why the researchers are so sad all the time! They always try to tell us the “Whys” behind the “Whats” but no one wants to hear it. We just want to know what to build to get to work. But we could create something people love if we understood why today’s things don’t work!”

Honestly, I didn’t know whether to drop the mic in triumph or flip the table in rage.

Ignorance may be bliss but obsolesce is not

It’s easy to ignore customers.

To send them surveys with pre-approved answers choices that can be quickly analyzed and neatly presented to management. To build exactly what customers tell you to build, even though you’re the expert on what’s possible and they only know what’s needed.

It’s easy to point to the surveys and prototypes and claim you are customer-centric. If only the customers would cooperate.

It’s much harder to listen to customers. To ask questions, listen to answers you don’t want to hear, and repeat those answers to more powerful people who want to hear them even less. To have the courage to share rough prototypes and to take the time to be curious when customers call them ugly.

So, if you want to be happy, keep pretending to care about your customers.

Pretty soon, you won’t have any left to bother you.