by Robyn Bolton | Jan 4, 2022 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

Before we go any further, I need to be clear that I absolutely, totally, and completely believe in Jobs to be Done. In fact, more than once, I have uttered the words, “Jobs to be Done is a hill I will die on.”

Which means that I died a little inside when a client recently said to me,

“Jobs to be Done is amazing. ‘Jobs to be Done’ sucks.”

He’s right (as much as it kills me to admit that).

In an academic setting, the term makes perfect sense.

I understand where the term comes from and applaud the logic and clarity of the analogy at its core. Just as a company hires a person for a task or set of functions (a job), a person “hires” a product or service because they have a problem to solve or progress they need to make. They have a Job to be Done.

Managers and executives who work with me to learn Jobs to be Done and how to apply it quickly grasp the concept. After just one-hour, they can re-tell and explain the Milkshake story, identify functional/emotional/social jobs in role plays, and swear that the approach completely changes how they see and think about their business.

In the real world, the term is profoundly confusing.

Then the managers and executives, believing so strongly in its ability to transform the business, decide to roll it out to the organization. They talk about it, send articles about it, and train everyone to apply it in customer interviews. With great excitement, everyone from employees to senior leaders fan out to talk to customers, take copious notes, discuss insights with their teams, and happily declare that their customers’ Jobs to be Done are to buy the company’s products.

Here’s a quick (and entirely fictional) example:

- Chocolate Chip Cookie Company (CCCC): Hello, Ms. Customer. We want to learn more about your snacking habits. When you snack and why, what you like to snack on and why, stuff like that.

- Customer: Great! I love to snack on chocolate chip cookies, but the store-bought ones are expensive, and they’re filled with preservatives, and I’m trying to be healthier. I’d make my own, but I don’t have time.

CCCC returns to the office and declares that the customer’s Job to be Done is to buy cheap all-natural cookies from a store.

Ummm, no. Not even close.

The customer’s Jobs to be Done are to be healthy, manage her money, save time, and feel good about what she eats. CCCC’s job (literally, the company’s reason for business) is to make cookies that customers want to buy.

What CCCC identified as a customer Job to be Done is the company’s job (business). In other words, it’s a solution.

Why the confusion?

In the real world, people already have precise definitions of “job” in their heads. They have a job (role). They have a job to do (responsibilities, deliverables). Their colleagues have jobs (roles and responsibilities). They have job openings (hiring needs).

By assigning a new meaning to the word “job,” we’re not only asking people to change how they think and talk, but we’re also asking them to adopt an entirely new understanding of and use for a common word.

Imagine being told that “orange” means both a color and a cooking technique. It makes the brain hurt.

What’s the solution?

I don’t know. But here’s what I’ve tried.

- Problem

- Pro: It’s part of the definition of a Job to be Done, and we all know what a problem is

- Con: It focuses customer conversations on existing pain points and sets a negative tone in interviews, making it challenging to discover solutions that delight the customer and, as a result, could inform how the problem is solved.

- Need

- Pro: It’s the OG of consumer research, a term we all know and use

- Con: It anchors customer conversations in functional Jobs to be Done and makes it difficult to surface the emotional and social Jobs that drive decisions and behavior.

- Customer Job to be Done

- Pro: Uses the original term while being VERY clear that the focus is on the customer

- Con: It’s a lot to say and even more to type, and people still fall back into their traditional definitions and use of the term job

What have you tried? What are your suggestions?

by Robyn Bolton | Dec 8, 2021 | Tips, Tricks, & Tools

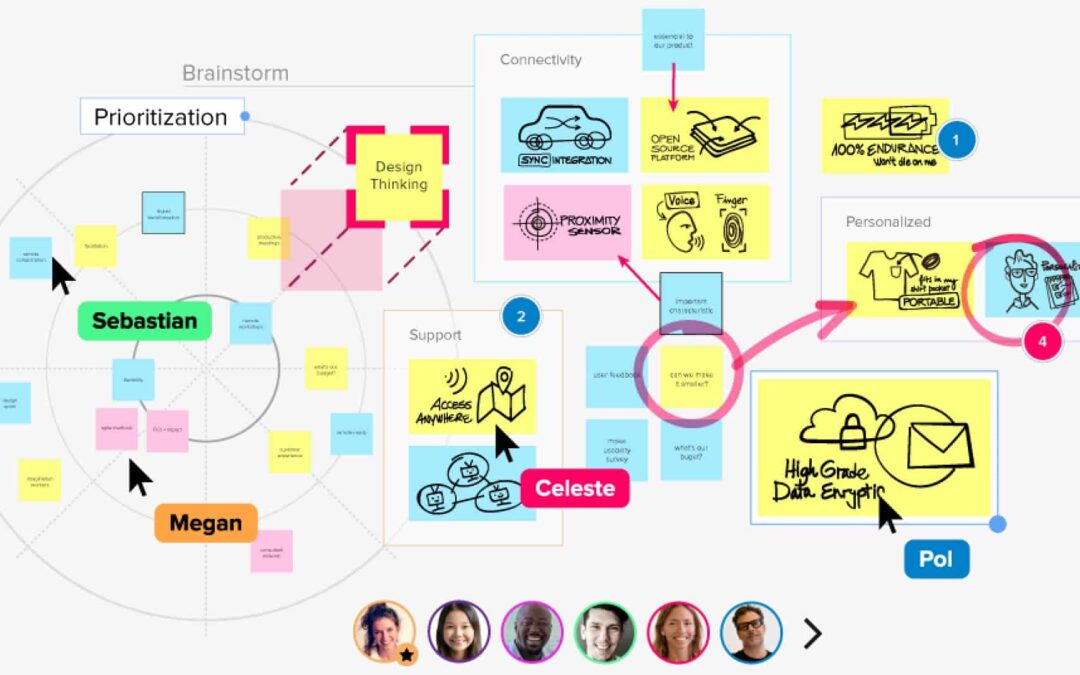

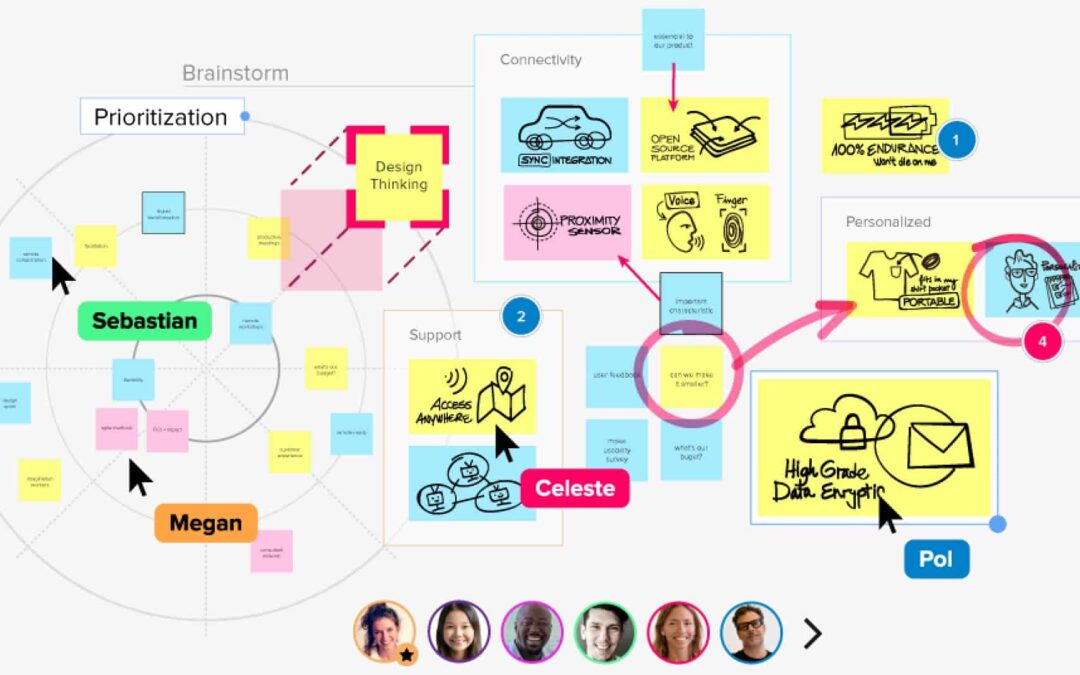

Over the past 987,460 days of forced WFH, I’ve participated in several virtual ideations.

A few weeks ago, my turn to facilitate arrived. And, after four 4-hour sessions spread over two weeks, I can confidently declare this:

Virtual Ideation sucks.

We knew the experience wouldn’t be the same as an in-person session, so we did everything to adapt. At the end of each session, we asked participants to share their Rose/Bud/Thorn feedback. Between sessions, a smaller group met to review the feedback, reflect on our experiences, and make adjustments for the next session. We fixed 90% of the Thorns between sessions 1 and 2, and we hit our groove by session three.

But virtual Ideation still sucks.

There is simply no substitute for the energetic buzz of a room full of creators freed from the constraints of reality and excitedly imagining what could be. There is no substitute for the side conversations over caffeine and sugar where two or three innovators connect disparate dots and have an A-Ha! Moment. There is absolutely no substitute for the satisfaction that comes from stepping back and staring at a wall of ideas and the confidence that the answer is in there somewhere.

But, with Omicron and more companies realizing the hybrid work is the new reality, not a temporary stopgap, virtual ideation sessions are here to stay.

So how can we make virtual ideation sessions suck less?

Plan sprints, not marathons.

- What we did: We cut the ideation session down from the typical 8-hour day to four hours, and instead of trying to ideate on multiple topics in a single session, we had a single topic for each session. But the sessions were still too long to keep people engaged but too short to allow true reflection and building on ideas.

- What we learned: In a virtual setting,ideation sessions are a task, not an experience. Gathering people together for a day or two made lots of sense for logistical (usually held offsite, make participants less accessible to daily demands, reduce the cost of external facilitators) and experiential (enable focus, shift mindsets, get into the flow) reasons. But a virtual environment eliminates the logistical rationale for daylong sessions. It can’t deliver the experiential benefits because we can’t get away from the constant pinging of email, Slack, and text notifications.

- What we would do differently: Instead ofa four-hour session, I would do four one-hour sessions. Yes, it will take more days, but participants will be more focused on the task and more able to stay in the creative mindset (once you get them there). Plus, it has the added benefits of engaging more participants (looking at you, fellow introverts!) and giving people time to reflect and build on ideas.

Acknowledge that the practice and experience will be different

- What we did: We started the sessions by acknowledging that things would feel different, the experience would be far from seamless, and that we wanted quality over quantity. But we didn’t recognize participants’ feelings and expectations, and, as a result, the gaps between their hopes and their reality didn’t diminish.

- What we learned: Even though people know that the experience of a virtual ideation session is different from an in-person one, they still hope that it will be the same. This creates a challenge that participants will inevitably judge the experience not against their rational expectations but against their hopeful, emotional ones. And it will always come up short.

- What we would do differently: Start the session by clearly stating that the experience will be and feel different. Acknowledge that, for many, it won’t have the buzz or the rush of an in-person session. Admit that things will be more clunky because you’re relying on technology rather than your hands and feet to make things happen. Ask for their patience, support, and help to make the session and their experience of it as successful as possible. Then clearly define what success looks like.

Start with FUN!

- What we did: I hate icebreakers, “mandatory fun,” and forced group silliness. So, we didn’t do any of that in the first ideation session. Instead, we dove right into content, grounding people in the insights developed in the previous phase and introducing them to the resulting stimuli (personas, journey maps, analogies).

- What we learned: We were so task-focused that people didn’t have time to shake off their day-to-day reality, connect with the information, develop empathy for the customer, and allow themselves to be creative.

- What we did do differently: The second session started with FUN! but rather than a random icebreaker or silly exercise, we asked a question that required personal sharing and was relevant to the session’s topic. For example, if the session’s topic was “How might we create a more inspiring experience for members?” we asked participants to share their most inspiring experience.

By asking a personal question, people’s mindsets become more positive and open while they get more comfortable sharing and more curious about their fellow participants. By asking a relevant question, participants build empathy for the customer they are designing for, instantly build a library of experiences and analogies to draw from, and see possibilities beyond their day-to-day realities.

The irony of it all

What’s ironic is that, as I reflect on these lessons, they’re all things that I knew to be important, but I hadn’t yet experienced their importance.

Learn from my experience. Make these changes in your next ideation session.

What are your experiences? What have you learned? What can we learn from you?

by Robyn Bolton | Nov 20, 2021 | Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

Everyone knows about brainstorms but did you know there are three other types of storms that can blow you to your innovation destination?

Questionstorms

First introduced in The Innovator’s DNA, these storms happen at the start of an innovation effort and seek to surface all the assumptions, expectations, concerns, and actual questions currently locked in individuals’ brains.

The value of this session is that it makes the implicit explicit, removes hidden agendas, eliminates guessing games, and establishes a culture of curiosity, exploration, and learning versus demands and fear.

You run Questionstorms just like brainstorms – give everyone 3-5 minutes to silently write a long list of thoughts. Then, give everyone another 3-5 minutes to turn each thought into a question and write the question on a sticky note. For example, “We need to realize $250M revenue in Year 3 to make this work” becomes “How might we design and run an innovation function that generates $250M in Year 3?” Then, each person reads their sticky notes to the group before placing them on a wall. The goal is to ask 50 questions before you start grouping and prioritizing.

Intuition-storms

I first learned about this storm from IDEO and am genuinely surprised by how effectively they re-energize teams and propel the work forward. These storms happen after the first phase of a project, usually the research phase.

An Intuition-storm’s value comes from its ability to pull the team out of the minutiae of the previous weeks and months of work and back up to seeing the big picture. In the process, they rapidly synthesize insights that may have gotten lost in the more traditional left-brained approach of gathering and summarizing details.

Again, just like brainstorms, start by posing the big question that the project intends to answer, then give people 3-5 minutes to write down their answers. Too much time and they may dig into documents and details, too little time and you’ll get recency bias in the responses. Then go around the room and share. Once everyone has shared, discuss the elements in common and the unique ones. Be clear that this isn’t about getting to THE answer, but about tapping into the full of everyone’s experience, expertise, and wisdom.

Brainstorms

By now, we all know what it means to brainstorm, and we’ve all probably been part of one or two brainstorming sessions. But do you know where it all started?

In the mid-nineteenth century, “brainstorm” was a colloquial term for “fit of acute delirious mania; sudden dethronement of reason and will under the stress of strong emotion, usually accompanied by manifestations of violence.” Not exactly the type of thing most businesspeople aim for.

However, in 1939, advertising executive Alex F. Osborn got so frustrated with his employees’ ability to generate creative ideas for ad campaigns that he developed a new approach dubbed “organized ideation.” This approach, later renamed to “brainstorm” by his employees, was governed by four rules:

- Go for quantity

- Withhold criticism

- Welcome wild ideas

- Combine and improve ideas

While the methods and tools for brainstorming have evolved over the past 80+ years, it’s a testament to Osborn’s approach that the rules have not.

Assumption-storms

Assumption-storms are rooted in the Discovery Driven Planning approach introduced by Rita Gunther-McGrath. These storms should occur as soon as you’ve picked the top 2-3 ideas from brainstorming that you want to pursue

By forcing the team to acknowledge that there are more unknowns than knowns at this point in the process and to share their assumptions and questions, Assumption-storms enable the team to quickly identify and test the most critical assumptions. This process of rapid testing of individual assumptions ensures that if a “deal-killer” assumption is wrong, the project is quickly killed and a new one started.

To Assumption-storm, gather your team around the idea(s) to be pursued and list all the things you think you know but can’t prove beyond a shadow of a doubt AND all the things you don’t know. Then rate each item (assumption) from High to Low based on how confident you are that the assumption is true and the negative impact to the idea if the assumption is wrong.

Because we all tend to be overconfident in our own knowledge, I like to base the High/Medium/Low scale for confidence based on what you would bet. High confidence means you’re willing to bet your annual salary, Medium confidence means you’ll bet your next paycheck, and no confidence means you bet a cup of tea.

Once assessed for confidence and impact, the assumptions with Low Confidence and High Impact are identified as deal-killers, and you can start to develop the experiments you’ll run to help you build confidence (or kill the idea) in the next 90-days.

Storms are a-brewin.’

And that’s a good thing. As you progress through your innovation efforts, you’ll face many storms. Some are damaging and unexpected. Luckily, these four can not only be planned, they also propel you forward.

by Robyn Bolton | Nov 12, 2021 | Innovation, Leadership, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

“We are not lost. I know exactly where we are. Granted, it’s not where we want to be. Where we want to be is over there somewhere. I just need a moment to figure out how we get there.”

– Me to my husband every time we go to a new city and I convince him to go on a walk.

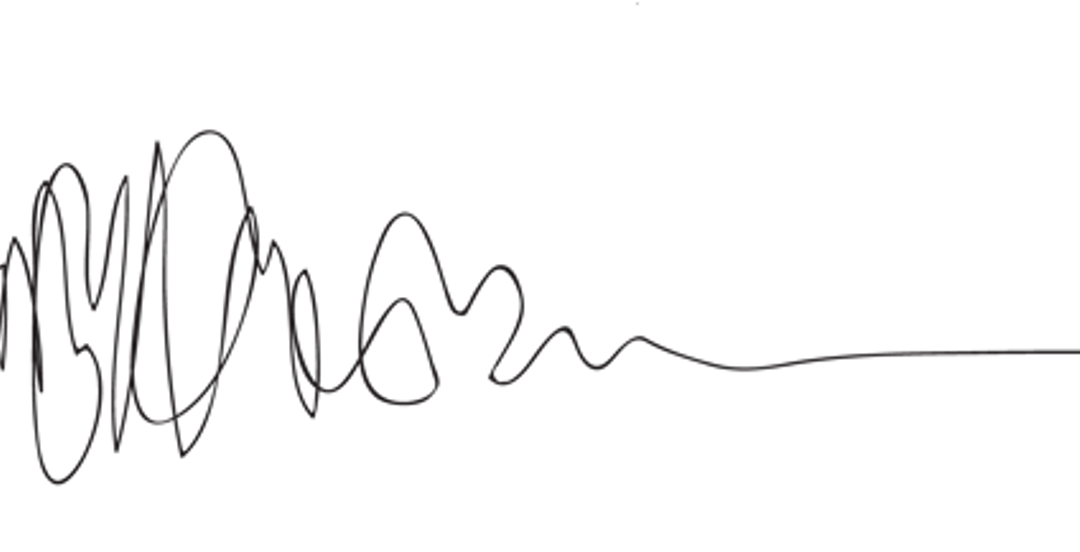

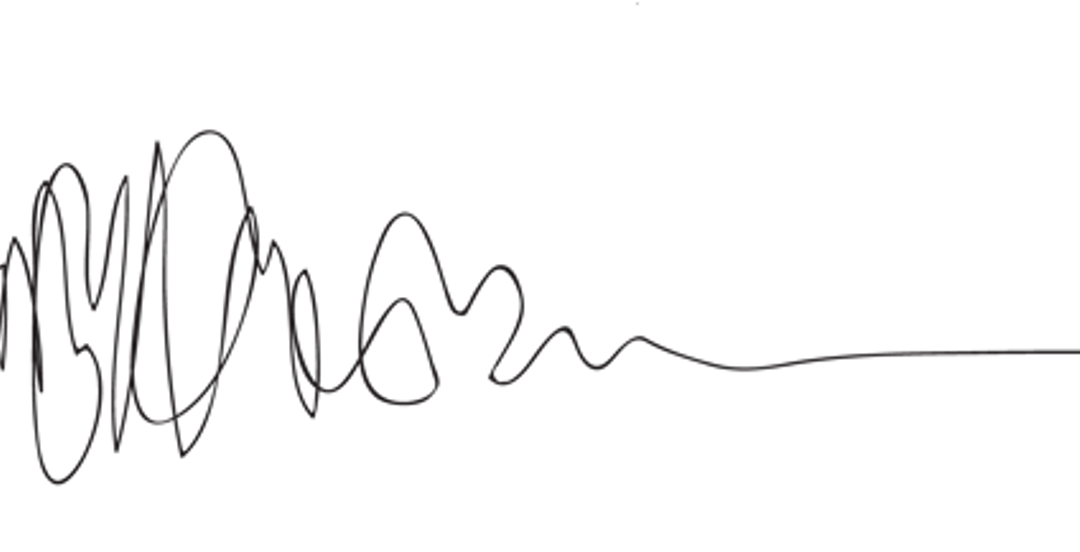

The Big Squiggly

Last week, the 13th class of Driving Intrapreneurship graduated and, as always, I was tremendously proud of the executives who, in the span of 8 short weeks, went from identifying a problem to writing an innovation business plan to secure funding and resources to continue their work.

One of the things we talk about constantly in the course is “The Big Squiggly” – a simple line drawing that starts off as a big, knotty, crumpled, chaotic mess before eventually sorting itself out and turning int a clean and simple straight line.

We spend most of the 8 weeks in The Big Squiggly and it’s even more uncomfortable and stressful than people imagine it will be when I first introduce the concept. But as the weeks go on, they get a little more comfortable and, by graduation, the mere mention of The Big Squiggly elicit knowing nods and confident smiles.

What To Do When You’re In The Big Squiggly

Innovators live in The Big Squiggly. Some of us love it there and some of us endure it because really, all we want to do, is bring order to chaos. Most of us in The Big Squiggly are like my students – uncomfortable at best and deeply stressed at worst.

In fact, being in The Big Squiggly can feel like being in the middle of a crisis.

Interestingly, they way innovators work through The Big Squiggly is very very similar to how leaders are taught to manage crises. Here is the 6-step approach that Harvard Professor Dutch Leonard teaches in his Crisis Management for Leaders course:

- Establish a team and process to identify, understand, and reframe issues

- Assemble a team with diverse perspectives

- Engage in iterative, agile problem-solving

- Create conditions (facilitated deliberation, diversity, psychological safety, inquiry not advocacy) for successful agile problem-solving

- Execute chosen actions but treat them as tentative and experimental

- Set reasonable expectations that you are making your best effort, learning rapidly, not everything will work, and we’ll keep working until it does

Hmmmmm, sounds exactly like how innovation works, too.

We’re all in The Big Squiggly Together

Everyone is innovating right now. From big companies responding to the Great Resignation and supply chain disruptions, to individuals trying to figure out whether and when to work form home or the office . We’re all doing something different, hoping it creates value, and pivoting until it does.

Yes, we are being forced to innovate and, like all innovation efforts, we’re not getting everything perfect but we’re learning a heck of a lot. Just imagine what we could do if we keep innovating when the crisis ends. Imagine the problems we could solve and the things we could create if we choose to continue to listen, learn, and experiment!

My friend, Dr. Anne Waple, has been a climate scientist for over 25 years. About a year ago, she spoke at Speakers Who Dare about her vision for Earth’s Next Chapter. Even in the early days of America’s response to COVID-19, Anne encouraged people to not just focus on problems because, when we do that, we don’t actually solve them. Instead, she asserted, driving positive, big, lasting global change starts when we ask questions about the world we want and believe we can have fun making it happen.

Together, We Can Get Out of The Big Squiggly

We are not lost. We’re just not where we want to be right now.

Yes, The Big Squiggly is uncomfortable and stressful. But it’s not forever. By asking questions about the world we want, we can define “over there somewhere.” How we get there is through innovation and we know and are already practicing the steps.

by Robyn Bolton | Oct 7, 2021 | Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

“Innovation happens in the gaps.”

It’s a statement so simple yet so profound that as soon as my client said it, I wrote it down.*

It’s not sexy to innovate in the gaps.

Most people and companies believe that innovation must be something entirely new for the world. That innovation is all about filling a white space, thinking blue sky, or swimming in a blue ocean. That innovation must be free of constraints, that it must be pure creation.

Most people will argue that CEOs rarely get on the front page of the Wall Street Journal because their company introduced something better than what exists today. Innovators rarely win design awards for an improved version of an existing solution. Scientists and engineers are rarely celebrated for receiving improvement patents.

Rarely.

Steve Jobs made the front page for the iPod, an MP3 player that offered better storage and user experience than the dozens of MP3 players that existed before it.

Charles and Ray Eames were named “The Most Influential Designer of the 20th Century” by the Industrial Designers Society of America, and they’re best known for designing chairs.

Thomas Edison is hailed as the inventor of the electric lightbulb when, in truth, he significantly improved a decades-old product that was too expensive, too unreliable, and too short-lived to be commercially viable.

It’s necessary (and profitable) to innovate in the gaps.

Gaps exist because of real and perceived constraints. Innovation thrives in constraints because it is the constraints that drive creativity.

In the gap between what is and what is good enough lies a problem that needs a solution. That solution, something new that creates value, is innovation.

In the gap between what is and what is delightful lies an opportunity that wants a better solution. Innovation can deliver that solution.

Find the gaps

Sometimes gaps are obvious, like the cost and performance gap between candles and early light bulbs that contained costly platinum and only lasted a few hours.

Sometimes they’re not, as evidenced by the difference between people who owned MP3 players before the iPod versus after the iPod debuted.

To find the gaps, talk to customers. What do they use now and why? What do they not use and why? What do they wish for and why? What is not good enough and why? What is delightful and why?

To find the gaps, don’t sit in a conference room. You won’t learn anything new by talking to the same people. And don’t obsess about competition. If you do what competitors are doing, you’ll do no better than your competitors.

Talk to your customers. They’ll point out the gaps. Then innovate to fill them.

*I learned later that he had first heard it from Tim Kastelle, an Australian academic and author focused on innovation.

by Robyn Bolton | Sep 6, 2021 | Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

We are natural problem-solvers.

From the moment we’re born, we’re solving problems.

Hungry? We wail and cry

Confused at school? We raise our hands.

Computer not working properly? We unplug it and plug it back in.

From the moment we enter the workplace, we’re solving problems.

Boss doesn’t want to hear problems? We bring solutions.

Customers upset about something? We offer compensation.

Unhappy at work? We find other jobs.

We focus on solutions because it gives us a sense of confidence and control. In a constantly changing world and where we, in fact, have very little control, solving a problem gives us a momentary reprieve. It gives us something we can point to and say, “that is better because of me.”

We don’t focus on problems because it is uncomfortable, and it can feel like a failure. Spending time with a problem means we haven’t solved it and may give others the impression we can’t solve it.

But what if we’re solving the wrong problems?

What if the boss is overwhelmed and burned out and feels unable to take on one more thing? How will one more solution to one more problem fix that?

What if the customer is upset because they relied on your company’s promise, and now a significant event is ruined because you didn’t deliver? What compensation will make up for that?

What if you’re unhappy to work because your passion and abilities are in a completely different profession? How will a new job fix that?

We can’t be confident that we’re solving the real problem if we don’t spend time with a problem, ask questions, and dig until we get past the symptoms and find the root cause.

Innovation is all about solving problems. The REAL problems.

This is why true innovators start by seeking problems. They spend weeks if not months asking questions, examining things from multiple angles, building empathy, and never ever ever settling for the first answer offered.

Innovators know that to succeed, they need to fall in love with a problem, not their solution. And in innovation, just like in life, you need to spend time with something to fall in love with it. You need to learn about it, understand it, connect with it, and care about it. Just as you wouldn’t walk up to a complete stranger and propose marriage, you shouldn’t walk up to a problem and propose a solution.

How to find the REAL problems.

- Set aside your ego. Innovation isn’t about you, your business, what you want or need to accomplish. Your customers don’t care about your problems. They care about their problems.

- Create time for the problem. As much as we’re tempted to rush to solutions, we’re also pushed to them by our bosses and the pace of business. But solving the wrong problem puts you even further behind, so set aside 4-6 weeks to ask questions, learn, and find the real problem.

- Celebrate not knowing. It’s ok if you find a problem that you don’t know how to solve. In fact, it’s great! Because if you don’t know how to solve it, odds are your competitors don’t know either. And that means you have a head start on solving a very important problem – the one your customers care about the most.

Being a “natural” isn’t the same as being the best.

We are natural problem solvers, but if we’re not solving the real problems, we’re not the best problem solvers we can be. And that is a problem that You can solve.