by Robyn Bolton | Mar 4, 2025 | Automation & Tech, Leadership

Imagine a manufacturing company. On the factory floor, machines whirl and grind, torches flare up as welding helmets click closed, and parts and products fall off the line and into waiting hands or boxes, ready to be shipped to customers. Elsewhere, through several doors and a long hallway, you leave the cacophony of the shop floor for the quiet hum of the office. Computers ping with new emails while fingers clickety-clack across the keyboard. Occasionally, a printer whirs to life while forcing someone to raise their voice as they talk to a customer on the other end of the phone.

Now, imagine that you ask each person whether AI and automation will positively or negatively affect their jobs. Who will champion new technology and who will resist it?

Most people expect automation acceptance to be separated by the long hallway, with the office workers welcoming while the factory workers resist.

Most people are wrong.

The Business Case for Problem-Solving Job Design

Last week, I wrote about findings from an MIT study that indicated that trust, not technology, is the leading indicator of whether workers will adopt new AI and automation tools.

But there’s more to the story than that. Researchers found that the type of work people do has a bigger influence on automation perception than where they do it. Specifically, people who engage in work requiring high levels of complex problem-solving alongside routine work are more likely to see the benefit of automation than any other group.

Or, to put it more simply

While it’s not surprising that people who perform mostly routine tasks are more resistant than those who engage in complex tasks, it is surprising that this holds true for both office-based and production-floor employees.

Even more notable, this positive perception is significantly higher for complex problem solvers vs. the average across all workers::

- Safety: 43% and 41% net positive for office and physical workers, respectively (vs. 32% avg)

- Pay: 27% and 25% net positive for physical and office workers, respectively (vs. 3.9% avg)

- Autonomy: 33% net positive for office workers (vs. 18% average)

- Job security: 25% and 22% net positive for office and physical workers, respectively (vs. 3.5%)

Or, to put it more simply, blend problem-solving into routine-heavy roles, and you’ll transform potential technology resistors into champions.

3 Ways to Build Problem-Solving Into Any Role

The importance of incorporating problem-solving into every job isn’t just a theory – it’s one of the core principles of the Toyota Production System (TPS). Jidoka, or the union of automation with human intelligence, is best exemplified by the andon cord system, where employees can stop manufacturing if they perceive a quality issue.

But you don’t need to be a Six-Sigma black belt to build human intelligence into each role:

- Create troubleshooting teams with decision authority

Workers who actively diagnose and fix process issues develop a nuanced understanding of where technology helps versus hinders. Cross-functional troubleshooting creates the perfect conditions for technology champions to emerge.

- Design financial incentives around problem resolution

The MIT study’s embedded experiment showed that financial incentives significantly improved workers’ perception of new technologies while opportunities for input alone did not. When workers see personal benefit in solving problems with technology, adoption accelerates.

- Establish learning pathways connected to problem complexity

Workers motivated by career growth (+33.9% positive view on automation’s impact on upward mobility) actively seek out technologies that help them tackle increasingly complex problems. Create visible advancement paths tied to problem-solving mastery.

Innovation’s Human Catalyst

The most powerful lever for technology adoption isn’t better technology—it’s better job design. By restructuring roles to include meaningful problem-solving, you transform the innovation equation.

So here’s the million-dollar question every executive should be asking: Are you designing jobs that create automation champions, or are you merely automating jobs as they currently exist?

by Robyn Bolton | Feb 26, 2025 | Automation & Tech, Innovation

We’ve all seen the apocalyptic headlines about robots coming for our jobs. The AI revolution has companies throwing money at shiny new tech while workers polish their résumés, bracing for the inevitable pink slip. But what if we have it completely, totally, and utterly backward? What if the real drivers of automation success have nothing to do with the technology itself?

That’s precisely what an MIT study of 9,000+ workers across nine countries asserts. While the doomsayers have predicted the end of human workers since the introduction of the assembly line, those very workers are challenging everything we think we know about automation in the workplace.

The Secret Ingredient for Technology ROI

MIT surveyed workers across the manufacturing industry—50% of whom reported frequently performing routine tasks—and found that the majority ultimately welcome automation. But only when one critical condition is present. And it’s one that most executives completely miss while they’re busy signing purchase orders for the latest AI and automation systems.

Trust.

Read that again because while you’re focused on selecting the perfect technology, your actual return depends more on whether your team feels valued and believes you are invested in their safety and professional growth.

Workers Who Trust, Automate

This trust dynamic explains why identical technologies succeed in some organizations and fail in others. According to MIT’s research:

- Job satisfaction is the second strongest indicator of technology acceptance, with a 10% improvement that researchers identified as consistently significant across all analytical models

- Feeling valued by their employer shows a highly significant 9% increase in positive attitudes toward automation

- Trust also consistently predicts automation acceptance, as workers scoring higher on trust measures are significantly more likely to view new technologies positively.

For example, Sam Sayer, an employee at a New Hampshire cutting tool manufacturer, has become an automation champion because his employer helped him experience how factory-floor robots could free him from routine tasks and allow him to focus on more complex problem-solving. “I worked in factories for years before I ever saw a robot. Now I’m teaching my colleagues on the factory floor how to use them.”

This contrasts with an aerospace manufacturer in Ohio that hired a third party to integrate a robot into its warehouse processes. Despite the company’s efforts to position the robot as a teammate, even giving it a name, workers resisted the technology because they didn’t trust the implementation process or see clear personal benefits.

These patterns hold across industries and countries: When workers perceive their employer as invested in their development and well-being, automation initiatives succeed. When that foundation is missing, even the most sophisticated technologies falter.

Four Steps to Convert Resistors to Champions

Whether it’s for the factory floor or the office laptop, if you want ROI and revenue growth from your automation investments, start with your people:

- Design roles that connect workers to outcomes: When people see how their input shapes results, they become natural technology allies.

- Create visible growth pathways. Workers motivated by career advancement are significantly more likely to embrace new technologies.

- Align financial incentives with implementation goals. When workers see the personal benefits of adoption, resistance evaporates faster than free donuts in the break room.

- Make safety improvements the leading edge of your technology story. It’s the most universally appreciated benefit of automation.

A Provocative Challenge

Ask yourself this (potentially) uncomfortable question: Are you investing as much in trust as you are in technology?

Because if not, you might as well set fire to a portion of your automation budget right now. At least you’d get some heat from it.

The choice isn’t between technology and workers—it’s between implementations that honor human relationships and those that don’t. The former generates returns; the latter generates résumé updates.

What are you choosing?

by Robyn Bolton | Feb 12, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership

When times get tough, the first things most companies cut are the “luxuries.” That includes their innovation teams. But as companies dismantle their labs, teams, and other structures, a crucial question emerges: Who’s working on growth?

Cutting innovation teams doesn’t just cut a branch off the org chart. It eliminates capabilities that are fundamental to sustaining and growing a business and culture.

So why throw the baby out with the bathwater? Here’s a scenario that might sound familiar: Your innovation team created something brilliant. The prototype works, early users love it, and the business case is solid. But six months later, it’s gathering dust because no one in the core business knew how to—or wanted to—move it forward.

This isn’t a failure of innovation. It’s a failure of integration.

Wait, I thought integrating innovation with the core business was bad

The traditional innovation team structure – a separate unit with its own space, processes, and culture – solved one problem but created another.

As innovation teams were given the freedom to think differently, they were also given shiny, new, fun, and amenity-filled spaces cordoned off from everyone else. Meanwhile, “everyone else” was stuck in their usual offices and doing the usual things that keep the business running and fund the innovation team’s luxe life.

The resulting us-versus-them mentality fueled resentment, making it easy for “everyone else” to stonewall the innovation team’s efforts by pointing out flaws, uncertainties, and risks.

To be fair, they weren’t doing this to be mean – they were protecting the business. The innovators, meanwhile, grew frustrated, sought help from higher-ups who were happy to help until times got tough and cuts had to be made.

So, one team should work on both innovation and the core business?

Just like we need multiple words to describe the what and why of innovation, we need different operating models that embed innovation capabilities across the organization while protecting the space for them to flourish.

Here’s what it looks like:

- For Core Improvements, let your operational teams lead. They know the problems best, but give them innovation tools and methods. Think of this as equipping your existing workforce with new superpowers, not replacing them with superheroes.

- For Adjacent Expansions, create hybrid teams that combine operational experience with innovation expertise. When expanding into new markets or launching new products, you need both an innovative mindset and operational know-how. Neither alone is sufficient.

- For Radical Reinvention, you still need dedicated teams—but not isolated ones. Their job is to create offerings that reinvent the company and the culture that enables everyone to participate. Establish bridges that connect them with business units and enforce quarterly meetings to share progress, insights, and tools.

This isn’t theory.

Companies like Amazon have been doing this for years with their “working backwards” innovation process used by all teams, not just a special innovation unit. When I worked at P&G, the brand teams worked on core improvements, the New Business Development teams (where I worked) physically sat next to the brand teams and worked on Adjacent expansion, and the radical reinvention teams were co-located with R&D at the technical centers.

Put it into practice

Here’s where to start:

- Map your innovation portfolio to understand what types of innovation you need to hit your goals

- Match your team structures to your innovation types

- Start embedding innovation capabilities across the organization

- Create clear paths for innovations to move from idea to implementation

The transition isn’t easy. It requires rethinking roles and reimagining how innovation happens in your organization. But the alternative – watching your innovation investments evaporate because they can’t cross the bridge back to the core business – is far more painful.

What’s your experience? Drop your stories and strategies in the comments. Let’s figure this out together.

by Robyn Bolton | Feb 3, 2025 | Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

If innovation (the term) is dead and we will continue to engage in innovation (the activity), how do we talk about creating meaningful change without falling back on meaningless buzzwords? The answer isn’t finding a single replacement word – it’s building a new innovation language that actually describes what we’re trying to achieve. Think of it as upgrading from a crayon to a full set of oil paints – suddenly you can create much more nuanced pictures of progress.

The Problem with One-Size-Fits-All

We’ve spent decades trying to cram every type of progress, change, and improvement into the word “innovation.” It’s like trying to describe all forms of movement with just the word “moving.” Sure, you’re moving but without the specificity of words like walking, running, jumping, bounding, and dancing, you don’t know what or how you’re moving or why.

That’s why using “innovation” to describe everything different from today doesn’t work.

Use More Precise Language for What and How

Before we throw everything out, let’s keep what actually works: Innovation means “something new that creates value.” That last bit is crucial – it’s what separates meaningful change from just doing new stuff for novelty’s sake. (Looking at you, QR code on toothpaste tutorials.)

But, just like “dancing” is a specific form of movement, we need more precise language to describe what the new value-creating thing is that we’re doing:

- Core IMPROVEMENTS: Making existing things better. It’s the unglamorous but essential work of continuous refinement. Think better batteries, faster processors, smoother processes.

- Adjacent EXPANSIONS: Venturing into new territory – new customers, new offerings, new revenue models, OR new processes. It’s like a restaurant adding delivery service: same food, new way of reaching customers.

- Radical REINVENTION: Going all in, changing multiple dimensions at once. Think Netflix killing its own DVD business to stream content they now produce themselves. (And yes, that sound you hear is Blockbuster crying in the corner.)

Adopt More Sophisticated Words to Describe Why

Innovation collapsed because innovation became an end in and of itself. Companies invested in it to get good PR, check a shareholder box, or entertain employees with events.

We forgot that innovation is a means to an end and, as a result, got lazy about specifying what the expected end is. We need to get back to setting these expectations with words that are both clear and inspiring

- Growth means ongoing evolution

- Transformation means fundamental system change (not just putting QR codes on things)

- Invention means creating something new without regard to its immediate usefulness

- Problem Solving means finding, creating, and implementing practical solutions

- Value Creation means demonstrating measurable and meaningful impact

Why This Matters

This isn’t just semantic nitpicking. Using more precise language sets better expectations, helps people choose the most appropriate tools, and enables you to measure success accurately. It’s the difference between saying “I want to move more during the day” and “I want to build enough endurance to run a 5K by June.”

What’s Next?

As we emerge from innovation’s chrysalis, maybe what we’re becoming isn’t simpler – it’s more sophisticated. And maybe that’s exactly what we need to move forward.

Drop a comment: What words do you use to describe different types of change and innovation in your organization? How do you differentiate between what you’re doing and why you’re doing it?

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 15, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Stories & Examples

I firmly believe that there are certain things in life that you automatically say Yes to. You do not ask questions or pause to consider context. You simply say Yes:

- Painkillers after a medical procedure

- Warm blankets

- The opportunity to listen to brilliant people talk about things that fascinate them.

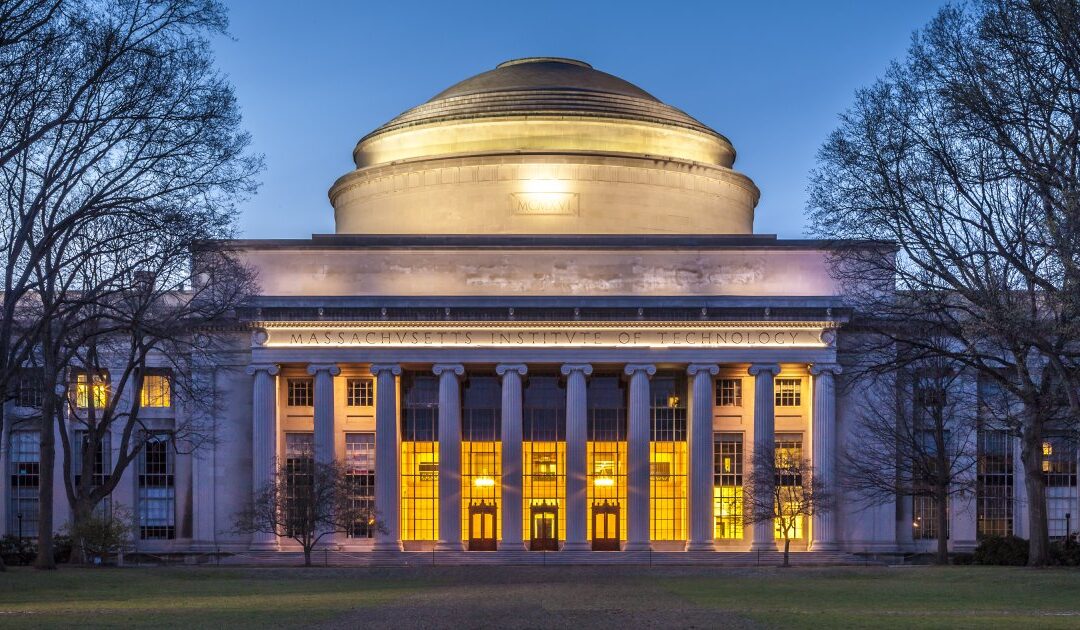

So, when asked if I would like to attend an Executive Briefing curated by MIT’s Industrial Liaison Program, I did not ask questions or pause to check my calendar. I simply said Yes.

I’m extremely happy that I did because what I heard blew my mind.

Lean is the enemy of learning

When Ben Armstrong, Executive Director of MIT’s Industrial Performance Center and Co-Lead of the Work of the Future Initiative, said, “To produce something new, you need to create a lot of waste,” I nearly lept out of my chair, raised my arms, and shouted “Amen brother!”

He went on to tell the story of a meeting between Elon Musk and Toyota executives shortly after Musk became CEO. Toyota executives marveled at how quickly Tesla could build an EV and asked Musk for his secret. Musk gestured around the factory floor at all the abandoned hunks of metal and partially built cars and explained that, unlike Toyota, which prided itself on being lean and minimizing waste, Tesla engineers focused on learning – and waste is a required part of the process.

We decide with our hearts and justify with our heads – even when leasing office space

John E. Fernández, Director of MIT’s Environmental Solutions Initiative, shared an unexpected insight about selling sustainable buildings effectively. Instead of hard numbers around water and energy cost savings, what convinces companies to pay the premium for Net Zero environments is prestige. The bragging rights of being a tenant in Winthrop Center, Boston’s first-ever Passive House office building, gave developers a meaningful point of differentiation and justified higher-than-market-rate rents to future tenants like McKinsey and M&T Bank.

49% of companies are Silos and Spaghetti

I did a hard eye roll when I saw Digital Transformation on the agenda. But Stephanie Woerner, Principal Research Scientists and Executive Director for MIT’s Center for Information Systems Research, proved me wrong by explaining that Digital Transformation requires operational excellence and customer-focused innovation.

Her research reveals that while 26% of companies have evolved to manage both innovation and operations, operate with agility, and deliver great customer experiences, nearly half of companies are stuck operating in silos and throwing spaghetti against the wall. These “silo and spaghetti companies” are often product companies rife with complex systems and processes that require and reward individual heroics to make progress.

What seems like the safest option is the riskiest

How did 26% of companies transform while the rest stayed stuck or made little progress? The path forward isn’t what you’d expect. Companies that go all-in on operational excellence or customer innovation struggle to shift focus and work in the other half of the equation. But doing a little bit of each is even more risky because the companies often wait for results from one step before taking the next. The result is a never-ending transformation slog that is eventually abandoned.

Academia is full of random factoids

They’re not random to the academics, but for us civilians, they’re mainly helpful for trivia night:

- 50% of US robots are used in the automotive industry

- <20% of manufacturing job descriptions require digital skills (yes, that includes MS Office)

- Data centers will account for 8-21% of global energy demand by 2030

- Energy is 10% of the cost of running a data center but 90% of the cost of mining bitcoin

- Cities take up 3% of the earth’s surface, contain 33% of the population, account for 70% of global electricity consumption, and are responsible for 75% of CO2 emissions

Why say Yes

When brilliant people talk about things they find fascinating, it’s often because those things challenge conventional wisdom. The tension between lean efficiency and innovative learning, the role of emotion in business decisions, and the risks of playing it too safe all point to a fascinating truth: sometimes the most counterintuitive path forward is the most successful.

How have you seen this play out in your work?