by Robyn Bolton | Oct 17, 2024 | Podcasts

by Robyn Bolton | Oct 14, 2024 | Innovation, Leadership, Stories & Examples

Once upon a time, in a lush forest, there lived a colony of industrious beavers known far and wide for their magnificent dams, which provided shelter and sustenance for many.

One day, the wise old owl who governed the forest decreed that all dams must be rebuilt to withstand the increasingly fierce storms that plagued their land. She gave the beavers two seasons to complete it, or they would lose half their territory to the otters.

The Grand Design: Blueprints and Blind Spots

The beaver chief, a kind fellow named Oakchew, called the colony together, inviting both the elder beavers, known for their experience and sage advice and the young beavers who would do the actual building.

Months passed as the elders debated how to build the new dams. They argued about mud quantities, branch angles, and even which mix of grass and leaves would provide structural benefit and aesthetic beauty. The young beavers sat silently, too intimidated by their elders’ status to speak up.

Work Begins: Dams and Discord

As autumn leaves began to fall, Oakchew realized they had yet to start building. Panicked, he ordered work to commence immediately.

The young beavers set to work but found the new method confusing and impractical. As time passed, progress slowed, panic set in, arguments broke out, and the once-harmonious colony fractured.

One group insisted on precisely following the new process even as it became obvious that they would not meet the deadline. Another reverted to their old ways, believing that a substandard something was better than nothing. And one small group went rogue, retreating to the smallest stream to figure it out for themselves.

As the deadline grew closer, the beavers worked day and night, but progress was slow and flawed. In desperation, Oakchew called upon the squirrels to help, promising half the colony’s winter food stores.

Just as the first storm clouds gathered, Oakchew surveyed the completed dams. Many were built as instructed, but the rushed work was evident and showed signs of weakness. Most dams were built with the strength and craftsmanship of old but were likely to fail as the storms’ intensity increased. One stood alone and firm, roughly constructed with a mix of old and new methods.

Wisdom from the Waters: Experiments and Openness

Oakchew’s heart sank as he realized the true cost of their efforts. The beavers had met their deadline but at a great cost. Many were exhausted and resentful, some had left the colony altogether, and their once-proud craftsmanship was now shoddy and unreliable.

He called a final meeting to reflect on what had happened. Before the elders could speak, Oakchew asked the young beavers for their thoughts. The colony listened in silent awe as the young builders explained the flaws in the “perfect” process. The rogue group explained that they had started building immediately, learning from each failure, and continuously improving their design.

“We wasted so much time trying to plan the perfect dam,” Oakchew admitted to the colony. “If we had started building sooner and learned from our mistakes, we would not have paid such a high cost for success. We would not have suffered and lost so much if we had worked to ensure every beaver was heard, not just invited.”

From that day forward, the beaver colony adopted a new approach of experimentation, prototyping, and creating space for all voices to be heard and valued. While it took many more seasons of working together to improve their dams, replenish their food stores, and rebuild their common bonds, the colony eventually flourished once more.

The Moral of the Story (just in case it isn’t obvious)

The path to success is paved not with perfect plans but with the courage to act, the wisdom to learn from failures, and the openness to embrace diverse ideas. True innovation arises when we combine the best of tradition with the boldness of experimentation.

by Robyn Bolton | Oct 9, 2024 | Innovation, Leadership

In our race to enable and support hybrid teams, our reliance on collaboration software has inadvertently caused us to forget the art of true collaboration.

The pandemic forced us to rely on digital platforms for communication and creativity. But as we embraced these tools, something essential was lost in translation. Last week, I watched team members sitting elbow-to-elbow spend two hours synthesizing discovery interviews and debating opportunity areas entirely by chat.

What collaboration is

“Collaboration” seems to have joined the ranks of meaningless corporate buzzwords. In an analysis of 1001 values from 172 businesses, “collaboration” was the #2 most common value (integrity was #1), appearing in 23% of the companies’ value statements.

What it means in those companies’ statements is anyone’s guess (we’ve all been in situations where stated values and lived values are two different things). But according to the dictionary, collaboration is “the situation of two or more people working together to create or achieve the same thing.”

That’s a short definition with a lot of depth.

- “The same thing” means that the people working together are working towards a shared goal in which they have a stake in the outcome (not just the completion).

- “Working together” points towards interdependence, that everyone brings something unique to the work and that shared goal cannot be achieved without each person’s unique contribution.

- “Two or more people” needing each other to achieve a shared outcome requires a shared sense of respect, deep trust, and vulnerability.

It’s easy to forget what “collaboration” means. But we seem to have forgotten how to do it.

What collaboration is not

As people grow more comfortable “collaborating” online, it seems that fewer people are actually collaborating.

Instead, they’re:

- Transacting: There is nothing wrong with email, texts, or messaging someone on your platform of choice. But for the love of goodness, don’t tell me our exchange was a collaboration. If it were, every trip to the ATM would be a team-building exercise.

- Offering choices: When you go out to eat at a fast-food restaurant, do you collaborate with the employee to design your meal? No. You order off a menu. Offering a choice between two or three options (without the opportunity to edit or customize the options), isn’t collaboration. It’s taking an order.

- Complying: Compliance is “the act of obeying a law or rule, especially one that controls a particular industry or type of work.” Following rules isn’t collaboration, it’s following a recipe

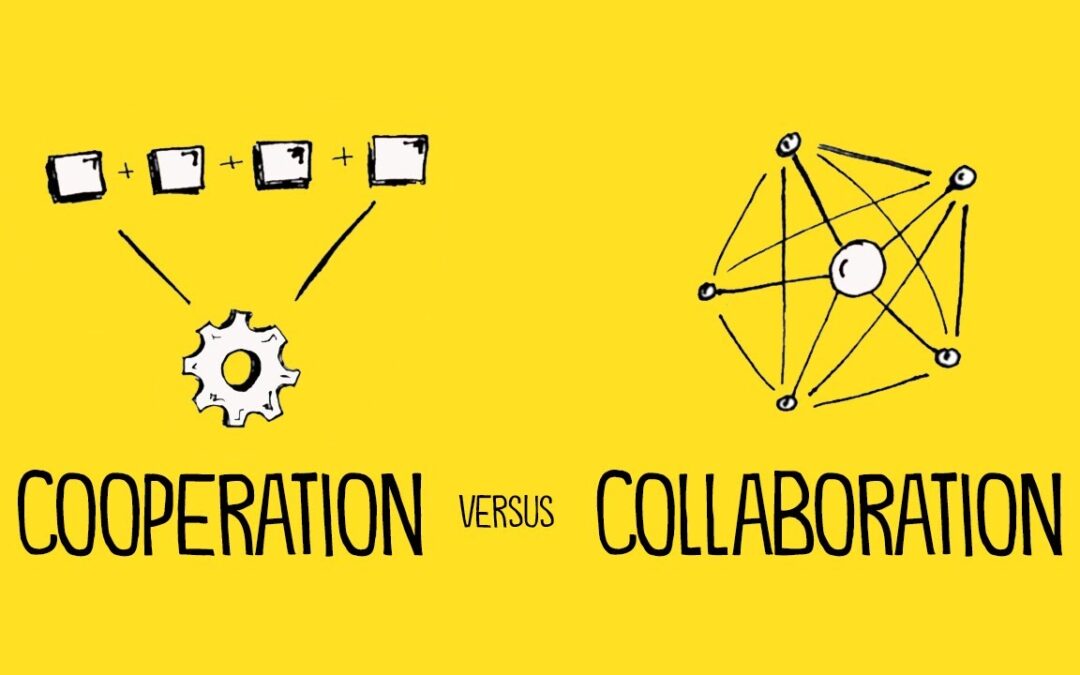

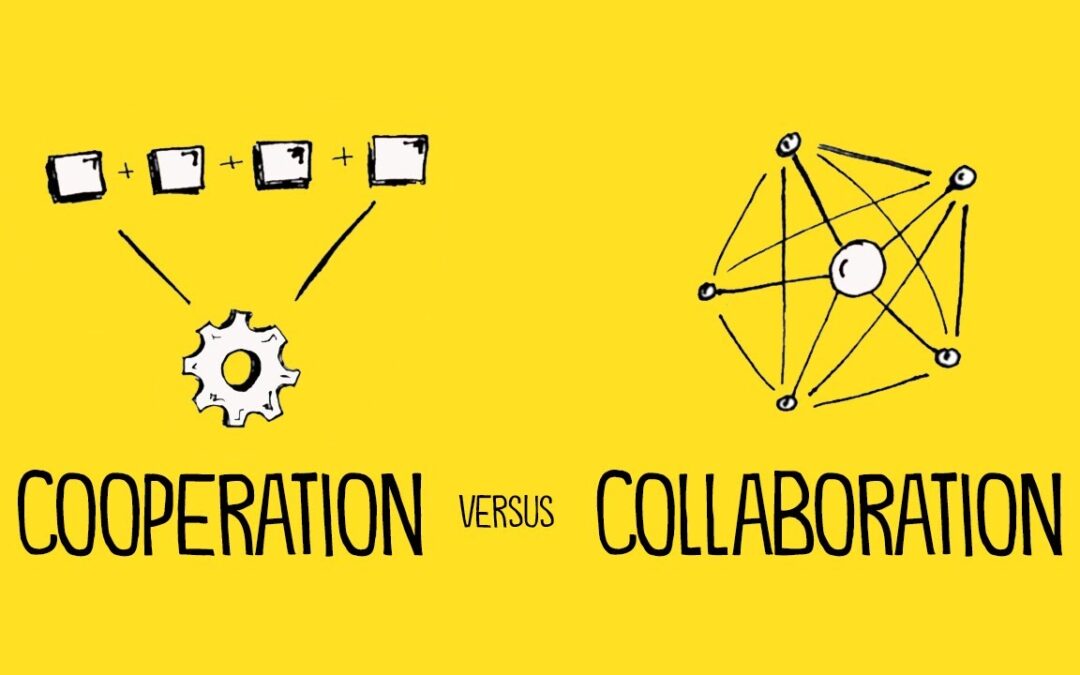

- Cooperating: Cooperation is when two or more people work together independently or interdependently to achieve someone else’s goal. Collaboration requires shared objectives and ownership, not just shared tasks and timelines.

There’s nothing wrong with any of these activities. Just don’t confuse them with collaboration because it sends the wrong message to your people.

Why this matters

This isn’t an ivory-tower debate about semantics.

When people believe that simple Q&A, giving limited and unalterable options, following rules, and delivering requests are collaboration, they stop thinking. Curiosity, creativity, and problem-solving give way to efficiency and box-checking. Organizations stop exploring, developing, and innovating and start doing the same thing better, faster, and cheaper.

So, if you truly want your organization to grow because it’s filled with creative and empathetic problem-solvers, invest in reclaiming the true spirit of collaboration. After all, the next big idea isn’t hiding in a chat log—it’s waiting to be born in the spark of genuine collaboration.

by Robyn Bolton | Sep 18, 2024 | Podcasts

by Robyn Bolton | Sep 17, 2024 | Leadership, Stories & Examples, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

How many times have you proposed a new idea and been told, “We can’t do that?” Probably quite a few. My favorite memory of being told, “We can’t do that,” happened many years ago while working with a client in the publishing industry:

Client: We can’t do that.

Me: Why?

Client: Because we already tried it, and it didn’t work.

Me: When did you try it?

Client: 1972

Me: Well, things certainly haven’t changed since 1972, so you’re right, we definitely shouldn’t try again.

I can only assume they appreciated my sarcasm as much as the idea because we eventually did try the idea, and, 30+ years later, it did work. But the client never would have enjoyed that success if my team and I had not seen through “we can’t do that” and helped them admit (confess) what they really meant.

Quick acknowledgment

Yes, sometimes “We can’t do that” is true. Laws and regulations define what can and can’t be done. But they are rarely as binary as people make them out to be. In those gray areas, the lie of “we can’t do that” obscures the truth of won’t, not able to, and don’t care.

“I won’t do it.”

When you hear “can’t,” it usually means “won’t.” Sometimes, the “won’t” is for a good reason – “I won’t do the dishes tonight because I have an urgent deadline, and if I don’t deliver, my job is at risk.” Sometimes, the “won’t” isn’t for a good reason – “I won’t do the dishes because I don’t want to.” When that’s the case, “won’t” becomes “can’t” in the hope that the person making the request backs off and finds another solution.

For my client, “We can’t do that” actually meant, “I won’t do that because it failed before and, even though that was thirty years ago, I’m afraid it will fail again, and I will be embarrassed, and it may impact my reputation and job security.”

You can’t work with “can’t.” You can work with “won’t.” When someone “won’t” do something, it’s because there’s a barrier, real or perceived. By understanding the barrier, you can work together to understand, remove, or find a way around it.

“I’m not able to do it.”

“Can’t” may also come with unspoken caveats. We can’t do that because we’ve never done it before and are scared. We can’t do that because it is outside the scope of our work. We can’t do that because we don’t know how.

Like “won’t,” you can work with “not able to” to understand the gap between where you are now and where you want to go. If it’s because you’re scared of doing something new, you can have conversations to get smarter about the topic or run small experiments to get real-world learnings. If you’re not able to do something because it’s not within your scope of work, you can expand your scope or work with people who have it in their scope. If you don’t know how, you can talk to people, take classes, and watch videos to learn how.

“I don’t care.”

As brave as it is devastating, “we can’t do that” can mean “I don’t care enough to do that.”

Executives rarely admit to not caring, but you see it in their actions. When they say that innovation and growth are important but don’t fund them or pull resources at the first sign of a wobble in the business, they don’t care. If they did care, they would try to find a way to keep investing and supporting the things they say are priorities.

Exploring options, trying, making an effort—that’s the difference between “I won’t do it” and “I don’t care.” “I won’t do that” is overcome through logic and action because the executive is intellectually and practically open to options. “I don’t care” requires someone to change their priorities, beliefs, and self-perception, changes that require major personal, societal, or economic events.

Now it’s your turn to tell the truth

Are you willing to ask the questions to find them?