The Disruption Dilemma

It’s been 22 years since the publication of The Innovator’s Dilemma, the book that catapulted Clayton Christensen to guru status, shocked and scared executives at large companies, and brought innovation into the mainstream.

In the decades since, “innovation,” “disruption,” and a host of related terms have become meaningless buzzwords, a massive industry of consultants and advisors (yes, including Mile Zero) has sprung up, and an untold number of books and articles have been written about how to innovate.

Yet nothing has changed.

Large organizations still struggle to launch anything other than incremental innovations, the failure rate of start-ups remains astoundingly high, and executives continue to flock to the latest innovation trend (2019 seems to be the year of Corporate Venture Capital).

Why?

That’s the question that Joshua Gans, Professor of Strategic Management and holder of the Jeffrey S. Skoll Chair of Technical Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, tries to answer in his book The Disruption Dilemma.

He starts by grounding the reader in the core definitions and theories related to disruption, then makes the case that rather than trying to predict disruption (a difficult if not impossible task) organization should instead follow one of four strategies, before wrapping up with a re-examination of the data and research Christensen used to create his original theory of disruption.

“Disruption” is more than a new technology…it is an identity crisis

in their 1995 Harvard Business Review article, “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave,” Clayton Christensen and Joseph L. Bower coined the term “disruptive technology” and defined it as having

“two important characteristics: First they present a different package of performance attributes — one that, at least at the outset are not valued by existing customers. Second, the performance attributes that existing customers do value improve at such a rapid rate that the new technology can later invade those established markets.”

For Christensen. disruption occurs when management chooses not respond to a new innovation because it does not perform as well as existing solutions along traditional performance dimensions and therefore is unappealing to existing customer.

Interestingly, at the same time that Christensen was studying for his PhD at Harvard, another doctoral student was also conducting research into why successful firms fail in light of new technologies. In 1990, Rebecca Henderson, now one of only two University Professors at Harvard (the other one is Michael Porter), debuted the term “Architectural Innovation” with her collaborator, Kim Clark, in their paper “Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and The Failure of Established Firms.”

For Henderson, disruption, happens when managers are unable to respond because the innovation requires changes to how the firm operates, communicates, coordinates, learns, and makes decisions. Thus,

“Architectural innovation presents established firms with a more subtle challenge. Much of what the firm knows is useful and needs to be applied in the new product but some of what it knows is not only not useful but may actually handicap the firm. Recognizing what is useful and what is not, and acquiring and applying new knowledge when necessary, may be quite difficult for an established firm….”

Gans terms the Christensen theory demand-side disruption and the Henderson theory supply-side disruption. He unites both of these two types of disruption under a single definition of disruption as

“what a firm faces when the choices that once drive a firm’s success now become those that destroy its future.”

What I like about this definition is that it takes disruption beyond the narrow fields of technology, products, or services and considers it in the broader context of markets and industries. It reveals disruption to be something that all organizations are likely to face at some point in their future and one that will call into question many of the fundamental beliefs upon which the organization operates. Further, identifying and understanding both demand- and supply-side disruption can help organizations understand the challenge they face and where and how to focus their resources to navigate the rough road ahead.

Kodak Smile and the Polaroid Mint

Predicting disruption is hard.

What both demand-side Disruption (Christensen) and supply-side Disruption (Henderson) theories have in common is that they are kicked off by the introduction of a new innovation into the market.

However, new innovations launch all the time and very few of them start the domino effect that characterizes disruption. This is because an innovation must do two things in order to be disruptive: (1) offer poorer performance on some dimensions that existing customers value and offer new performance benefits that appeal to new customers and (2) improve rapidly enough that the innovation is able to quickly perform at levels desired by existing customers while offering the new benefits that new customers have grown to love.

As Gans point out, it’s relatively easy to determine if an innovation will meet the first criteria but it takes time to know whether or not the second criteria will be met. “Therefore, both supply- and demand-side theories lead to the conclusion that predicting disruptive events is very challenging, if not impossible.”

Responding is even harder.

To illustrate this point, Gans shares the stories of Polaroid and Kodak, two companies that recognized and responded to a potentially disruptive innovation decades before it transformed the market, but still failed.

In 1981, Polaroid recognized the threat posed by digital technologies. By 1989, it was investing over 40% of its R&D budget into digital imaging. However, while it was investing in technology, it was struggling to envision the right products to commercialize its technological advancement. This struggle was rooted not in its ability to innovate cameras but rather by “razor/blade” business model (and supporting mindset) that resulted in Polaroid subsidizing cameras and making money on film, a model (architecture) that would need to change if the company shifted from film to digital technology.

The company resisted re-organizing itself around the new architecture such that when it eventually developed and launched a digital camera it into the market, there were already 40 established competitors and Polaroid struggled to differentiate itself. Five years later, in 2001, Polaroid declared bankruptcy.

Digital imaging technology had been on Kodak’s radar screen since the mid-1970s. In the 1990s, it partnered with companies like Apple to develop digital cameras and, by 2005, was the market leader in docks that enabled sharing of digital images between computers and cameras.

So prescient were Kodak’s senior executives that “it was even one of the first few companies to consult with Clayton Christensen himself. Managers at Kodak read the Innovator’s Dilemma upon its publication and used it messages to direct Kodak’s product strategy. One example of this was to launch cameras in toy stores as a defense against Nintendo, which had put them in one million Game Boys. Nintendo’s cameras were by all accounts awful, but they were enough to get Kodak worried about disruption. Kodak was able to outpredict the market and to make substantial investments in what came to be disruptive innovations. Though they were initially inferior on multiple dimensions, the improved to take the market in less than a decade.”

If Kodak did everything right, at least according to Christensen’s theory, why did it declare bankruptcy in 2012?

It failed because it did not predict that the dominant design for digital photos would shift from cameras to phones and continued to innovate and invest in “hybrid products that would combine its existing strengths with the new technologies, for example the Photo CD, a way of taking film to photo shops and bringing a digital product home.”

The moral or these stories is that if you are able to identify a potentially disruptive innovation and if you take action to respond, it is nearly impossible to predict the path the innovation will take and attempting to do so is likely to require considerable resources but result in adding only a few years to the organization’s life.

4 strategies for responding to disruption

If you buy-in to Gans’ argument that predicting and trying to stave off disruption is a fool’s errand, it can be tempting to throw up your hands, declare defeat, and simply wait for disruption to claim your organization as its next victim. And, to be fair, Gans does offer this, Wait and Give up, as one of four possible strategies to deal with disruption.

But let’s say you’re not one to declare defeat easily or quickly, what then?

According to Gans, you first need to acknowledge that the two greatest barriers to innovation are uncertainty and cost. Uncertainty is a barrier because, as described above, you can’t be certain of an innovation’s disruptive path until it is well on the journey and this uncertainty is likely to make managers hesitant to take action. However, even if managers are willing to stomach uncertainty, “established firms face a dilemma in introducing new products or innovations because this cannibalizes their existing, profitable businesses….” This reality, “that there are no free lunches, only trade-offs,” has been part of economic theory since Nobel Prize winner Kenneth Arrow named it “the replacement effect” in a 1962 paper.

For organizations unwilling to surrender to disruption, Gans offers three potential strategies to manage uncertainty and cost and position themselves for success:

1. Double Down by leveraging existing strengths to contain a new entrant. This strategy works best when the innovation to which the organization is responding turns out to NOT be disruptive. In cases where it is disruptive, organizations are likely to face the same challenges and fate as Kodak and Polaroid

2. Wait and Double Up by investing heavily only once it is certain that an innovation is disruptive. This approach works because, as economists Richard Gilbert and David Newbury wrote in 1981, “when an established firm can defend a monopoly segment against innovative entry through investment, its incentive to protect its monopoly will be greater than the incentive for new entrants to invade.”

3. Wait and Buy Up a the most promising new entrant. Even though established firms are likely to pay a premium to acquire the new entrant, it offers them certainty of watching the market shake out and saving them the cost of the Double down or Double up strategies. However, this strategy works the best when only market-side (Christensen) disruption is occurring as “the problem faced by established firms is not the acquisition of such knowledge but instead the integration of different ways of doing things into an organization that already has ingrained processes.”

Putting it all into practice

As much fun as it is to nerd-out on innovation theory, let’s get down to brass tacks and outline what all of this means to Intrapreneurs (people trying to innovate within existing organizations).

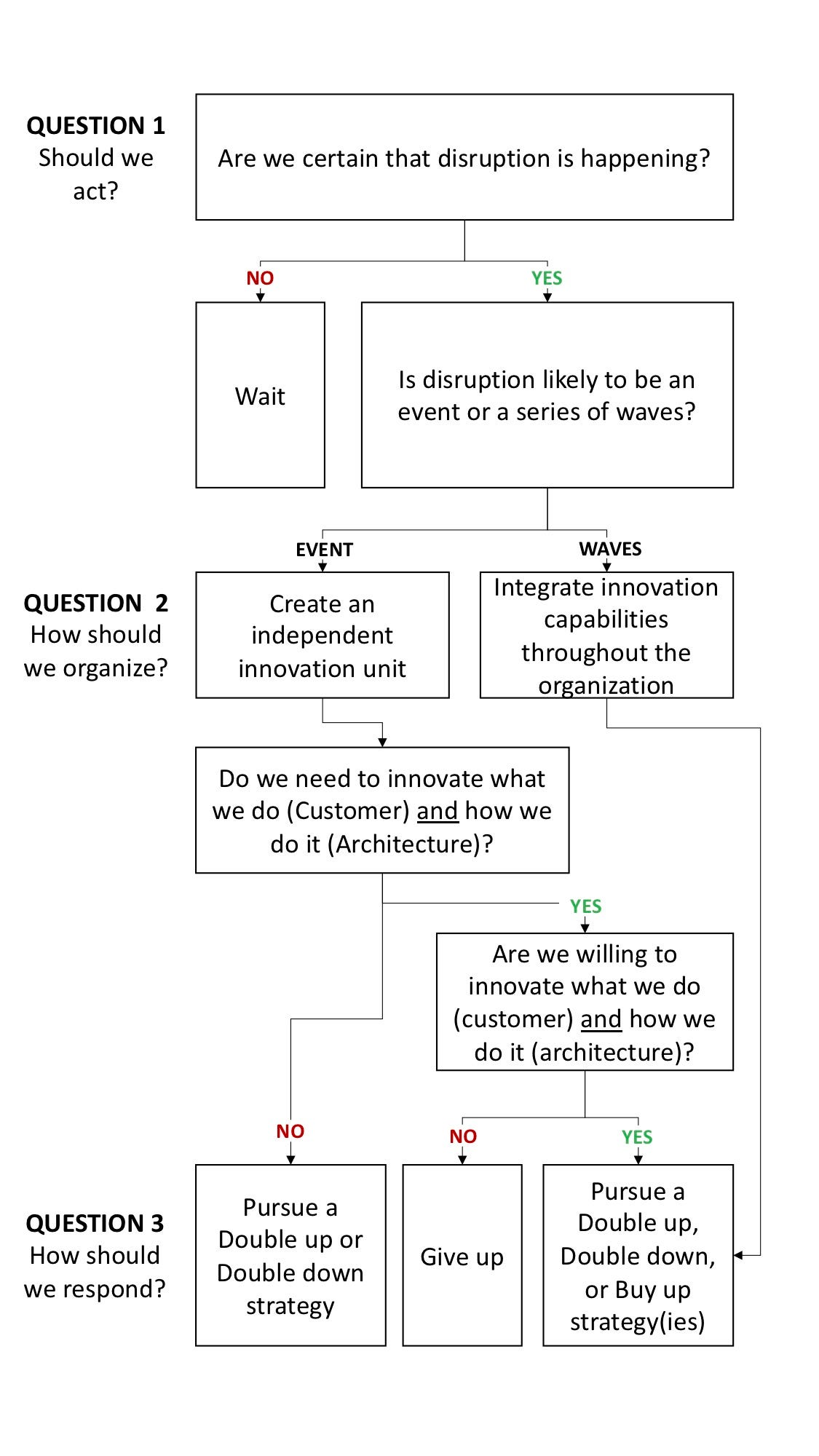

For me, this boils down to three questions organizations need to ask themselves:

1. Should we act in response to a potential disruption?

2. How should we organize to respond?

3. What should we do to respond?

The questions and their corresponding answers form a basic decision tree:

The answers to question 1 were outlined above — large organizations should WAIT until they are certain that disruption is occurring and have confidence in the path it could take

The answers to question 2 reveal another point of difference between Christensen’s and Henderson’s theories:

Christiansen advocates for independent autonomous units, using Lockheed’s famous Skunk Works as an example. He asserts that, in order to be successful, independent units “cannot be forced to compete with projects in the mainstream organization for resources. Because values are the criteria by which prioritization decisions are made, projects that are inconsistent with a company’s mainstream values will naturally be accorded lowest priority. Whether the independent organization is physically separate is less important than is its independence from the normal resource allocation process.” (The Innovator’s Dilemma)

Henderson recommends integration — a culture and practice in which organizations examine and question the implicit linkages in how they operate, evolve them to meet business needs, and readily assimilate linkages that emerge or are acquired. This approach enables firms to respond to both demand- and supply-side disruption. However, “to proactively use integration to prevent disruption often involves sacrificing short-term competitiveness and even market leadership” and, as a result, Gans argued is best used by companies operating in industries where disruption is frequent.

How an organization answers question 3 is based on numerous factors, including available capital, competitive activity, and market/ shareholder pressure. In my experience, however, the choice usually boils down to how the organization has historically grown. Companies that have grown primarily through acquisition should prioritize a Buy up strategy while those that typically grow organically should eschew acquisition for and either Double up or Double Down.

The bottom line

The book wraps up with a nerd-tastic deep dive into Christensen’s research of the micro-processor industry, the data set he used to develop his theory of disruption, and the logic and analysis flaws in his conclusions. It’s worth reading but, as Gans admits, it shouldn’t significantly alter how we think about disruption

Ultimately, by weaving together multiple theories of disruption with tried and true economic theories, The Disruption Dilemma expands how we think and talk about the dynamics that influence if and how organizations respond to disruption and ultimately how we can be more successful when confronting it.