by Robyn Bolton | Dec 10, 2025 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Leading Through Uncertainty

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But what does “safety” look like?

What we say: Safety = Data

We tend to believe that we are rational beings and, as a result, we rely on data to make decisions.

Great! We’ve got lots of data from lots of uncertain periods. HBR examined 4,700 public companies during three global recessions (1980, 1990, and 2000). They found that the companies that the companies that emerged “outperforming rivals in their industry by at least 10% in terms of sales and profits growth” had one thing in common: They aggressively made cuts to improve operational efficiency and ruthlessly invested in marketing, R&D, and building new assets to better serve customers have the highest probability of emerging as markets leaders post-recession.

This research was backed up in 2020 in a McKinsey study that found that “Organizations that maintained their innovation focus through the 2009 financial crisis, for example, emerged stronger, outperforming the market average by more than 30 percent and continuing to deliver accelerated growth over the subsequent three to five years.”

What we do: Safety = Hoarding

The reality is that we are human beings and, as a result, make decisions based on how we feel and the use data to justify those decisions.

How else do you explain that despite the data, only 9% of companies took the balanced approach recommended in the HBR study and, ten years later, only 25% of the companies studied by McKinsey stated that “capturing new growth” was a top priority coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Uncertainty is scary so, as individuals and as organizations, we scramble to secure scarce resources, cut anything that feels extraneous, and shift or focus to survival.

What now? And, not Or.

What was true in 2010 is still true today and new research from Bain offers practical advice for how leaders can follow both their hearts and their heads.

Implement systems to protect you from yourself. Bain studied Fast Company’s 50 Most Innovative Companies and found that 79% use two different operating models for innovation to combat executives’ natural risk aversion. The first, for sustaining innovation uses traditional stage-gate models, seeks input from experts and existing customers, and is evaluated on ROI-driven metrics.

The second, for breakthrough innovations, is designed to embrace and manage uncertainty by learning from new customers and emerging trends, working with speed and agility, engaging non-traditional collaborators, and evaluating projects based on their long-term potential and strategic option value.

Don’t outspend. Out-allocate. Supporting the two-system approach, nearly half of the companies studied send less on R&D than their peers overall and spend it differently: 39% of their R&D budgets to sustaining innovations and 61% to expanding into new categories or business models.

Use AI to accelerate, not create. Companies integrating AI into innovation processes have seen design-to-launch timelines shrink by 20% or more. The key word there is “integrate,” not outsource. They use AI for data and trend analysis, rapid prototyping, and automating repetitive tasks. But they still rely on humans for original thinking, intuition-based decisions, and genuine customer empathy.

Prioritize humans above all else. Even though all the information in the world is at our fingerprints, humans remain unknowable, unpredictable, and wonderfully weird. That’s why successful companies use AI to enhance, not replace, direct engagement with customers. They use synthetic personas as a rehearsal space for brainstorming, designing research, and concept testing. But they also know there is no replacement (yet) for human-to-human interaction, especially when creating new offerings and business models.

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But safety doesn’t guarantee certainty. Nothing does. So, the safest thing we can do is learn from the past, prepare (not plan) for the future, make the best decisions possible based on what we know and feel today, and stay open to changing them tomorrow.

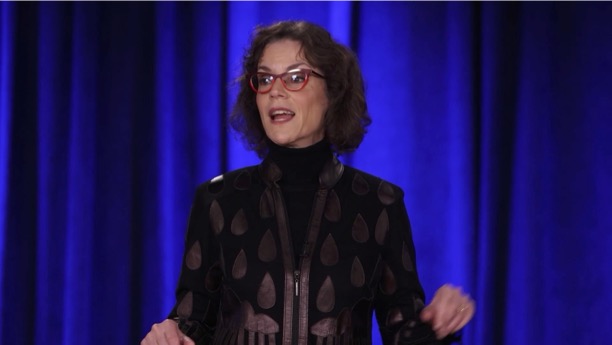

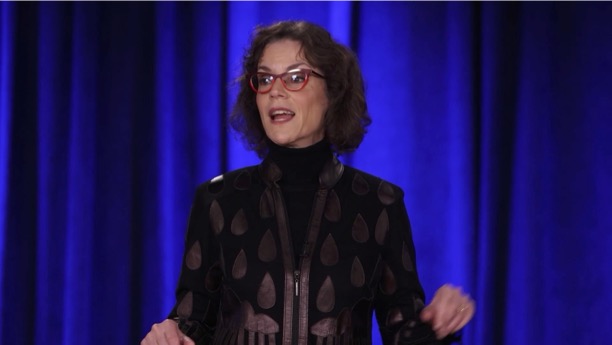

by Robyn Bolton | Oct 6, 2025 | 5 Questions, Customer Centricity, Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

For decades, we’ve faithfully followed innovation’s best practices. The brainstorming workshops, the customer interviews, and the validated frameworks that make innovation feel systematic and professional. Design thinking sessions, check. Lean startup methodology, check. It’s deeply satisfying, like solving a puzzle where all the pieces fit perfectly.

Problem is, we’re solving the wrong puzzle.

As Ellen Di Resta points out in this conversation, all the frameworks we worship, from brainstorming through business model mapping, are business-building tools, not idea creation tools.

Read on to learn why our failure to act on the fundamental distinction between value creation and value capture causes too many disciplined, process-following teams to create beautiful prototypes for products nobody wants.

Robyn: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about innovation that organizations need to unlearn?

Ellen: That the innovation best practices everyone’s obsessed with work for the early stages of innovation.

The early part of the innovation process is all about creating value for the customer. What are their needs? Why are their Jobs to be Done unsatisfied? But very quickly we shift to coming up with an idea, prototyping it, and creating a business plan. We shift to creating value for the business, before we assess whether or not we’ve successfully created value for the customer.

Think about all those innovation best practices. We’ve got business model canvas. That’s about how you create value for the business. Right? We’ve got the incubators, accelerators, lean, lean startup. It’s about creating the startup, which is a business, right? These tools are about creating value for the business, not the customer.

R: You know that Jobs to be Done is a hill I will die on, so I am firmly in the camp that if it doesn’t create value for the customer, it can’t create value for the business. So why do people rush through the process of creating ideas that create customer value?

E: We don’t really teach people how to develop ideas because our culture only values what’s tangible. But an idea is not a tangible thing so it’s hard for people to get their minds around it. What does it mean to work on it? What does it mean to develop it? We need to learn what motivates people’s decision-making.

Prototypes and solutions are much easier to sell to people because you have something tangible that you can show to them, explain, and answer questions about. Then they either say yes or no, and you immediately know if you succeeded or failed.

R: Sounds like it all comes down to how quickly and accurately can I measure outcomes?

E: Exactly. But here’s the rub, they don’t even know they’re rushing because traditional innovation tools give them a sense of progress, even if the progress is wrong.

We’ve all been to a brainstorm session, right? Somebody calls the brainstorm session. Everybody goes. They say any idea is good. Nothing is bad. Come up with wild, crazy ideas. They plaster the walls with 300 ideas, and then everybody leaves, and they feel good and happy and creative, and the poor person who called the brainstorm is stuck.

Now what do they do? They look at these 300 ideas, and they sort them based on things they can measure like how long it’ll take to do or how much money it’ll cost to do it. What happens? They end up choosing the things that we already know how to do! So why have the brainstorm?”

R: This creates a real tension: leadership wants progress they can track, but the early work is inherently unmeasurable. How do you navigate that organizational reality?

E: Those tangible metrics are all about reliability. They make sure you’re doing things right. That you’re doing it the same way every time? And that’s appropriate when you know what you’re doing, know you’re creating value for the customer, and now you’re working to create value for the business. Usually at scale

But the other side of it? That’s where you’re creating new value and you are trying to figure things out. You need validity metrics. Are we doing the right things? How will we know that we’re doing the right things.

R: What’s the most important insight leaders need to understand about early-stage innovation?

E: The one thing that the leader must do is run cover. Their job is to protect the team who’s doing the actual idea development work because that work is fuzzy and doesn’t look like it’s getting anywhere until Ta-Da, it’s done!

They need to strategically communicate and make sure that the leadership hears what they need to hear, so that they know everything is in control, right? And so they’re running cover is the best way to describe it. And if you don’t have that person, it’s really hard to do the idea development work.”

But to do all of that, the leader also must really care about that problem and about understanding the customer.

We must create value for the customer before we can create value for the business. Ellen’s insight that most innovation best practices focus on the latter is devastating. It’s also essential for all the leaders and teams who need results from their innovation investments.

Before your next innovation project touches a single framework, ask yourself Ellen’s fundamental question: “Are we at a stage where we’re creating value for the customer, or the business?” If you can’t answer that clearly, put down the canvas and start having deeper conversations with the people whose problems you think you’re solving.

To learn more about Ellen’s work, check out Pearl Partners.

To dive deeper into Ellen’s though leadership, visit her Substack – Idea Builders Guild.

To break the cycle of using the wrong idea tools, sign-up for her free one-hour workshop.

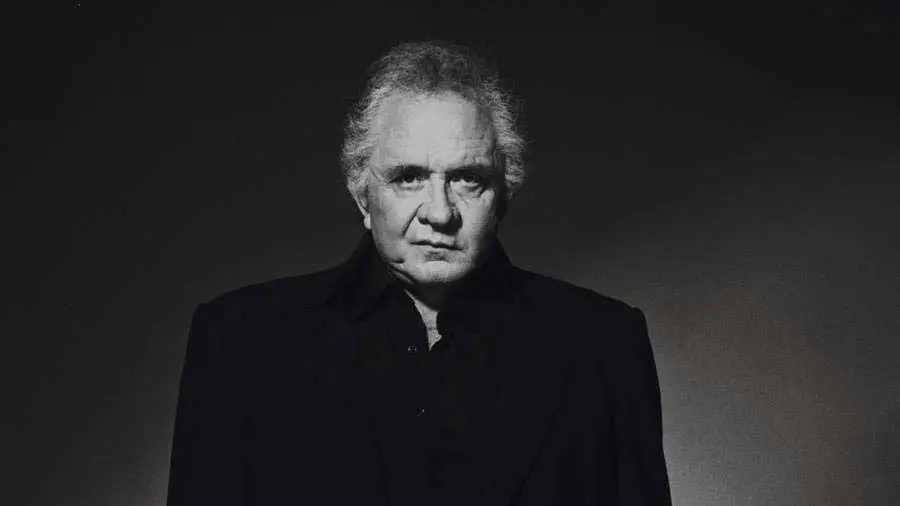

by Robyn Bolton | Aug 4, 2025 | Leadership, Leading Through Uncertainty, Stories & Examples, Strategy

The best business advice can destroy your business. Especially when you follow it perfectly.

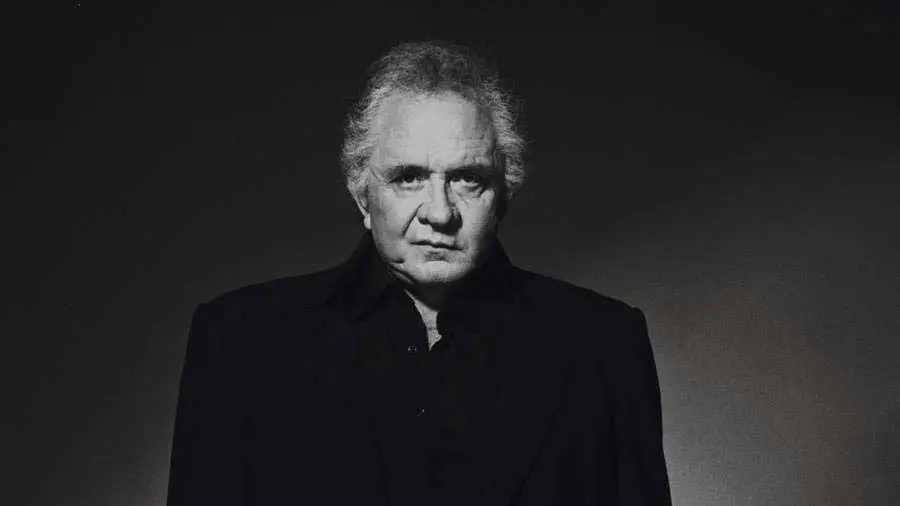

Just ask Johnny Cash.

After bursting onto the scene in the mid-1950s with “Folsom Prison Blues”, Cash enjoyed twenty years of tremendous success. By the 1970s, his authentic, minimalist approach had fallen out of favor.

Eager to sell records, he pivoted to songs backed by lush string arrangements, then to “country pop” to attract mainstream audiences and feed the relentless appetite of 900 radio stations programming country pop full-time.

By late 1992, Johnny Cash’s career was roadkill. Country radio had stopped playing his records, and Columbia Records, his home for 25 years, had shown him the door. At 60, he was marooned in faded casinos, playing to crowds preferring slot machines to songs.

Then he took the stage at Madison Square Garden for Bob Dylan’s 30th anniversary concert.

In the audience sat Rick Rubin, co-founder of Def Jam Recordings and uber producer behind Public Enemy, Run-DMC, and Slayer, amongst others. He watched in awe as Cash performed, seeing not a relic but raw power diluted by smart decisions.

The Stare-Down that Saved a Career

Four months later, Rubin attended Cash’s concert at The Rhythm Café in Santa Anna, California. According to Cash’s son, “When they sat down at the table, they said: ‘Hello.’ But then my dad and Rick just sat there and stared at each other for about two minutes without saying anything, as if they were sizing each other up.”

Eventually, Cash broke the silence, “What’re you gonna do with me that nobody else has done to sell records for me?”

What happened next resurrected his career.

Rubin didn’t promise record sales. He promised something more valuable: creative control and a return to Cash’s roots.

Ten years later, Cash had a Grammy, his first gold record in thirty years, and CMA Single of the Year for his cover of Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt,” and millions in record sales.

When Smart Decisions Become Fatal

Executives do exactly what Cash did. You respond to market signals. You pivot your offering when customer preferences shift and invest in emerging technologies.

All logical. All defensible to your board. All potentially fatal.

Because you risk losing what made you unique and valuable. Just as Cash lost his minimalist authenticity and became a casualty of his effort to stay relevant, your business risks losing sight of its purpose and unique value proposition.

Three Beliefs at the Core of a Comeback

So how do you avoid Cash’s initial mistake while replicating his comeback? The difference lies in three beliefs that determine whether you’ll have the creative courage to double down on what makes you valuable instead of diluting it.

- Creative confidence: The belief we can think and act creatively in this moment.

- Perceived value of creativity: Our perceived value of thinking and acting in new ways.

- Creative risk-taking: The willingness to take the risks necessary for active change.

Cash wanted to sell records, and he:

- Believed that he was capable of creativity and change.

- Saw the financial and reputational value of change

- Was willing to partner with a producer who refused to guarantee record sales but promised creative control and a return to his roots.

Your Answers Determine Your Outcome

Like Cash, what you, your team, and your organization believe determines how you respond to change:

- Do I/we believe we can creatively solve this specific challenge we’re facing right now?

- Is finding a genuinely new approach to this situation worth the effort versus sticking with proven methods?

- Am I/we willing to accept the risks of pursuing a creative solution to our current challenge?”

Where there are “no’s,” there is resistance, even refusal, to change. Acknowledge it. Address it. Do the hard work of turning the No into a Yes because it’s the only way change will happen.

The Comeback Question

Cash proved that authentic change—not frantic pivoting—resurrects careers and disrupts industries. His partnership with Rubin succeeded because he answered “yes” to all three creative beliefs when it mattered most. Where are your “no’s” blocking your comeback?

by Robyn Bolton | Jun 25, 2025 | Leadership, Stories & Examples, Strategy

Convinced that Strategic Foresight shows you a path through uncertainty? Great! Just don’t rush off, hire futurists, run some workshops, and start churning out glossy reports.

Activity is not achievement.

Learning from those who have achieved, however, is an excellent first activity. Following are the stories of two very different companies from different industries and eras that pursued Strategic Foresight differently yet succeeded because they tied foresight to the P&L.

Shell: From Laggard to Leader, One Decision at a Time

It’s hard to imagine Shell wasn’t always dominant, but back in the 1960s, it struggled to compete. Tired of being blindsided by competitors and external events, they sought an edge.

It took multiple attempts and more than 10 years to find it.

In 1959, Shell set up their Group Planning department, but its reliance on simple extrapolations of past trends to predict the future only perpetuated the status quo.

In 1965, Shell introduced the Unified Planning Machinery, a computerized forecasting tool to predict cash flow based on current results and forecasted changes in oil consumption. But this approach was abandoned because executives feared “that it would suppress discussion rather than encourage debate on differing perspectives.”

Then, in 1967, in a small 18th-floor office in London, a new approach to ongoing planning began. Unlike past attempts, the goal was not to predict the future. It was to “modify the mental model of decision-makers faced with an uncertain future.”

Within a few years, their success was obvious. Shell executives stopped treating scenarios as interesting intellectual exercises and started using them to stress-test actual capital allocation decisions.

This doesn’t mean they wholeheartedly embraced or even believed the scenarios. In fact, when scenarios suggested that oil prices could spike dramatically, most executives thought it was far-fetched. Yet Shell leadership used those scenarios to restructure their entire portfolio around different types of oil and to develop new capabilities.

The result? When the 1973 oil crisis hit and oil prices quadrupled from $2.90 to $11.65 per barrel, Shell was the only major oil company ready. While competitors scrambled and lost billions, Shell turned the crisis into “big profits.”

Disney: From Missed Growth Goals to Unprecedented Growth

In 2012, Walt Disney International’s (WDI) aggressive growth targets collided with a challenging global labor market, and traditional HR approaches weren’t cutting it.

Andy Bird, Chairman of Walt Disney International, emphasized the criticality of the situation when he said, “The actions we make today are going to make an impact 10 to 20 years down the road.”

So, faced with an unprecedented challenge, the team pursued an unprecedented solution: they built a Strategic Foresight capability.

WDI trained over 500 leaders across 45 countries, representing five percent of its workforce, in Strategic Foresight. More importantly, Disney integrated strategic foresight directly into their strategic planning and performance management processes, ensuring insights drove business decisions rather than gathering dust in reports.

For example, foresight teams identified that traditional media consumption was fracturing (remember, this was 2012) and that consumers wanted more control over when and how they consumed content. This insight directly shaped Disney+’s development.

The results speak volumes. While traditional media companies struggled with streaming disruption, Disney+ reached 100 million subscribers in just 16 months.

Two Paths. One Result.

Shell and Disney integrated Strategic Foresight differently – the former as a tool to make high-stakes individual decisions, the latter as an organizational capability to affect daily decisions and culture.

What they have in common is that they made tomorrow’s possibilities accountable to today’s decisions. They did this not by treating strategic foresight as prediction, but as preparation for competitive advantage.

Ready to turn these insights into action? Next week, we’ll dive into the tools in the Strategic Foresight toolbox and how you and your team can use them to develop strategic foresight that drives informed decisions.

by Robyn Bolton | May 30, 2025 | Leadership, Strategy

Conventional wisdom tells us that transformation flows from the C-suite down because real change requires executive mandates and company-wide rollouts. But what if our focus on building transformation momentum is exactly backward?

Ever since reading Multipliers, where Liz Wiseman revealed how the best leaders amplify their people rather than diminish them, I’ve wondered if, like innovation, organizational transformation and change also require us to do the opposite of our instincts.

I recently had the opportunity to dig deeper into this topic with her, and I couldn’t resist exploring how change really happens in large organizations.

What emerged wasn’t another framework—it was something more brilliant and subversive: how middle managers quietly become change agents, why sustainable transformation looks nothing like a launch event, and the liberating truth that leaders don’t need to be perfect.

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about leading change that you believe organizations need to unlearn?

Lize Wiseman: I don’t believe that change needs to start, or even be sponsored, at the top of the organization. I’ve seen so much change led from the middle management ranks. When middle managers experiment with new mindsets and practices inside their organizations, they produce pockets of success—anomalies that catch the attention of senior executives and corporate staffers who are highly adept at detecting variances (both negative and positive). When senior executives notice positive outcomes, they are quick to elevate and endorse the new practices, in turn spreading the practices to other parts of the organization. In other words, most senior executives are adept at spotting a parade and getting in front of it! (Incidentally, this is one of several executive skills you won’t find documented on any official leadership competency model.) If you don’t yet have the political capital to lead a company-wide initiative, run a pilot with a few rising middle managers. Shine a spotlight on their success and let the practices spread to their peers. Expose their good work to the executive team and make yourself available to turn the parade into a movement.

RB: In your research and work, what’s the most surprising pattern you’ve observed about successful organizational transformation?”

LW: As mentioned above, I believe the starting point for transformation is less important than how you will sustain the momentum you’ve generated. Unfortunately, most new initiatives—be they corporate change initiatives or personal improvement plans—begin with a bang but fizzle out in what I call “the failure to launch” cycle. Transformation that is sustained over time usually starts small and builds a series of successive wins. Each win provides the energy needed to carry the work into the next phase. These series of wins generate the energy and collective will needed to complete the cycle of success. As that cycle spins, nascent beliefs become more deeply entrenched and old survival strategies get supplanted by new methods to not just survive but thrive inside the organization.

Each little success requires careful support and an evidence-backed PR campaign to build awareness and broad support for the new direction. Nascent behavior and beliefs are fragile and will be overpowered by older assumptions until they are strengthened by supporting evidence. The supporting evidence forms a buttress around the budding mindset or practices, much like a brace around a sapling provides stability until the tree is strong enough to stand on its own.

RB: How has your thinking about what makes an effective leader evolved over the course of your career?

LW: When I began researching good leadership, most diminishing leaders appeared to be tyrannical, narcissistic bullies. But as I further studied the problem, I’ve come to see that the vast majority of the diminishing happening inside our workplaces is done with the best of intentions, by what I call the Accidental Diminisher—good people trying to be good managers. I’ve become less interested in knowing who is a Diminisher and much more interested in understanding what provokes the Diminisher tendencies that lurk inside each of us.

RB: When you consider all the organizations you’ve studied, what’s the most powerful lesson about driving meaningful change that most leaders overlook?

LW: One of the dangers of trying to lead change from the top is that most leaders have a hard time being a constant role model for the changes they advocate for. Even the best leaders can’t always display the positive behaviors they espouse and ask their organizations to embody. It’s human to slip up. But when behavior change is led primarily from the top, these all-too-natural slip-ups can become major setbacks for the whole organization because they provide visible evidence that the new behavior isn’t required or feasible, and followers can easily give up. Wise leaders understand this dynamic and build a hypocrisy factor into their change plans–meaning, they acknowledge upfront that they aspire to the new behavior but don’t always fully embody it, yet. They set the expectation that there will be setbacks and invite people to help them be better leaders as well. They acknowledge that the route to new behavior typically looks like the acclimation process used by high-elevation climbers. These climbers spend some of their days in ascent, but once they reach new elevations, often have to descend to lower camps to acclimate. It’s the proverbial two-steps-forward, one-step-back process. When leaders acknowledge their shortcomings and the likelihood of their future missteps, they not only minimize the chance that others give up when they see hypocrisy above them, but they create space for others to make and recover from their own mistakes.

RB: Looking ahead, what do you believe is the most important capability leaders need to develop to help their organizations thrive?

LW: Leading in uncertainty, specifically the ability to lead people to destinations that they themselves have never been.

I love that Liz’s insights flip the script, calling on people outside the C-Suite to stop waiting for permission and start running quiet experiments, building proof points, and letting success do the selling.

The next time you want a change or have change thrust upon you, don’t look for a parade to lead. Look for one person willing to try something different and get to work.