by Robyn Bolton | Aug 20, 2025 | AI, Metrics

Sometimes, you see a headline and just have to shake your head. Sometimes, you see a bunch of headlines and need to scream into a pillow. This week’s headlines on AI ROI were the latter:

- Companies are Pouring Billions Into A.I. It Has Yet to Pay Off – NYT

- MIT report: 95% of generative AI pilots at companies are failing – Forbes

- Nearly 8 in 10 companies report using gen AI – yet just as many report no significant bottom-line impact – McKinsey

AI has slipped into what Gartner calls the Trough of Disillusionment. But, for people working on pilots, it might as well be the Pit of Despair because executives are beginning to declare AI a fad and deny ever having fallen victim to its siren song.

Because they’re listening to the NYT, Forbes, and McKinsey.

And they’re wrong.

ROI Reality Check

In 20205, private investment in generative AI is expected to increase 94% to an estimated $62 billion. When you’re throwing that kind of money around, it’s natural to expect ROI ASAP.

But is it realistic?

Let’s assume Gen AI “started” (became sufficiently available to set buyer expectations and warrant allocating resources to) in late 2022/early 2023. That means that we’re expecting ROI within 2 years.

That’s not realistic. It’s delusional.

ERP systems “started” in the early 1990s, yet providers like SAP still recommend five-year ROI timeframes. Cloud Computing“started” in the early 2000s, and yet, in 2025, “48% of CEOs lack confidence in their ability to measure cloud ROI.” CRM systems’ claims of 1-3 years to ROI must be considered in the context of their 50-70% implementation failure rate.

That’s not to say we shouldn’t expect rapid results. We just need to set realistic expectations around results and timing.

Measure ROI by Speed and Magnitude of Learning

In the early days of any new technology or initiative, we don’t know what we don’t know. It takes time to experiment and learn our way to meaningful and sustainable financial ROI. And the learnings are coming fast and furious:

Trust, not tech, is your biggest challenge: MIT research across 9,000+ workers shows automation success depends more on whether your team feels valued and believes you’re invested in their growth than which AI platform you choose.

Workers who experience AI’s benefits first-hand are more likely to champion automation than those told, “trust us, you’ll love it.” Job satisfaction emerged as the second strongest indicator of technology acceptance, followed by feeling valued. If you don’t invest in earning your people’s trust, don’t invest in shiny new tech.

More users don’t lead to more impact: Companies assume that making AI available to everyone guarantees ROI. Yet of the 70% of Fortune 500 companies deploying Microsoft 365 Copilot and similar “horizontal” tools (enterprise-wide copilots and chatbots), none have seen any financial impact.

The opposite approach of deploying “vertical” function-specific tools doesn’t fare much better. In fact, less than 10% make it past the pilot stage, despite having higher potential for economic impact.

Better results require reinvention, not optimization: McKinsey found that call centers that gave agents access to passive AI tools for finding articles, summarizing tickets, and drafting emails resulted in only a 5-10% call time reduction. Centers using AI tools to automate tasks without agent initiation reduced call time by 20-40%.

Centers reinventing processes around AI agents? 60-90% reduction in call time, with 80% automatically resolved.

How to Climb Out of the Pit

Make no mistake, despite these learnings, we are in the pit of AI despair. 42% of companies are abandoning their AI initiatives. That’s up from 17% just a year ago.

But we can escape if we set the right expectations and measure ROI on learning speed and quality.

Because the real concern isn’t AI’s lack of ROI today. It’s whether you’re willing to invest in the learning process long enough to be successful tomorrow.

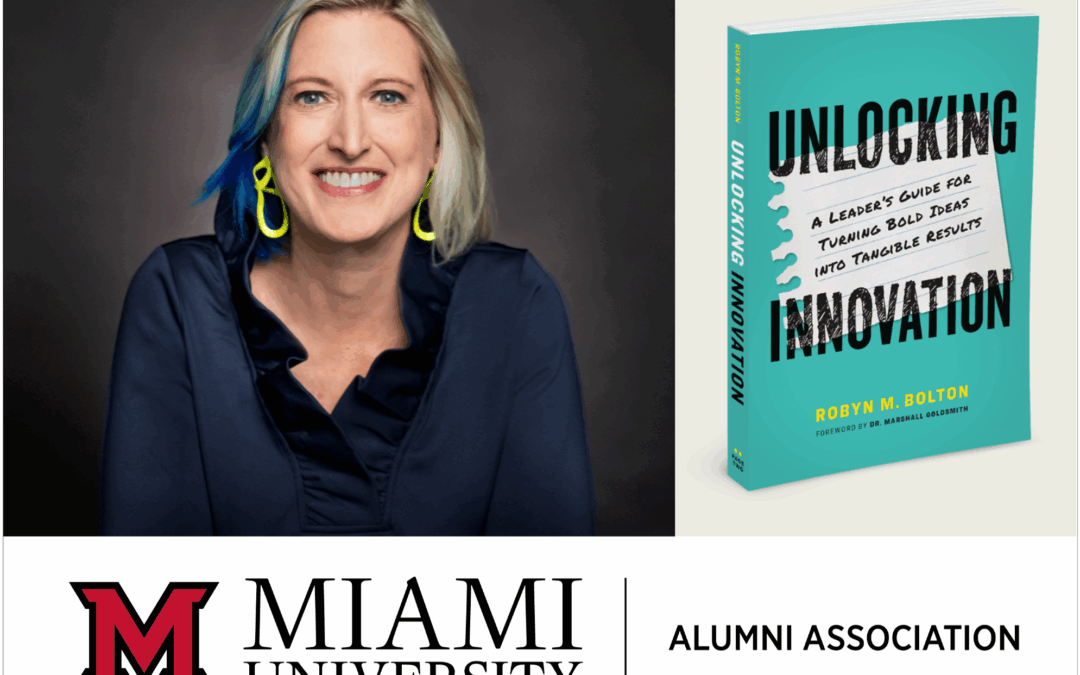

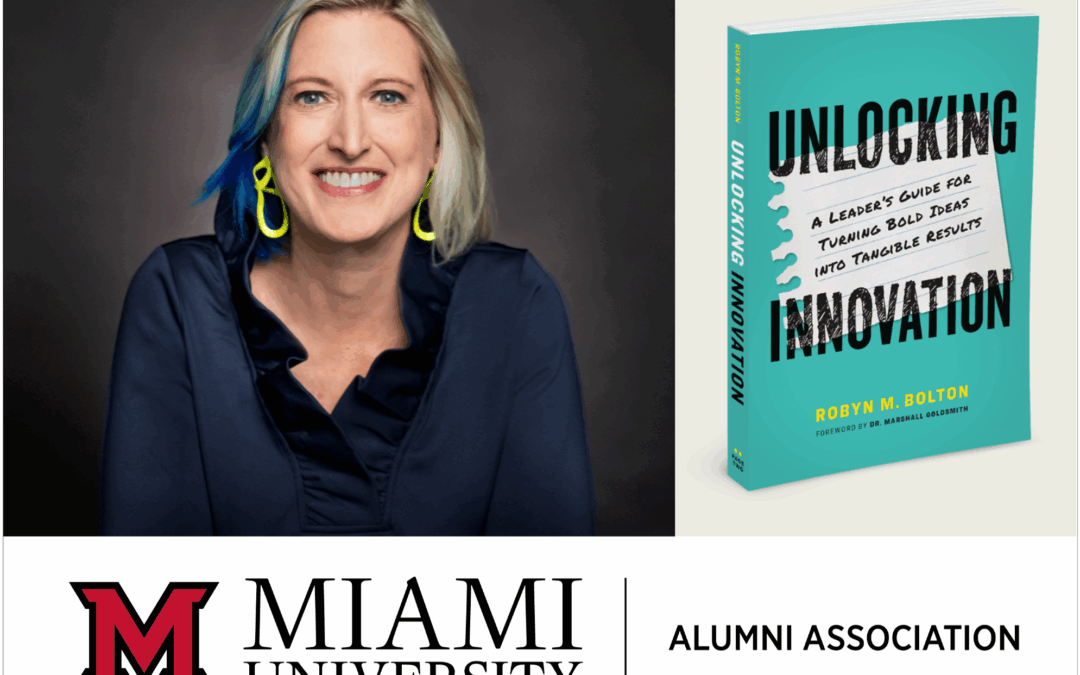

by Robyn Bolton | Aug 13, 2025 | Speaking

by Robyn Bolton | Aug 4, 2025 | Leadership, Leading Through Uncertainty, Stories & Examples, Strategy

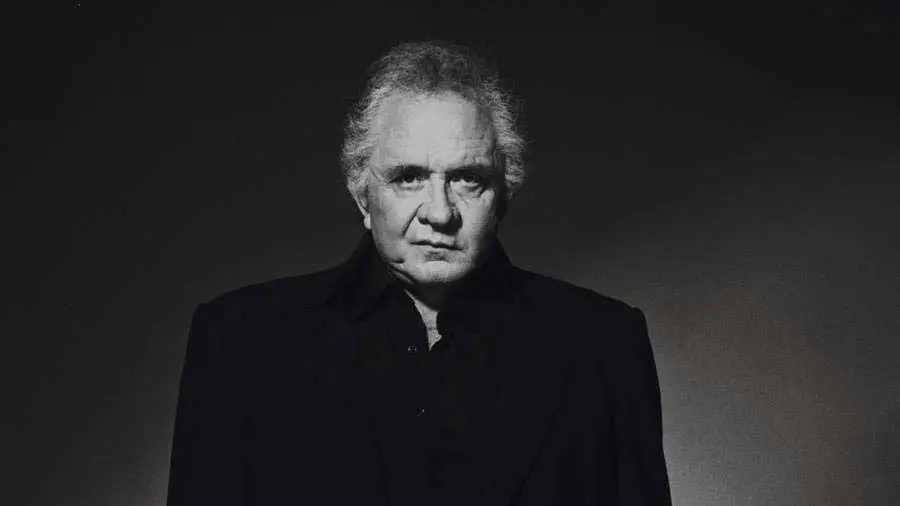

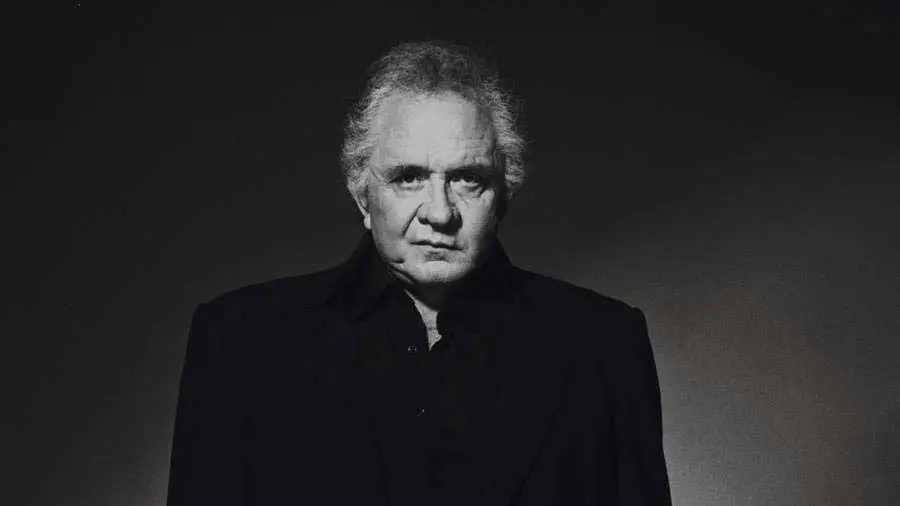

The best business advice can destroy your business. Especially when you follow it perfectly.

Just ask Johnny Cash.

After bursting onto the scene in the mid-1950s with “Folsom Prison Blues”, Cash enjoyed twenty years of tremendous success. By the 1970s, his authentic, minimalist approach had fallen out of favor.

Eager to sell records, he pivoted to songs backed by lush string arrangements, then to “country pop” to attract mainstream audiences and feed the relentless appetite of 900 radio stations programming country pop full-time.

By late 1992, Johnny Cash’s career was roadkill. Country radio had stopped playing his records, and Columbia Records, his home for 25 years, had shown him the door. At 60, he was marooned in faded casinos, playing to crowds preferring slot machines to songs.

Then he took the stage at Madison Square Garden for Bob Dylan’s 30th anniversary concert.

In the audience sat Rick Rubin, co-founder of Def Jam Recordings and uber producer behind Public Enemy, Run-DMC, and Slayer, amongst others. He watched in awe as Cash performed, seeing not a relic but raw power diluted by smart decisions.

The Stare-Down that Saved a Career

Four months later, Rubin attended Cash’s concert at The Rhythm Café in Santa Anna, California. According to Cash’s son, “When they sat down at the table, they said: ‘Hello.’ But then my dad and Rick just sat there and stared at each other for about two minutes without saying anything, as if they were sizing each other up.”

Eventually, Cash broke the silence, “What’re you gonna do with me that nobody else has done to sell records for me?”

What happened next resurrected his career.

Rubin didn’t promise record sales. He promised something more valuable: creative control and a return to Cash’s roots.

Ten years later, Cash had a Grammy, his first gold record in thirty years, and CMA Single of the Year for his cover of Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt,” and millions in record sales.

When Smart Decisions Become Fatal

Executives do exactly what Cash did. You respond to market signals. You pivot your offering when customer preferences shift and invest in emerging technologies.

All logical. All defensible to your board. All potentially fatal.

Because you risk losing what made you unique and valuable. Just as Cash lost his minimalist authenticity and became a casualty of his effort to stay relevant, your business risks losing sight of its purpose and unique value proposition.

Three Beliefs at the Core of a Comeback

So how do you avoid Cash’s initial mistake while replicating his comeback? The difference lies in three beliefs that determine whether you’ll have the creative courage to double down on what makes you valuable instead of diluting it.

- Creative confidence: The belief we can think and act creatively in this moment.

- Perceived value of creativity: Our perceived value of thinking and acting in new ways.

- Creative risk-taking: The willingness to take the risks necessary for active change.

Cash wanted to sell records, and he:

- Believed that he was capable of creativity and change.

- Saw the financial and reputational value of change

- Was willing to partner with a producer who refused to guarantee record sales but promised creative control and a return to his roots.

Your Answers Determine Your Outcome

Like Cash, what you, your team, and your organization believe determines how you respond to change:

- Do I/we believe we can creatively solve this specific challenge we’re facing right now?

- Is finding a genuinely new approach to this situation worth the effort versus sticking with proven methods?

- Am I/we willing to accept the risks of pursuing a creative solution to our current challenge?”

Where there are “no’s,” there is resistance, even refusal, to change. Acknowledge it. Address it. Do the hard work of turning the No into a Yes because it’s the only way change will happen.

The Comeback Question

Cash proved that authentic change—not frantic pivoting—resurrects careers and disrupts industries. His partnership with Rubin succeeded because he answered “yes” to all three creative beliefs when it mattered most. Where are your “no’s” blocking your comeback?

by Robyn Bolton | Jul 29, 2025 | Podcasts

by Robyn Bolton | Jul 28, 2025 | 5 Questions, Leadership

Picture this: your boss announces a major reorganization with a big smile, expecting you to be excited about “new opportunities.” Meanwhile, you’re sitting there thinking “What the hell just happened to my job?”

Theresa Ward, founder and Chief Momentum Officer of Fiery Feather, has spent years watching this disconnect play out. Her insight? Leaders are expected to sell change while still personally struggling with it, creating what she calls “that weird middle ground” where authenticity goes to die.

Our conversation revealed why unwelcome change triggers the same response as grief, and why leaders who stop pretending they’ve got it figured out are more successful.

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about leading change that organizations need to unlearn?

Theresa Ward: That middle managers need to be enthusiastic about a change, or at least appear enthusiastic, to lead their teams through it.

RB: It seems like enthusiasm is important to get people on board and doing what they need to do to make change happen. Why is this wrong?

TW: Because it makes you wonder if this person is being authentic. Are they genuinely enthusiastic? Do they really believe this is the right thing?

To be clear, I’m talking about Unwelcome Change. Change that is thrust upon you. How we experience Unwelcome Change is the same way we experience grief.

When we initially experience Unwelcome Change, our brain goes into shock or denial which can actually trigger an increase in engagement and productivity.

Then we move into anger and blame, which looks different for all of us. We’ve probably experienced somebody yelling in a meeting, but it can also look like turning off the camera, folding your arms, rolling your eyes, and disengaging.

Bargaining. I always think of that clip from Jerry Maguire, where he’s got the goldfish, and he says, “Who’s coming with me?” because he’s going to make lemonades out of this lemon, even if it’s a completely ridiculous condition.

Then depression sets in. It’s the low point but it’s also where you’re really ready to admit that you’re upset, sad, and grieving the change that has happened. It’s the dark before the dawn.

RB: If everyone goes through this grief process, why do some leaders seem genuinely enthusiastic about the change?”

TW: If they came up with the idea, they’re not going to be angry or depressed about their own idea.

But even if it’s one announcement, people don’t experience just one change. It’s not, “Our budget is going from X to Y” and everyone can just get used to it. It’s double or triple that! It’s a budget cut, then a reorg, then a new boss, then a friend being laid off, then a project you loved getting trashed. You’re dealing with onion layers of change.

We all go through different stages at speeds. You can’t rush it. Sometimes you just have to be like, “Oh, okay, I’m feeling pretty angry this week. I’m just gonna have to sit through my anger phase and realize that it’s a phase.”

RB: I get that you can’t rush the process, but change doesn’t slow down so you can catch up. What can people do to navigate change while they’re processing it?

TW: BLT, baby. These are 3 tools, not a formula, that you can use for different experiences.

B stands for Benefit of Change. This is finding the silver lining, something we often underestimate because it’s such a broad cliche. For it to be effective, you need to look for a specific and personal silver lining. For example, a friend of mine works for a company that was acquired. He was not a fan of how the culture was changing, but the bigger company offered tuition reimbursement. So he used that to get his master’s of fine arts for free.

L is Locus of Control. Take inventory of everything that’s upsetting you and place it into one of 3 categories: What can I control? What can I influence? What do I need to just surrender? Sitting up at night and worrying about whether the budget will be cut again is outside of my control. So, I shouldn’t spend my time and energy on that. Instead, I need to focus on what I can control, like my attitude and response.

T is Take the Long View. Every day we find ourselves in situations that get us emotional – a traffic jam, getting cut off in traffic, or flubbing a big client presentation. When we get more emotional than what the situation calls for, ask how you’re going to feel about the situation tomorrow, then in a month, then a year Because when our fight or flight brain mode kicks in, we catastrophize things. But the reality is that most of it won’t matter tomorrow.

RB: What’s the most important mindset shift leaders need to make to help their teams through unwelcome change?

TW: Find what works for you first then, with empathy, help your team. Like the Airline Safety Video, put your mask on first, then help others. It allows you to be authentic and builds empathy with the team. Two things required to start the shift from unwelcome to accepted.

Theresa’s BLT framework won’t make change painless, but it gives you permission to admit that transformation is hard, even for leaders. The moment you stop pretending you’ve got it all figured out is the moment your team starts trusting you to guide them through the mess.